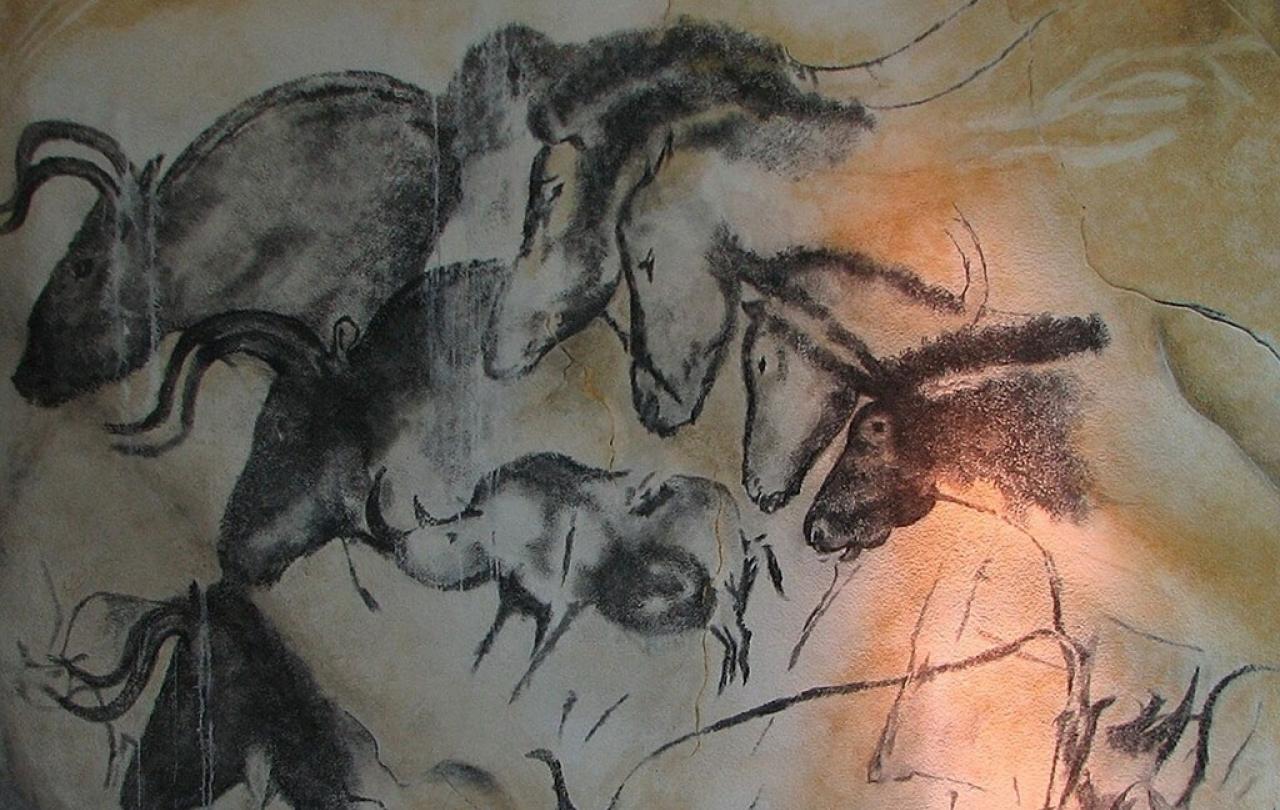

Late on a winter’s afternoon in December 1994, a group of three French cavers received the kind of Christmas present that most spelunkers can only dream of. They were exploring a cave system that they had just discovered in a deep gorge in southeastern France, and were already delighted by some of the natural geological formations that they’d seen. Suddenly they emerged into a large cavern and found themselves standing in front of a series of wall paintings that took their breath away. In the feeble beams of light from their torches the three explorers were stunned to see huge painted panels swarming with vibrant, beautifully crafted images of animals, including species like mammoths, lions and rhinoceros that had long been extinct in Europe.

The only way in and out of the cavern was through a series of narrow passageways and shafts. So, these experienced explorers understood immediately that the paintings must have been created in the Stone Age and that they were probably the first people in tens of thousands of years to see them. They had made a spectacular archaeological discovery and Chauvet Cave - named after the group’s leader, Jean-Marie Chauvet - quickly took its place alongside Altamira and Lascaux as one of the most important sites of prehistoric art.

