We live in anxious times, apparently – it’s hard to go a day without hearing someone use the word anxiety. But even as the BBC reports a surge in internet searches for anxiety-related topics, The Times is running editorials which ask whether too many people are being signed off work with ‘anxiety’ because it is now presumed to be pathology rather than a normal part of life.

But what is this thing we call ‘anxiety’ – is it pathological, unavoidable, both, or neither? And are the broad, somewhat existential kinds of anxiety, such as “climate-anxiety”, really the same kind of phenomenon as the “clinical anxiety” that causes some individuals such acute suffering.

One way to explain anxiety is through a biological model of what it means to be human. As human beings we are always driven towards staying alive and maintaining homeostasis. For that we need food, shelter, and social bonds (including procreative bonds) with other human beings. So, our nervous systems and hormones work together, using low levels of anxiety on and off throughout the day to steer us towards behaviours that will satisfy those needs. For example, we might feel agitated and restless when we are hungry – this is a mild sense of anxiety that succeeds in prompting us to seek out food.

Then there is a slightly higher level of anxiety that occurs when something is perceived as threatening our ability to stay alive. For most of us, the first thing we know about that kind of anxiety is a sense of dread, followed by discomfort in the nervous system – jelly legs, a pounding heart. The body is getting ready, priming us for a fight, flight, freeze or fawn response. Again, this kind of anxiety is functional – it keeps us alive and steers us away from dangerous and vulnerable situations.

Because humans are social animals, anxiety works within the social world too, either gently steering us in and out of relationships, or prompting us to moderate our behaviours in a social setting so as to avoid exclusion, or to initiate group responses to danger. Anxiety also plays a role in maintaining the structures and hierarchies of the communities that we form – children behave in class because when they slightly fear the teacher or are anxious to please.

Of course, all of these positive and functional roles for anxiety have their negative flipsides, and excessive anxiety, left untreated, can make us very ill. The many treatments for anxiety as an illness are ancient in origin, stemming from the days long before there were biological models to explain what was going on with our bodies, or drugs and therapies to keep the worst at bay.

Somehow in Aristophanes’ wine-induced monologue, Plato succeeds in naming something deep and intrinsic to the human condition – a certain anxious feeling that pervades life.

