The first of November marks All Saints Day on many church calendars—a day when we Christians remember our martyrs together with all the faithful, both living and departed. On that day, we celebrate that our communion is not simply with one another on earth but is also with all saints of all time, including those who have died.

For some people, the notion of fellowship with departed saints might be quite exciting. They may have pondered questions about the saints since school assemblies or RE lessons. What was racing through Abraham’s mind when he attempted to sacrifice his son Isaac? What would Mary say a sinless Jesus was like as a toddler? Did Jonah float around inside the great fish, or did he find something on which to perch himself?

But others among us might wish to skip All Saints Day altogether. Talk of dead saints feels positively medieval, even a bit morbid. Some of us might wonder about our own saintliness—or lack thereof. Could we really experience ineffable joy in an afterlife? Moreover, the very suggestion of an afterlife implies that we ourselves must die—an uncomfortable prospect for most of us.

Such divergent reactions to the day are revealing. On the one hand, the idea of having saints to remember is to inspire us to live well. They invite us to examine their lives and to grow ourselves in response. On the other hand, they remind us that our days are numbered. And because our days are numbered, we should attend carefully to what it means to live wisely. Saints teach us that if we want to die well, we must live well.

But living well in order to die well doesn’t simply happen. It takes work. It takes preparation. Which is why this year on All Saints Day it’s worth asking the question: Am I prepared for death?

Death exists as a paradox for Christians—as something at once lurking and vanquished.

