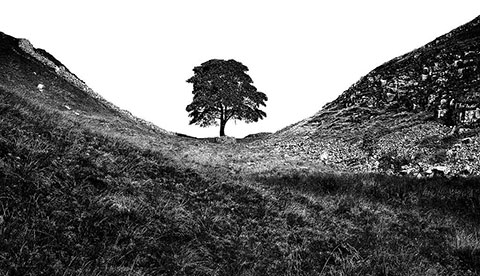

News of the felling of the Sycamore Gap Tree was greeted across the country with shock, sadness and disgust. Shock at the wanton vandalism; sadness at the loss of an iconic feature of our British Isles; disgust at the kind of nihilism it must have taken in the mind of whoever did the deed. Predictably social media blew up. I blew up with it. This was ‘our’ tree - held which such affection by those of us who knew it across the nation as to be almost sacred. The spiteful disregard for that affection felt truly shocking.

The most natural reaction to this is anger. “Throw the book at whoever did it!’ was the general feeling - whether it was the 16-year-old boy first arrested or the 60-year-old man detained later. No motive could justify such a mindless act.

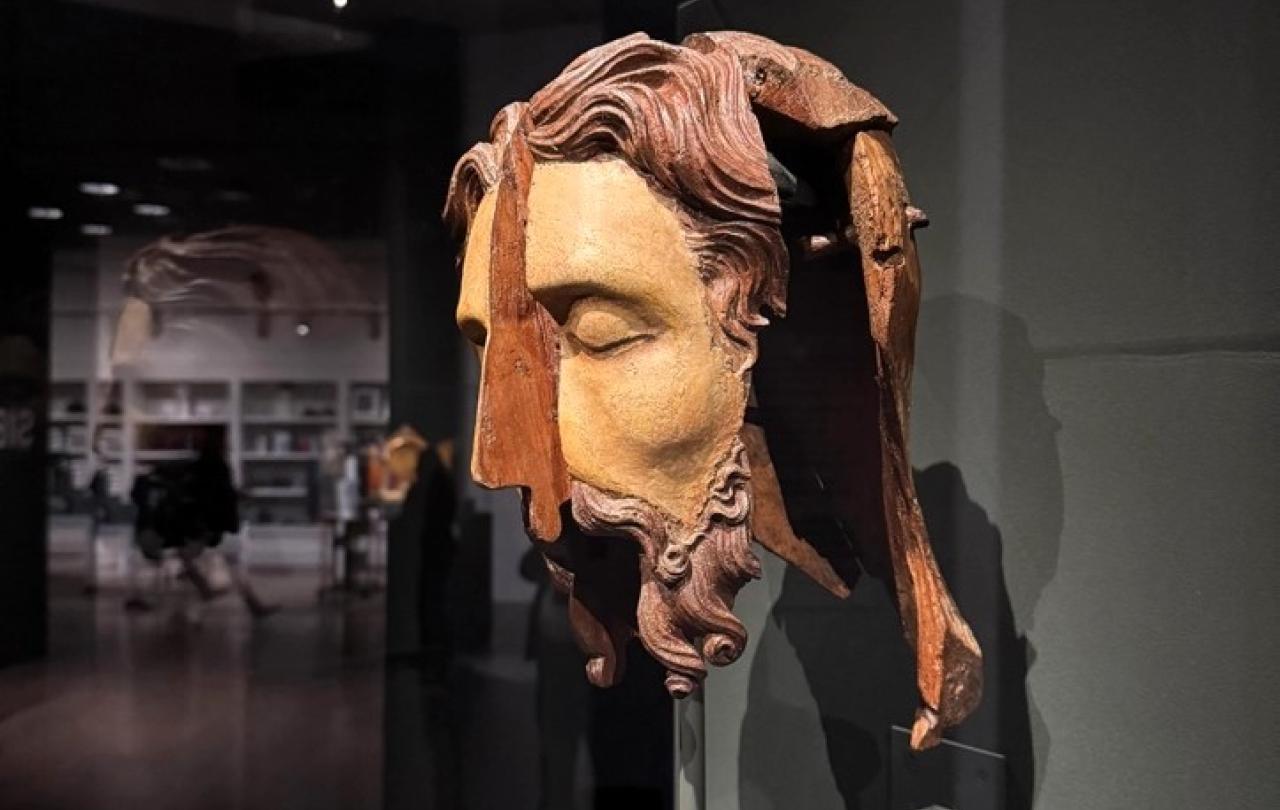

But then came the double shock for me. A jarring recollection that it was the story of the felling of another great tree that had been the seed of inspiration from which grew my entire historical fiction series, The Wanderer Chronicles. And in that story, the man doing the felling seemed to me something of a hero. The tree in question was a mighty oak, dedicated to Donar (better known as Thor) the god of thunder, which once stood in the province of Hesse in central Germany. In the early 8th century, an English missionary, known to history as St Boniface, took an axe to Donar’s Oak, a sacred place of worship to the local pagan inhabitants, even as a large crowd of them stood by raining curses on his head. Boniface would have justified his act of vandalism on religious grounds: the tree was the site of horrific human sacrifice and rituals of witchcraft, and must be destroyed, in part to prove the impotence of this pagan god.

Shocking as his act must have been, Boniface’s aim was not to offend. It was to overthrow. To overthrow a system of religious and spiritual oppression. A system of cruelty, death and bondage. In a sense, it was an act of expulsion of false gods who demanded everything and promised nothing in return. That would have been his justification, at least. And in its place, he intended to plant a new culture of faith, freedom and forgiveness; of truth and love. It’s telling that he used the timber from the fallen oak to build a church.

The event marked the beginning of the widespread destruction of many sacred groves and other places of pagan worship in the decades that followed, symbolic of the supplanting of one pre-existing culture by another, more powerful culture on the rise.

So, can Boniface’s good intentions be distinguished from the apparently nihilistic felling of the Sycamore Gap Tree in our own day? I think they can. But no doubt many would disagree.