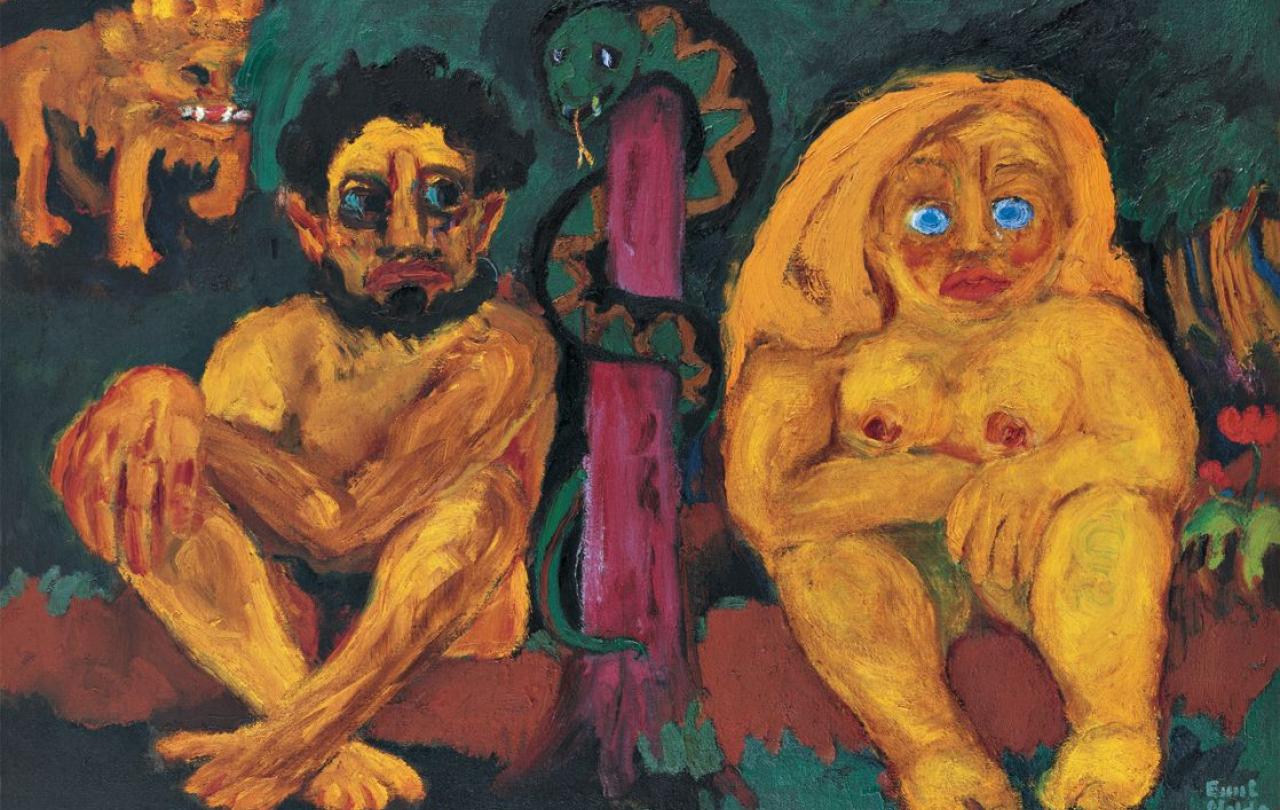

It was the philosophers who first tried to explain this strange discomfort that seemed to pervade the experience of being alive and being human. In around 360 BCE Plato penned his Symposium, in which the character of Aristophanes espouses a theory that humans were once ‘androgyn’ – that is, man and woman connected in embrace. When the gods were angered, they split humans into two, henceforth destined to roam the earth as separate parts, man and woman, each in a perpetual state of agitation to find ‘the other half’ of themselves. This agitation was named as eros – the desiring aspect of love, a restless search for completeness and fulfilment.

It should never be forgotten that Symposium is a bunch of drunk men trying to out-perform each other at oratory. Even so, sometimes drunk men can speak uncanny truths. Somehow in Aristophanes’ wine-induced monologue, Plato succeeds in naming something deep and intrinsic to the human condition – a certain anxious feeling that pervades life. Eros is only one aspect of this; more broadly as humans we feel ourselves as separate to other things and people, as if we are the subject and they are the objects, and everyone and everything is in some sense distant and disconnected from us. Plato placed this feeling all in the body – turning physical longings for connection and satiation into proof that we are, in fact, alive.

However, skip forward a few centuries to Descartes, and his famous dictum: I think therefore I am. Descartes was dubious that the sensations of the body could tell us anything truthful about being alive. After all, the senses can deceive – we can experience eros in dreams just as well as in reality. Therefore, Descartes concluded, the only thing that can assure us of the fact that we are alive and in existence is the fact that we can sit and think to ourselves, “Actually, I might not be alive and in existence right now.” We can’t think that unless we are…um…thinking that – which means that we do in fact exist to think it. In essence, Descartes concluded that anxiety about whether or not we exist is proof of existence itself.

With freedom comes ability to act either for good or for evil, hence the anxiety – it was a certain dread that our works might not serve the God who created us.

It was Immanuel Kant who most famously took issue with this, because for the mind to be able to scrutinize its own existence in this way, it would have to be both subject and object at the same time. Kant proposed that the mind cannot divide and start thinking about itself, and therefore there needed to be a third-party involved, something external to the mind that was essential to knowing about our own existence. This third-party Kant took to be the soul, or something like it, the presence of which could be sensed neither through thoughts nor through bodily sensations but through affects. Affects were pre-conceptual forms of knowledge, feelings of being alive that seemed to emanate from nowhere. And chief among these affects was… anxiety.

