I’ve been teaching college students for almost 30 years now. As much as I grumble during grading season, it is a pretty incredible way to make a living. I remain grateful.

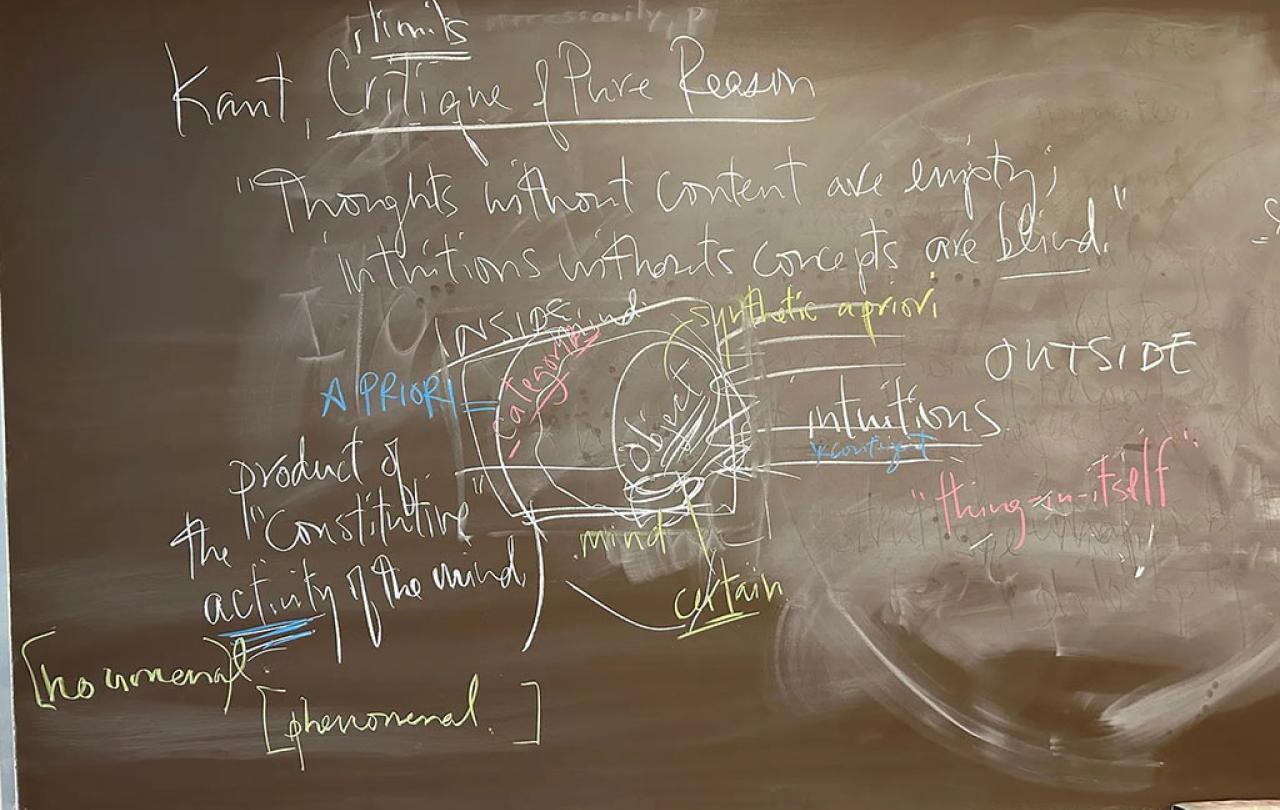

I am not the most creative pedagogue. My preference is still chalk, but I can live with a whiteboard (multiple colors of chalk or markers are a must). Over the course of 100 minutes, various worlds emerge that I couldn’t have anticipated before I walked into class that morning. (I take photos of what emerges so I can remember how to examine the students later.) I think there is something important about students seeing ideas—and their connections—unfold in “real time,” so to speak.

I’ve never created a PowerPoint slide for a class. I put few things on Moodle, and only because my university requires it. I’ve heard people who use “clickers” in class and I have no idea what they mean. I find myself skeptical whenever administrators talk about “high impact” teaching practices (listening to lectures produced the likes of Hegel and Hannah Arendt; what have our bright shiny pedagogical tricks produced?). I am old and curmudgeonly about such “progress.”