Although the cavers were very much aware of the historical and scientific value of their discovery, what really overwhelmed them was the nature and quality of the images. In their book, The Chauvet Cave: The Oldest Known Paintings in the World (London: 1996), Chauvet and his colleagues described their feelings in this way:

“During those moments there were only shouts and exclamations; the emotions that gripped us made us incapable of uttering a single word…. Everything was so beautiful, so fresh, almost too much so. Time was abolished, as if the tens of thousands of years that separated us from the producers of these paintings no longer existed. It seemed as if they had just created these masterpieces. Suddenly we felt like intruders. Deeply impressed, we were weighed down by the feeling that we were not alone; the artists’ souls and spirits surrounded us. We thought we could feel their presence; we were disturbing them.”

These modern explorers felt strongly connected across an almost unimaginable chasm of time to the people who had once frequented the cave, and at the heart of this vivid sensation was the images they had created. This is a remarkable thing to consider. ‘Presence’ is certainly a quality that contemporary lovers of art look for and admire in paintings. When viewers stand in front of an original work by the likes of Caravaggio or Van Gogh or Chagall, they often experience a very powerful connection with them. They see their brushstrokes, marvel at their distinctive technique, and get a strong sense of their personal investment in the work, their individual genius and vision. It’s as if the artists are very much alive and kicking and still making their presence felt. Jean-Marie Chauvet and his colleagues had an electrifying sense of that on their first encounters with the cave paintings.

Many of the painted caves discovered across France and Spain have a shrine-like quality and contain evidence that rituals of one kind or another were practised in them.

But the notion of ‘presence’ in art goes way beyond the artist’s personal charisma and touches on an even more profound matter - the feeling that one is somehow being confronted by the mystery and reality at the heart of life. It’s an understanding of presence that modern people, in their enthusiasm for the individual brilliance and skill of artistic superstars, can sometimes overlook. But it’s an important dimension of palaeolithic art which cannot be ignored. The painters of Chauvet Cave were clearly captivated by the multitude of creatures who shared the world with them. Their imaginations were stirred by the grace of the ibex, the power of the bison, the dignity of the horse, the inquisitiveness of the bear, the ferocity of the lion, and their close observation of these animals is striking. There can be little doubt that the behaviour and characteristics of these fellow creatures led them to reflect on the meaning and significance of their own lives. And underlying all of this is a quality of wonder in their paintings, a sense of what the Jewish philosopher, Abraham Heschel, called ‘radical amazement’ at the sheer fact of being alive in such an extraordinary and beautiful world.

Of course, we’ll never know exactly what was in the minds of these ancient artists as they were busy creating their masterpieces twenty thousand years before writing was invented. But archaeologists and anthropologists are convinced that the cave paintings are intimately linked with the beliefs and rituals of Stone Age peoples, and that this was their way of connecting with unseen spiritual realities. Many of the painted caves discovered across France and Spain have a shrine-like quality and contain evidence that rituals of one kind or another were practised in them. It seems that when these people went deep underground to create their images, it was in the belief that they were immersed in, and surrounded by, spiritual power and meaning. As scholar David Lewis-Williams puts it, ‘Every image made hidden presences visible’.

Art still has this power. In the modern world it is rarely produced for overtly religious or ritualistic purposes. Nevertheless, art of any era cannot but bear witness to the unseen, sometimes in ways of which the artists themselves are not aware. Whatever their own philosophical and religious convictions may be, artists who labour in the fields of truth and beauty and meaning cannot help but create work that is allusive and open to transcendence. They cannot avoid the untameable and disruptive presence of their Creator. This will come as no surprise to anyone who has read the Psalms:

Where can I go from your Spirit? Where can I flee from your presence? If I go up to the heavens, you are there; if I make my bed in the depths, you are there also…

The understanding of reality found in the Bible leads to a recognition that wherever people may be on the face of the planet and at whatever point they stand in the long, long history of the human race, they are always in the presence of, and confronted by, the Great I Am, who is the Lord of all times and places.

The spelunkers of Chauvet Cave received an extraordinary gift at Christmas 1994, and through their discovery the rest of the world has been its beneficiary too. It’s a truly wonderful thing to have been given this glimpse into the lives of people so long ago, and through their creative endeavours to recognise our common humanity and the abiding power of art and the imagination. And at the heart of this present to us all was a presence that Jean-Marie Chauvet and his friends felt so vividly. But they were only partly right in linking that sense to the creative artists. For beyond those ancient cave painters is the object of their concern, the One who, as the Welsh poet, Waldo Williams put it, stands before us all as ‘Each witness’s witness, each memory’s memory, life of every life’ - the Presence behind all presence.