The idea that we need a third-party, or a transcendental viewpoint from which to perceive our own existence gained significant traction following Kant, particularly in the work of German Idealists such as Hegel and Schelling. They spoke of the “Absolute” or “Absolute Spirit” – a somewhat pantheistic conception of God, who had created the universe and was continuing to drive the universe’s unfolding. The restless anxiety that humans feel was, Schelling proposed, a consciousness of freedom – humans knowing their own creative power within that unfolding universe. With freedom comes ability to act either for good or for evil, hence the anxiety – it was a certain dread that our works might not serve the God who created us. Although he was no fan of German Idealism, philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard later developed this same idea, characterising anxiety even more strongly as a kind of moral conscience – a realisation of our human freedom in relation to sin. For Kierkegaard, the anxiety of our freedom could be dispelled by making the “leap” into sin, or (better) into godly and upright choices.

Schopenhauer was a contemporary of all these thinkers, but interestingly he took Kant’s thinking in a slightly different direction, avoiding the idea of God at the origins of the universe. Like Plato’s Aristophanes, Schopenhauer identifies the struggle, the ubiquitous anxiety of the human condition, as being the result of dividedness, although he grounds it in a metaphysical separation of the individual from a non-conscious, cosmic whole, which he termed ‘Will’. For Schopenhauer the Will was not divine in the sense of a God-figure, but was a ubiquitous kind of energy pervading the universe, driving humans always to seek pleasure and to avoid pain. Thus, Schopenhauer’s anxiety was rather more of the body than the mind, and the remedies he proposed were to subdue the body though ascetic practices and occupy the mind with art.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, this philosophical (and theological) discussion of anxiety began to converge with the more ‘clinical’ approach to anxiety as a disorder causing frequent panic attacks, melancholy, and other stark physical symptoms. This convergence occurred particularly with the birth of modern psychology. Prior to this, anxiety as an illness, along with most mental illnesses, had been largely considered to be a religious problem, often the result of demon possession. Although by the eighteenth century most talk of demon possession in the West had been dropped from the narrative, anxiety was still very much considered an illness which occurred in the body and was independent of the mind. Dominant theories at this time included imbalanced humours, blood, and bile or (in women) a wandering uterus, (from which we get the English word hysteria, hystéra being the Latin word for uterus.)

One outlier in terms of bodily accounts of anxiety was Thomas Willis, who in the 1600s was the first to propose ‘neurology’ (he coined the term) as a physiological cause of anxiety. Willis made early inroads into studying abnormal function of the brain function and the nervous system as related to anxiety. However, with the rise of the psychoanalytic movement, his early progress in the neurological study of anxiety was largely forgotten until modern times.

When the structures and moral frameworks of a society start to shift and realign, people become more anxious about life, death and everything in between.

In charting their respective philosophical and medical histories of anxiety, both Bettina Bergo and Cheryl Winning Ghinassi identify that the two trajectories, (that of ubiquitous human ‘angst’ discussed by philosophers and that of ‘anxiety’ as a bodily disorder) first become unified in the psychoanalytic movement that was popularised by Sigmund Freud. It should be noted that Freud was a student of philosophy before developing his theories about psychology. His extensive writing on anxiety contains much discussion of energies within the body, life force, eros and divisions within the self – themes which recurred frequently in the works of the philosophers discussed above.

Psychotherapy as a treatment did not develop until the early twentieth century, but there had been a long history of providing retreats or asylums for individuals suffering from anxiety, which by the eighteenth century had developed into an industry based around spas and mineral baths – although only for the fortunate minority who could afford it. By 1900, the “Weir Mitchell’s rest cure” was popular across Europe, combining bed rest, isolation, a milk diet, and massage. However, it was soon noted that rest cure proved most effective when there was a good relationship between therapist and patient, involving significant time spent in conversation – an early form of talking therapy.

Concurrently, some practitioners had also begun experimenting with hypnotism as a way to relieve symptoms of anxiety. (These practitioners included Franz Anton Mesmer, to whom the word ‘mesmerising’ owes its origin.) A young Sigmund Freud witnessed his more senior colleague, Josef Breuer, treating a young woman with ‘hysteria’ using hypnosis techniques. During the hypnosis sessions, the young woman revealed repressed memories of traumatic events from her earlier life.

Freud brought together these observations about talking therapy and hypnotherapy in this early psychoanalytic theory. He posited that the personality was comprised of three parts, id, ego and super-ego, which were in a state of constant conflict. The id represented biological impulses, whilst the super-ego represented one’s inner moral compass. The job of the ego was to mediate the conflict between the two. Focusing mainly on eros (as sexual desires), Freud theorised that where ego could not successfully mediate, for example for example if one was repressing one’s true sexual wishes and allowing the super-ego to dominate, this could cause a build-up of energy in the body, i.e., anxiety. Thus, he promoted sessions between therapists and patients that focused on uncovering repressed fantasies, memories, and dreams. As the twentieth century progressed, Freud’s psychoanalytic theory became increasingly popular, eventually eclipsing the treatment of anxiety as anything other than a purely psychological condition.

These days, Freud’s theories are often maligned as being rather too focussed on sex and sexuality. But, around the same time that Freud was developing his psychoanalytic theories, behaviourist Edward Tolman was discovering that cognition and rationality could affect stimulus response. Logically, therefore, he concluded that cognition could be trained to re-appraise threatening stimuli and react differently. This was developed into what is now known as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which is now the consensus approach to treating anxiety as a clinical disorder.

However, there are also chemical treatments for anxiety; they too have a long history. There is evidence of opium being in use by humans as early as 4000 BCE, and specifically for the treatment of anxiety since at least the 1500s CE. In the 1950’s it was observed that mephenesin, a drug in use as a muscle relaxant, could also relieve symptoms of anxiety. This led to a resurgence of interest in Thomas Willis’ idea that neurology and neurotransmitters played a role in anxiety disorders. What followed was the development of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI’s), which are the most commonly used anti-anxiety medication today. The disadvantage of SSRI’s and other medicated approaches to anxiety is that symptoms usually return as soon as the medication is stopped, thus the use of drugs is often combined with other types of therapy such as CBT.

A record number of people in the UK are now being treated for anxiety in these ways, probably more than official statistics can count, given that many self-refer to private providers of CBT and other talking therapies. Is this because we live in more anxious times? It actually may be so. As we observed at the start of this discussion, anxiety plays a role in human social ordering, and theologian Paul Tillich was one of several European thinkers who, in the aftermath of the second world war, observed than when the structures and moral frameworks of a society start to shift and realign, people become more anxious about life, death and everything in between. This, he proposed, is because anxiety can put “frightening masks” over people and things, that make them appear more threatening than they really are. If anxiety is telling us to pay attention to the social order and hierarchy around us, but at the same time the structure of that order and hierarchy is unstable and untrustworthy, then anxiety roams untethered to a clear course of action, causing all manner of mischief in both the body and the mind.

Is social order and hierarchy unstable in twenty-first century Britain? Trust in politicians is certainly at an all-time low. We only have to open a newspaper to read that the COP conference was probably blah, blah, blah and yet another high-profile public figure is being investigated for sexual misconduct or fraud. Whether there is a direct link between this, and the rise of people being diagnosed with anxiety disorders is a tricky call to make – we can’t assume that correlation always equals causation. Furthermore, rigidly stable and strongly hierarchical social orders tend to end up as dictatorships, and we surely don’t want to go there. But it may be worth considering what we can do on a micro-level, looking at our own families, friends and immediate social networks. There may be people who are really struggling, their bodies full of uncomfortable sensations, their minds imposing frightening masks onto ordinary people and things. Perhaps Aristophanes was onto something – not that sex is the answer (remember, he was full of wine, and this was ancient Greece) – but that human connection, embrace, be it physical or emotional, may be what that anxiety is ultimately striving towards.