The football season has begun. And with it, the usual rigmarole of adverts, fantasy football and over-priced shirts. But this season has a slightly different feel to it. Perhaps it is the obscene - and record - amount of money that was spent in the transfer window (benefitting the biggest clubs), or the sour taste of the Isak saga between Newcastle and Liverpool.

Or maybe there is just a malaise with the game that has been growing for years and is now perceptible just below the surface. Friends and family tell me they have lost interest in football, echoing the words of former Chelsea and England player John Terry who recently made headlines by lambasting the state of the modern game as ‘boring’ . The tendency for one team to defend while a more technically gifted and drilled team tries to break them down means ‘You don't see many shots,’ according to Terry.

His thoughts reminded me of comments made by pundit Gary Neville a couple of months ago after a dull 0-0 draw between Manchester United and Manchester City:

‘This robotic nature of not leaving our positions, being micro-managed within an inch of our lives, not having any freedom to take a risk to go and try and win a football match is becoming an illness in the game'.

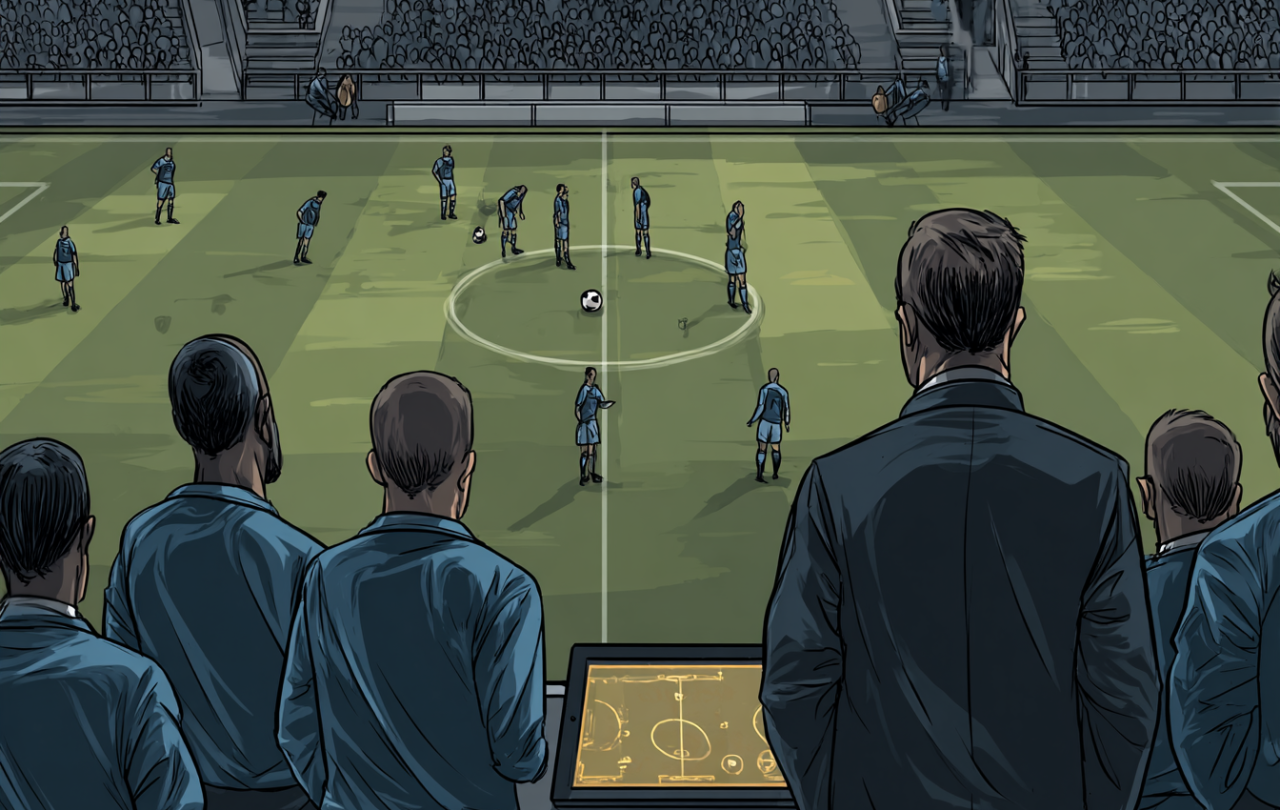

Neville and Terry are referring to the style of play inaugurated by Manchester City manager Pep Guardiola who has undoubtedly revolutionized how football is played in the last decade. The style is geared towards complete control and domination, ironing out any potential errors and minimising risk. It is statistics and data driven, with managers and coaching staff constantly looking at iPads during matches and clubs employing data analysts.