After all, these days, we find the idea of one culture asserting itself over another almost as abhorrent as the human sacrifice Boniface was trying to suppress. Certainly, to post-modern sensibilities and values, religious motivations no longer justify any kind of cultural vandalism. Few would have much sympathy for the Taliban’s destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in 2001. Nor for the deliberate arson attacks in the mid-nineties on over fifty churches in Norway by neo-pagan Black Metal bands. Even today, the demolition of a Palestinian mosque by Israeli shells as an act of retaliation attracts media opprobrium, no matter the human death toll that provoked it.

So, is there any good for which vandalism may be justified?

In a world and culture that feel ever more divided, perhaps the Sycamore Gap Tree, even in its destruction, can give us some hope, some fleeting moment of cultural unity.

The protest actions of environmental groups like Just Stop Oil or Extinction Rebellion fall into that vein, and strongly divide opinion. They proclaim a new gospel of environmentalism. Turn around, mend your ways, and be saved. (Although is it really just an old message of paganism: Appease the gods of sun and thunder or else face oblivion?) In any case, it’s a message burning with no less zeal than did old Boniface’s. And while they may not agree with their methods, many would at least agree with their cause and motive. The question is: how far can you stretch a point?

The fact is that there is much that we do not agree on. Borders, taxation, healthcare, education, marriage, sex and gender, even what constitutes a human life. Cultural divisions seem to grow only wider. Increasing mistrust has us standing in opposition to one another - vitriol and disdain filling the space between us. Two tribes in a stand-off. Rather like the two hills that form the gap where that beautiful tree stood until last week. The gap is empty now. The tree is what brought them together. The tree was what completed the whole scene. Without it, we see only the empty air between the two opposing hills.

In a world and culture that feel ever more divided, perhaps the Sycamore Gap Tree, even in its destruction, can give us some hope, some fleeting moment of cultural unity. Trees still represent to us an essential good. Their existence transcends the passage of our short lives. They stand through storm or shine. They sink their roots deep into the good earth. They stretch their limbs up to the skies. They are a metaphor for a life well lived.

The felling of this iconic and beautiful tree is a pang we can all feel, the more so because it seems to have been done as a naked act of vandalism with - so far - no justification offered. Maybe this then is its greatest legacy: that, rather than reaching for the easy emotions of anger and blame, we can transcend our differences for just a moment. And allow ourselves to be reminded that, more than we ever realised, we loved that old tree. And we shall miss it now it’s gone.

If we can all feel that, perhaps there’s hope for us yet.

The Sycamore Gap Tree as was.