But I care deeply about teaching and learning. I still get butterflies before every single class. I think (hope!) that’s because I have a sense of what’s at stake in this vocation.

I am probably most myself in a classroom. As much as I love research, and imagine myself a writer, the exploratory work of teaching is a crucial laboratory for both. I love making ideas come alive for students—especially when students are awakened by such reflection and grappling with challenging texts. You see the gears grinding. You see the brow furrowing. Every once in a while, you sense the reticence and resistance to an insight that unsettles prior biases or assumptions; but the resistance is a sign of getting it. And then you see the light dawn. I’m a sucker for that spectacle.

This is how the hunger sets in. If you can invite a student to care about the questions, to grasp their import, and experience the unique joy of joining the conversation that is philosophy.

Successful teaching is, fundamentally, a work of empathy. As a teacher, you have to try to remember your way back into not knowing what you now take for granted. You have to re-enter a student’s puzzlement, or even apathy, to try to catalyze questions and curiosity. Because I teach philosophy, my aim is nothing less than existential engagement. I’m not trying to teach them how to write code or design a bridge; I’m trying to get them to envision a different way to live. But, for me, it’s impossible to separate the philosophical project from the history of philosophy: to do philosophy is to join the long conversation that is the history of philosophy. So we are always wresting with challenging, unfamiliar texts that arrive from other times that might as well be other planets for students in the twenty-first century.

So successful teaching requires a beginner’s mindset on the part of the teacher, a charitable capacity to remember what ignorance (in the technical sense) feels like. To do so without condescension is absolutely crucial if teaching is going to be an art of invitation rather than an act of alienation. (The latter, I fear, is more common than we might guess.)

Such empathy means meeting students where they are. But successful teaching is also about stretching students’ minds and imaginations into new territory and unfamiliar habits of mind. This is where I find myself especially skeptical of pedagogical developments that, to my eyes, run the risk of infantilizing college students. (I remember a workshop in which a “pedagogical expert” explained that the short attention span of students required changing the PowerPoint slide every 8 seconds. This does not sound like a recipe for making students more human, I confess.)

That’s why I am unapologetic about trying to teach over my students’ heads. I don’t mean, of course, that I’m satisfied with spouting lectures that elude their comprehension. That would violate the fundamental rule of empathy. But such empathy—meeting students where they are—is not mutually exclusive with also inviting them into intellectual worlds and conversations where they won’t comprehend everything.

This is how the hunger sets in. If you can invite a student to care about the questions, to grasp their import, and experience the unique joy of joining the conversation that is philosophy, then part of the thrill, I think, is being admitted into a world where you don’t “get” everything.

This gambit—every once in a while, talking about ideas and thinkers as if students should know them—is, I maintain, still an act of empathy.

When I’m teaching, I think of this in a couple of ways. At the same time that I am trying to make core ideas and concepts accessible and understandable, I don’t regret talking about attendant ideas and concepts that will, to this point, still elude students. For the sharpest students, this registers as something to learn, something to be curious about. Or sometimes when we’re focused on, say, Pascal or Hegel, I’ll plant little verbal footnotes—tiny digressions about how Hannah Arendt engaged their work in the 20th century, or how O.K. Bouwsma’s reading of Anselm is akin to something we’re talking about. The vast majority of students won’t be familiar with either, but it’s another indicator of how big and rich and complicated the intellectual cosmos of philosophy is. For some of these students (not all, certainly), this becomes tantalizing: they want to become the kind of people for whom a vast constellation of ideas and thinkers are as familiar and present as their friends and cousins. This becomes a hunger to belong to such a world, to join such a conversation.

This gambit—every once in a while, talking about ideas and thinkers as if students should know them—is, I maintain, still an act of empathy. To both meet students where they are and, at the same time, teach “over their heads,” is an invitation to stretch into new terrain and thereby swell the soul into the fullness for which it was made. The things that skitter just over their heads won’t be on the exam, of course; but I’m hoping they’ll chase some of them for a lifetime to come.

This article was originally published on James K A Smith’s Substack Quid Amo.