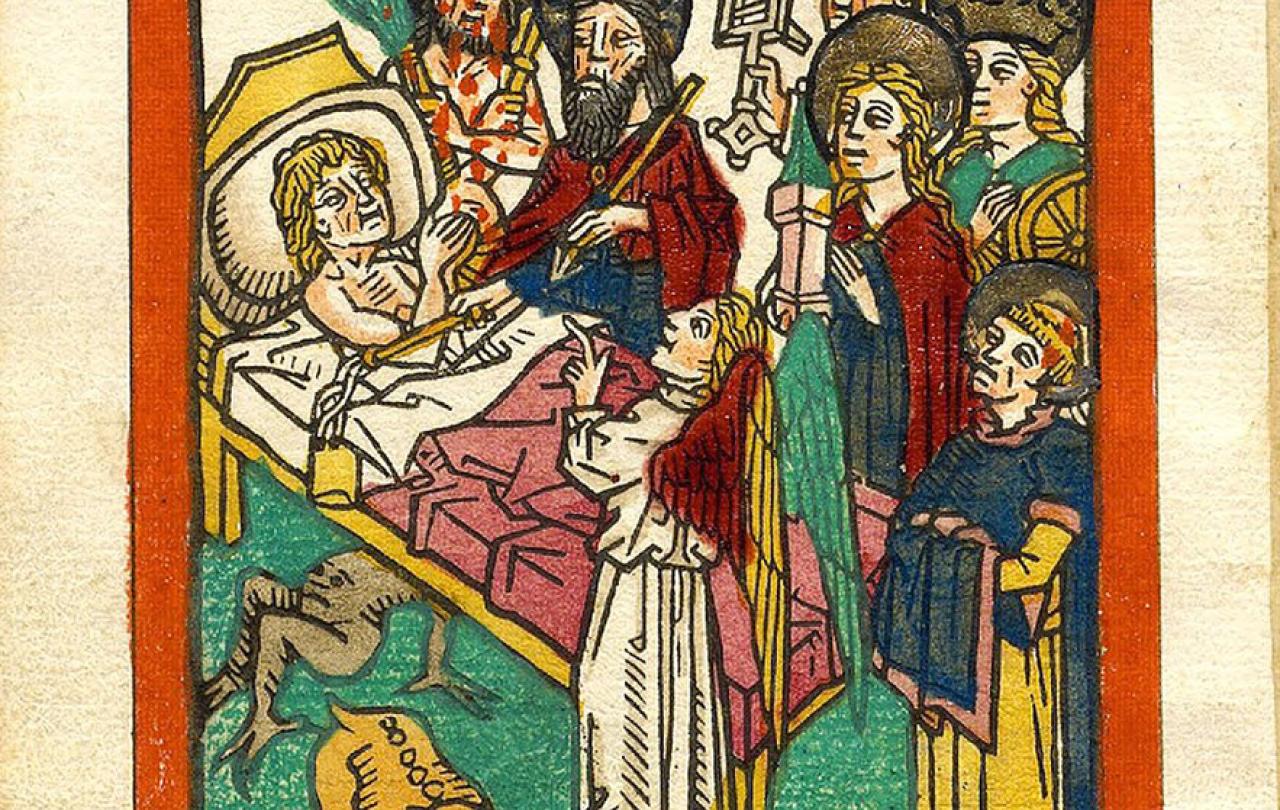

In the late Middle Ages, the ars moriendi, or ‘art of dying’ genre of literature developed in response to mass loss of life from a fourteenth-century outbreak of bubonic plague. The genre consisted of a number of handbooks on how to prepare for death. Although the earliest text was anonymous, historians believe that its authorship had a connection to the Western Church. After the Reformation, Protestant versions began to circulate, and later handbooks omitted religious particularity altogether. The handbooks grew in popularity throughout the West for more than 500 years.

This notion of living well to die well lay at the core of the various iterations of the ars moriendi. Early texts warned readers that five temptations lead to dying poorly—temptations to doubt, despair, impatience, greed, and pride. If you don’t want to die a doubting, despairing, impatient, greedy, and proud person, you must cultivate the virtues of faith, hope, patience, generosity, and humility now. But the ars moriendi texts were very clear that virtue did not happen to a person all at once at the end of life. Rather, it required habituation. Cultivating virtues was the work of a lifetime. If you want to be remembered as a person of sound character, a generous person of hope and good will toward others, you cannot delay making such attributes a regular practice. If you are willing to be martyred for your faith—as some of those early saints were—you have got to be sure it is a faith worth dying for.

I once met a man who had converted from the religion of radical self-centeredness to Christianity. When I asked him why, he told me that of all the world’s religions, Christianity had the best story. As with the martyred saints, it was for him a story worth dying for. And All Saints Day reminds us that in Christianity, death is stranger than you might think.

Death exists as a paradox for Christians—as something at once lurking and vanquished. Death is the enemy that at long last will be destroyed, and death has already been swallowed up in victory. But you might ask: if death has already been defeated, what remains to be destroyed? And if death will be destroyed, how has it then been defeated? This enigma might partially explain why many regular church attenders are neither physically nor spiritually prepared for death. Researchers at Harvard University have shown that people who describe themselves as most supported by their religious communities are also most likely to reject hospice care and instead to elect aggressive life-extending technology.

The story goes as follows. Death is an enemy because it suggests rejection of God. From the beginning, God tells our forebearer Adam that he can freely eat of any tree in the garden but one. If he eats from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, he will die. Thus, from the beginning, God equates the possibility of human disobedience with the actuality of death.

Of course, Adam and Eve eat the proverbial apple. And when they do, they don’t immediately die, but they experience a sort of death. For the first time, they become filled with shame and fear. They hide themselves from God. They cast blame. God tells them that moving forward their life will be filled with great suffering. God says to Adam, ‘By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken. You are dust, and to dust you shall return.’ Disobedience is what Christians call ‘sin’—and it brings death. Sin severs that once harmonious relationship between God and people—a fact that also grieves God, which is why God does not let death have the final word.

The story gets better. Since we humans cannot possibly undo the drastic results of our disobedience, God becomes fully human in Jesus Christ, so liable to death, while also retaining full, divinity which cannot die. Then, as a human on a cross, he dies as the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of humankind. But this God-Man does not stay dead. After three days in the tomb, Christ is resurrected, defeating death, on what has come to be known as Easter Sunday. Christ’s resurrection functions as a sort of guarantee that all God’s people will one day be resurrected and receive new bodies, that day on which the great enemy of death will be destroyed once and for all. If Adam and Eve brought death into the world, the resurrection hope is that death will be no more.

This year on All Saints Day we have the opportunity to consider what it means to commune with ‘all saints’ extending back to Adam and forward to future generations. We have the opportunity to study the saints and then examine ourselves. What sort of people are we becoming? Are we living well to die well, as the ars moriendi handbooks teach? And of all the stories out there, which provides the greatest hope in life and in death?