This strategy has of course been wildly successful for Man City in recent years. I don’t think these former players are contesting these remarkable achievements or that this style of football can’t be inspiring and entertaining when executed by players at the top of their game. But because it has become such a dominant way of playing, worse players and teams feel that they have no option but to mimic it. The result is often a boring game with neither team willing to take risks as they are desperate to keep possession. Just look at popular memes comparing wingers from 20 years ago putting crosses in the box compared to simply passing backwards.

Liam Manning, the former manager of my team, Bristol City, very much models himself on this data-driven Guardiola style. Tellingly, one of his catchphrases in interviews refers to ‘taking the passion out of the game’. By this he means ensuring that players keep cool heads and stick to the game plan - but I wonder if he inadvertently betrays the philosophy Neville and Tarry rail against: it is passionless, soulless and mechanical, less open to moments of surprise and unexpected brilliance.

To put my cards on the table, I agree wholeheartedly with Neville. Modern football in my estimation has changed beyond recognition even from the 90s when I grew up. While I cannot deny that some of this has been for the better – stadia safety and decrease in hooliganism for instance – I lament the introduction of VAR and its flawed search for objectivity, the replacement of stadia rooted in the heart of the communities which gave rise to them with soulless bowls located outside of town and the expense that often prices poorer fans out of the game.

Are Neville, Terry and I just hopeless Luddites longing for a past that would inevitably pass away, or is there a deeper philosophical point to all of this? Perhaps. The French Christian thinker Jacques Ellul (1912-1994) critiqued modernity’s propensity to seek ever more efficiency no matter the cost. The French word he gave to this was ‘technique.’ While this is often translated simply as ‘technology,’ it is wider and deeper than this. He describes it as ‘the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of activity.’

In a ‘technological society,’ efficiency rather than creativity, beauty or freedom becomes the norm. It is not hard to see this all around us as we scan our shopping on machines to minimise time-consuming personal interaction, use our pocket computers to organise our lives and dominate our attention all the while we do not know our neighbours’ names. Most Western institutions, the systems of business, politics and morality (and perhaps now football?) have been consumed by this system.

Technique, according to Ellul, is not any one person or group’s fault, but develops its own internal and de-humanising logic which will never reach its goal as it searches forever greater efficiency:

‘proceeding at its own tempo, technique analyses its objects so that it can reconstitute them; in the case of man, it has analyzed him and synthesized a hitherto unknown being.’

But the spiritual consequence of technique is a flattened and banal account of human life, desacralizing the world. ‘Technique denies mystery a priori. The mysterious is merely that which has not yet been technicized… Nothing belongs any longer to the realm of god or the supernatural. The individual who lives in the technical milieu knows very well that there is nothing sacred anywhere… He therefore transfers his sense of the sacred to the very thing which has destroyed its former object: to technique itself.’

There is a clear parallel here with the principalities and powers the Apostle Paul warns against in the Bible: ‘For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.’

What is the antidote to technique in football and elsewhere in life? It is tempting to collapse into a fatalism assuming the march of technical and de-humanising efficiency is unstoppable. Ellul acknowledges the potency of technique but suggests that the greatest weapons against its totalising control are both an awareness and consciousness of its methods and consequently a certain conception of freedom which will willingly not conform to its pattern. ‘Freedom is completely without meaning unless it is related to necessity, unless it represents a victory over necessity… We must not think of the problem in terms of a choice between being determined and being free. We must look at it dialectally, and say that man is indeed determined, but that it is open to him to overcome necessity, and that this act is freedom.’

In footballing terms this might be seen in an enigmatic figure like Khvicha Kvaratskhelia who seems to belong to another era and whose national team Georgia lit up Euro 2024 with their fearless and free flowing play, or by supporters applauding players who take greater risks even if they do not come off. In life in general this might be expressed through consciously avoiding the ‘necessity’ of efficiency: like choosing to do things more slowly like queueing at a supermarket checkout rather than using the automated machine, or walking to rather than driving where possible.

For Ellul and Christians, however, the ultimate liberation from enslaving systems comes in the form of a God revealed in Jesus Christ, who lives a life wholly free from such slavery and takes upon himself the debt and weight enslaved humans hope to escape on their own. As Paul puts in another one of his letters: ‘It is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Stand firm then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by the yoke of slavery.’

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief