The seeds of faith were sown in the life of Nic Fiddian Green by his father. As he has explained recently, he “was shown a way and a faith, and an understanding around the faith of Christianity, in the way my father lived”.

Later, his wife-to-be, Henrietta Hutley, asked him to help create Stations of the Cross for the Wintershall Estate in Surrey where, today, The Nativity and the Life of Christ are regularly performed. Henrietta’s father, Peter, wrote and brought The Passion of Jesus to Trafalgar Square, while her mother, Anne, had the vision for the Stations of the Cross project after a life-changing visit to Medjugorje.

Fiddian Green says that “The Face of Christ has been with me for over 40 years” and that he has “searched for His face through my art as part of my spiritual journey, and also in the work of many others – especially Renaissance artists like Giotto, Piero della Francesca and Michelangelo”.

Fiddian Green, who is internationally celebrated for his monumental equine sculptures, has created a deeply personal and spiritually resonant exhibition entitled The Face of Christ. The exhibition features 20 new sculptures including works in bronze, copper, lead, marble, plaster, and silver, together with a series of drawings. The exhibition ranges from the Nativity to the Resurrection but focuses primarily on the crucifixion.

The exhibition is deeply personal for Fiddian Green because it is informed by the harrowing encounters he had with an array of life-threatening illnesses a few years ago. These caused an obvious and honest creative re-assessment and it is from these experiences that a stronger, deeper and more contemplative vision has emerged. One that permeates the new work via modes of stillness and reflection.

The Face of Christ offers a profoundly meditative engagement with the image of Christ, capturing a sense of serenity, resilience, and transcendence in bronze and stone. In these works, he shows us how his spirit and his faith help him triumph over the physical as he explores the enduring power of faith, suffering and redemption. In the eyes of his work, we feel pain, strength, fear, wisdom and more as he asks questions of the viewer that leave a powerful and spiritual resonance.

Fiddian Green says: “These works are a reflection of my journey of faith. I have come to find that His power to elevate us underpins everything I strive to do and The Face of Christ is an attempt for me to convey in my work all that He conveys in my heart. Christ gives me the key, but will I open the door…?”

While the exhibition focuses on the crucifixion and the face of the crucified Christ, the expression on Christ’s face is generally one of peace, rather than pain. In part, this is because many of the heads of Christ included are images of Christ resting in death prior to the resurrection. The brokenness that the crucifixion brought is shown in these images through damage to the body of Christ, as opposed to the expressions on his face. This is most powerfully the case with ‘Broken for You’, a bronze crucifixion sculpture where Christ’s torso, as well as being scarred by a long spear-like fissure, has also been fractured with the two parts fused together using brace brackets. Similar fissures appear on other of the crucifixion sculptures but ‘Broken for You’ goes furthest in graphically showing the pain Christ endured on our behalf.

