As we seek to understand and grapple with the nature of Muslim-Christian relations in today’s world, we should not imagine that we have to reinvent the wheel. Throughout their shared history, many millions of Christians have lived within Muslim societies and alongside Muslim neighbours, and their experiences, absent from the history of western Europe, offer valuable perspectives for understanding and navigating our current global landscape.

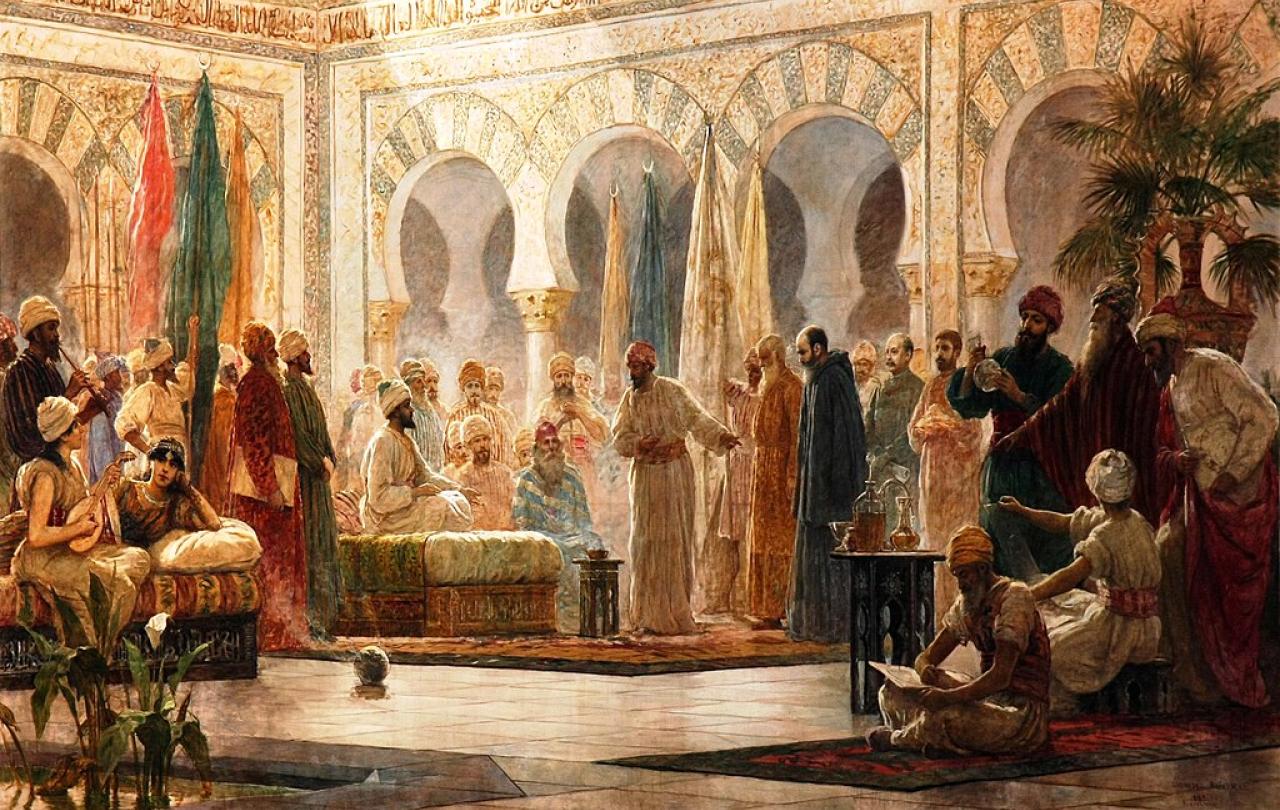

In 782 Patriarch Timothy was summoned for an audience with the Muslim Caliph al-Mahdī at his court in Baghdad. Timothy, just two years into his tenure as Patriarch, was one of the youngest to so far hold the title. As the head of the Church of the East, he oversaw communities scattered across an immense distance, from Syria to China, Sri Lanka to the Kazakh steppe; more believers, indeed, than the Pope in Rome. He himself came from a village near Erbil in northern Iraq, a region that was then, and for a long time after, majority Christian but which also lay near the heart of the Islamic Caliphate. Only twenty years before, the previous Caliph, al-Mahdī’s father, had founded Baghdad, intending it to be the great capital at the centre of the Islamic empire. It had since grown to an enormous size, soon eclipsing any city in Europe, its population over three times that of Constantinople or Rome. Among those who had newly settled in Baghdad was Timothy, who decided to similarly recentre the Patriarchate in the Caliphate’s capital. As such, Timothy was not an unusual sight at court. However, this day’s audience was something out of the usual.

Baghdad was home to more than five monasteries at this time. They served both Christians and Muslims as cool retreats and beauty spots within the bustling city.

Timothy entered the Caliph’s presence and made his courtesies and blessed him.

“Since you are wise,” the Caliph asked, “why do you say that God ‘begat’ a son?”

Over the next two days, al-Mahdī proceeded to ask him questions on the differences between Christianity and Islam: Do you believe in three Gods? Do you not believe that the Qur’an was given by God? Why do you not accept Muḥammad?

Yet, for a Christian in the early Islamic world, to respond to such questions was not without trepidation.

Generally, the Muslim state was not an active persecutor of Christians. Instead, Christians were expected to abide by certain social restrictions. These followed the precedent of a supposed agreement drawn up in the early seventh century between the second Caliph ‘Umar) and the majority Christian populations of the near east during the conquests of the region. Its historicity is doubted, but it came to have a great impact on the rights and responsibilities that Muslim authorities held to exist between themselves and their Christian subjects.

Accordingly, Christians were restricted in their behaviour and dress. They had to distinguish themselves by their clothing, such as wearing a distinctive belt called a zunnār, and they were forbidden from taking Muslim names. They were not allowed to build or restore churches, nor to encourage Muslims to convert, let them in their churches, carry out services in their hearing, or serve them wine. In this way Muslims and Christians would be kept visibly distinct, Christians would be socially subordinated, and Muslims prevented from being led astray, with conversion kept strictly one-way. In return, Muslim authorities would guarantee freedom of belief and extend the protection of the state to Christians. Such was the law in theory.

In the shade of the garden

On Easter day the Christians of Baghdad would come from throughout the city to the monastery of Samālū to take communion. With them too came many of Baghdad’s Muslims to join in the festivities that followed. In the cool shade of the monastery’s beautiful gardens and palm groves they drank wine, danced with young Christians and listened to the sounds of the services, the chanting of monks and priests. This was not an unusual occurrence. Baghdad was home to more than seven monasteries at this time. They served both Christians and Muslims as cool retreats and beauty spots within the bustling city, while their frequent feasts and festivals always attracted many Muslims.

A level of life otherwise invisible in the historical records, such revelries were a source of inspiration for many Muslim poets. Many of their longing verses on the joys of monastery gardens, the sound of Christian services, and the smells and tastes of wine, made their way into poetry collections, such as the tenth-century collection of monastery-themed poems and anecdotes compiled by the Iraqi Muslim al-Shābushtī. For these poets and the leisure class they represented, the transgressiveness of these themes was clearly part of the appeal, but in the background many ordinary Muslims too were freely attending Christian festivities and frequenting monasteries where they were overhearing services and rubbing shoulders with Christians.

While rules existed to stop this mixing they were evidently not enforced. Indeed, the Muslim polymath al-Jāḥiẓ, in his Reply to the Christians written in the mid-ninth century, decried this regular flouting of the rules. The Christians rode highly bred horses and played polo, he complained. They gave themselves Muslim names, failed to wear their zunnārs or hid them beneath their clothes, and draped themselves in fashionable silks. Throughout most of the Muslim ruled near east and Mediterranean, Christians daily rubbed shoulders with their Muslim neighbours, generally without mishap. Christians worked with Muslims and many had Muslim relatives, as individuals and family branches slowly converted. Still these mixed environments could be hazardous for Christians to navigate.

A party in Damascus

At a party in Damascus, a few years prior to Timothy’s audience with the Caliph, a young Christian named Elias mixed alongside Muslim and Christian guests. He had been hired to wait at the party by the Muslim host, the owner of the saddle shop at which Elias worked, and found himself subjected to the taunts and mockery of some of the Muslim guests because of his distinctive dress. As the night wore on they warmed to him and he was invited to join the dancing, for which he laid aside his zunnār. Come morning, however, he was informed by some of the Muslim partygoers that they took this as a sign of his conversion. Terrified of being accused of apostacy from Islam if he was seen continuing to practice Christianity in public, he approached the manager of his workshop, a recent Muslim convert, who assured him that none of this would be reported. Sometime after this, Elias’ family confronted the manager over unpaid wages, and he threatened to report Elias for apostacy. Elias fled back to his home village. However, a few years later he returned, again requesting his unpaid wages. Enraged, the manager reported him to the authorities. He was charged with apostasy and executed.

So relates the account of his martyrdom, written not long after his execution, when he was already being commemorated as a martyr. We can’t be sure on the details. It is possible for instance that the narrative of being tricked at a party covers a more consensual conversion. Yet, parties could be hazardous as well as fun settings. Muslims and Christians freely mixed but there was still an underlying imbalance in social status. We see this in the poetic verses on monastery parties where young Christians often seem to have had little recourse in fending off the advances of older guests. Christians also had to be cautious in how they responded to possible mockery and questioning. Still, many of those executed for apostasy in this period had converted perfectly willingly before later recanting. Conversion to Islam was, in theory, very easy, requiring only the declaration of the shahāda, the Islamic expression of faith, acknowledging that there was no God but God and that Muḥammad was the messenger of God. Once witnessed, leaving Islam was legally impossible. However, again, this was not something that the state was active in searching out. Elias’ story rings true. Had he stayed in the village, he would probably have been fine, but it was a personal workplace conflict that provided the catalyst for his denouncement, at which point the state was compelled to act.

The streets of Córdoba

One of the other great cities of the early Islamic world was Córdoba, which lay at the heart of the Islamic emirate at the other end of the Mediterranean. Like Baghdad it dwarfed all the other cities of Europe and was home to many Christians and Muslims. Here, in 850, a country priest, while on an errand in the city, was approached by Muslims who asked him what Christians believed about Jesus and Muḥammad. The priest, named Perfectus, freely confessed Christ to be God but he was reluctant to offer an opinion on Muḥammad. However, further assured that there would be no repercussions, he did not hold back. He declared Muḥammad to be a false prophet, an adulterer deceived by demons. Enraged, his questioners nevertheless kept their promise and let him go. When, however, he was next in the city, word of his statements seemed to have spread. A crowd seized him, and he was taken before the city’s judge and imprisoned. Several months later he was beheaded.

Perfectus’ death sparked a wave of deliberate blasphemy in the city. Over the next nine years, 33 Christians confronted the judge, stood in the city’s market forum, and even entered the grand mosque, denouncing Muḥammad and provoking the state to execute them. Their actions were immensely controversial among the local Christians. Actions of deliberate provocation intended to lead to martyrdom had been condemned by the early church, and many also saw them as imperilling the freedom they enjoyed from social restrictions. However, like al-Jāḥiẓ, it was a frustration with precisely this lack of distinction between Christians and Muslims that had at least partly inspired the martyrs, concerned that the distinction between Christianity and Islam would be lost too. Yet, there were also 11 individuals executed in these years who had not sought martyrdom. Executed for apostacy, some had converted to Islam and then changed their minds, or been supposedly tricked like Elias, others were the children of Muslim parents who had converted through the influence of a Christian relative. All came from mixed families, many the children of mixed marriages, and, unlike the blasphemers, all had been hunted down by the state after being denounced by relatives or neighbours.

In the early Islamic world, blasphemy and apostacy were the main reasons Christians found themselves facing execution. However, in this too the state was not proactive but acted mainly in response to denouncers, who were often motivated by personal grievances.

Back in Baghdad

Standing before the Caliph, Timothy was fully aware of the perils. In answering al-Mahdī’s questions he was walking a tightrope between blasphemy and conversion. If he responded too stridently in his answers he could find himself, like Perfectus, charged with blasphemy. At the same time though, the Caliph’s questions on the oneness of God and the status of Muḥammad drove at the key elements of the Islamic confession of faith. Al-Mahdī had apparently tried to persuade Timothy’s predecessor to convert during a similar audience, while Timothy’s opponent in the election for patriarch supposedly later converted to Islam under the Caliph’s influence. If Timothy answered too deferentially, he perhaps risked claims of inadvertent conversion, like Elias.

Asked why he believed God had begotten a son, he responded:

“O God-loving King, who has uttered such a blasphemy?”

"Do you not say that Christ is the Son of God?"

"O King, Christ is the Son of God, but not a son in the flesh, he is the word of God.”

He continued to answer the Caliph’s questions with much care and respect.

Did the Qur’an come from God?

“It is not my business to decide whether it is from God or not.”

“What do you say about Muḥammad?” This was the area of greatest sensitivity.

“Muḥammad is worthy of all praise by all reasonable people, O my Sovereign. He walked in the path of the prophets and trod in the track of the lovers of God. All the prophets taught the doctrine of one God, and since Muhammad taught the doctrine of the unity of God, he walked therefore in the path of the prophets. Because of this God honoured him and brought low before his feet two powerful kingdoms. Who will not praise, O our victorious King, the one whom God has praised? These and similar things I and all God-lovers utter about Muhammad, O my Sovereign.”

“You should, therefore accept the words of the Prophet.”

“Which words?”

“That God is one and that there is no other one besides Him.”

“I believe in one God, O my Sovereign, I have learned from the Torah, from the prophets and from the Gospel. I stand by it and shall die in it.”

“We children of men are in this perishable world as in darkness,” declared Timothy. “The pearl of the true faith fell in the midst of all of us, and it is in the hand of one of us, while we all believe we possess it. The signs wrought in the name of Jesus Christ are the bright rays and shining lustre of the precious pearl of faith.”

“We have hope in God that we are the possessors of this pearl,” declared the Caliph.

“Amen, O King,” Timothy replied, “but may God grant us that we may share it with you, and rejoice in the shining lustre of the pearl!”

“We pray,” he concluded, “that the King of Kings would preserve the throne of the Commander of the Faithful.”

Whether this interaction happened, or happened the way Timothy reported it in his letter cannot be known. Certainly he had regular audiences with al-Mahdī and his successors. Earlier in the year he had appeared several times before the Caliph on the matter of restoring various churches along the western border. In Baghdad he was also known as a willing opponent for debate and a well-regarded expert on Aristotle, at a court in which people still regularly engaged in such interreligious debates. But either way, his reason for circulating this letter was clearly instructional, showing others how to avoid the hazards implicit in everyday encounters and conversations. It offered a vision of how to navigate safely between the twin dangers of apostacy and blasphemy, neither compromising Christian beliefs nor recklessly offending Muslim beliefs. While circulated primarily among the leading bishops and schools of the region, these were the individuals and institutions tasked with training priests, monks and teachers, who, like Perfectus, might find themselves the most frequently on the end of similar questions, while they further offered instruction to laity. Originally written in Syriac, the dialect of Aramaic primarily used by Christians, it was soon translated into Arabic and in this form remained popular in the region into the modern-era.

Yet, still, Timothy felt keenly his own weakness and the imperfection of his answers, his inability to explain or persuade.

“I feel repugnance,” wrote Timothy in his introduction to the letter, “on account of the futility of the outcome of the work. But love covers and hides all these weaknesses as the water covers and hides the rocks that are under it.”

Further reading

Full translation of Timothy’s Dialogue with the Caliph al-Mahdī, translated by Alphonse Mingana (1928): Link.

Sahner, Christian C., Christian Martyrs under Islam: Religious Violence and the Making of the Muslim World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University press, 2018).