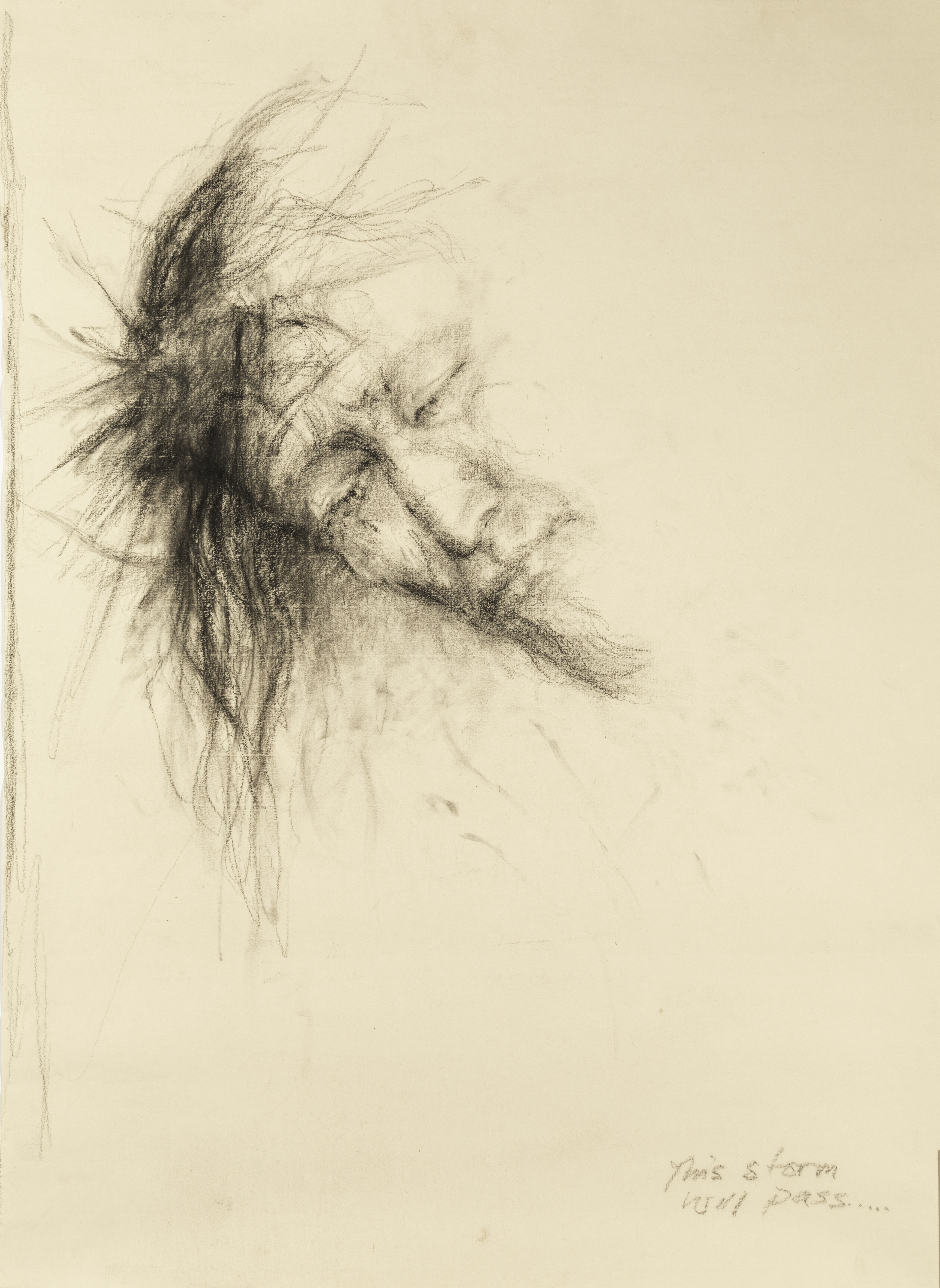

It seems to me that Fiddian Green could go further in revealing the horrors that Christ endured and that his love of Renaissance art with its focus on beauty and balance might hold him back in this regard. Another artist to have regularly depicted the Crucifixion in images shown in mainstream galleries in recent years is Peter Howson, whose images of the crucifixion are much more expressionist graphically capturing the depth of pain that Christ endured. Fiddian Green’s drawings, more than his sculptures, tap into the sense of pain endured, particularly ‘This Storm will Pass’, a partial image of the face of the crucified Christ which in its frenetic pencil-marks and incomplete state speaks particularly powerfully.

Fiddian Green, by contrast, primarily gives us a sense of the peace that he receives from Christ on the face of Christ. ‘I Forgive’, a bronze head of the crucified Christ depicts the love with which Christ looks on us as he endures the cross. ‘Christ is Laid to Rest’ is a huge head encircled by a crown of massive spikey thorns with green verdigris overtones suggesting the sweat and blood of anguish which has led to the completion of purpose that Christ finds in death. ‘Peace’, a plaster sculpture of Christ’s head, is also redolent of the supreme achievement of the cross; ‘It is finished’, meaning that all his work is complete and done, enabling him to rest and enabling us to enter rest.

In these images, Fiddian Green is reading back into the events of the crucifixion the outcomes that it gains for us and showing, in his Christ figures, the peace that he personally finds in the love and forgiveness which overflows from the crucified Christ to each and every human being throughout time and history.

Fiddian Green writes of having “been given materials to use by the God of heaven and earth” – those materials of the earth that he uses in his sculptures – and says that “it is my hope that some of these pieces may rest and resonate with those who see it; that they may find a deep connection by gazing on the works which takes the eye, the heart and the soul to the One who helped me create them”.

While Lent, Holy Week and Easter are often times when art is offered to enable us to walk in the footsteps of Christ it is not common for commercial galleries to specifically invite meditation on these events, so don’t miss the opportunity for contemplation that the Sladmore Gallery is providing through this exhibition.

The Face of Christ, 10th April – 2nd May 2025, Sladmore Gallery, London.