It used to be easy to assume that other religions are wrong and ours (or our non-religion) is obviously right, without even giving reasons. Those who belonged to ‘other religions’ were far away from us, foreign in their culture and clearly wrong about so many things. But we no longer live in a society with a common religious framework. Members of different religions rub shoulders with one another and with ‘nones’, those of no religion, every day. When those we respect – believe and live differently to ourselves, we are forced to consider the possibility that their way of life may be reasonable and not absurd. We see how arrogant and immature it is to assume that our culture’s way of doing things is superior. It is like assuming that the nearest house to where we are standing is bigger than houses further away – i.e. it is to forget the perspective on the world which we have simply because of where we are and how we grew up.

We have learnt to celebrate cultural diversity as a good thing, not a threat or a problem. So should we do the same with religious diversity? Is it possible to be ‘religiously neutral’? If one religion is right, does it mean all others are wrong? Or is it better to believe that ‘all religions lead to God’?

Cultural plurality vs. religious plurality

There are many definitions of the word ‘religion’. Some have even claimed that it’s a false category made up by colonial powers who projected Christian categories onto non-Western cultural expressions. However, there is a coherent core to the meaning of religion which connects the word’s historical origins to today’s context.

Long ago there was no word for religion because it was simply an aspect of culture; there was no concept of any divide between ‘natural’ and ‘supernatural’, or ‘physical’ and ‘spiritual’. But at some point, the ancient Romans noticed something about the nations they conquered that could not be explained simply as a cultural practice, which had to do with the ‘worship of the gods’. So they invented the word religio which literally means either ‘reading again’ or (more likely) ‘binding again’. Throughout this article I will take this ancient original meaning as a starting point, using ‘religion’ to mean the ‘bond’ between humans and ultimate reality, the commitment we feel towards what lies beyond the visible world, and our indebtedness to whatever gives us all we have and are. Although in the ancient world it was possible to worship many gods at once, today most religions are exclusive, claiming absolute allegiance and offering an ethical framework along with ritual practices. That is why this definition of religion – of an ultimate bond of allegiance – is the most helpful for engaging with today’s situation.

To believe something does not only mean to think it true in your head. It means to follow the implications of that belief in your behaviour and life decisions, even when it costs and means doing things you’d rather not do.

If we understand religion as our whole-life commitment to what is of ultimate value and importance, it becomes obvious that for those who are deeply religious, their religion is all-encompassing and transforms how they think and act in every part of life. That is why asking about the truth of a religion is not a fun pastime for idle curiosity. It changes your behaviour. To believe something does not only mean to think it true in your head. It means to follow the implications of that belief in your behaviour and life decisions, even when it costs and means doing things you’re rather not do. We all have skin in the game when it comes to religion.

But how can we commit to a single religion when there are so many options that seem equally plausible? In other words, how do I seek the truth, and how do I know it’s the truth when I’ve found it? Let us begin with three common approaches to religious pluralism in contemporary society.

The elephant and the mountain

A popular model imagines each religion as a blind man touching a different part of an elephant. One says the elephant is like a snake, another that it is like a wall, and another that it is like a tail. They disagree over what the elephant is like, because each of them has only part of the truth, and none of them can see the whole truth.

A similar image is that of a mountain, with the truth at the top, and each religion seen as a path up the mountain. Each of us must pursue the truth as it seems to us, and the closer we get to the truth, the closer we will come to each other, until we reach the top together.

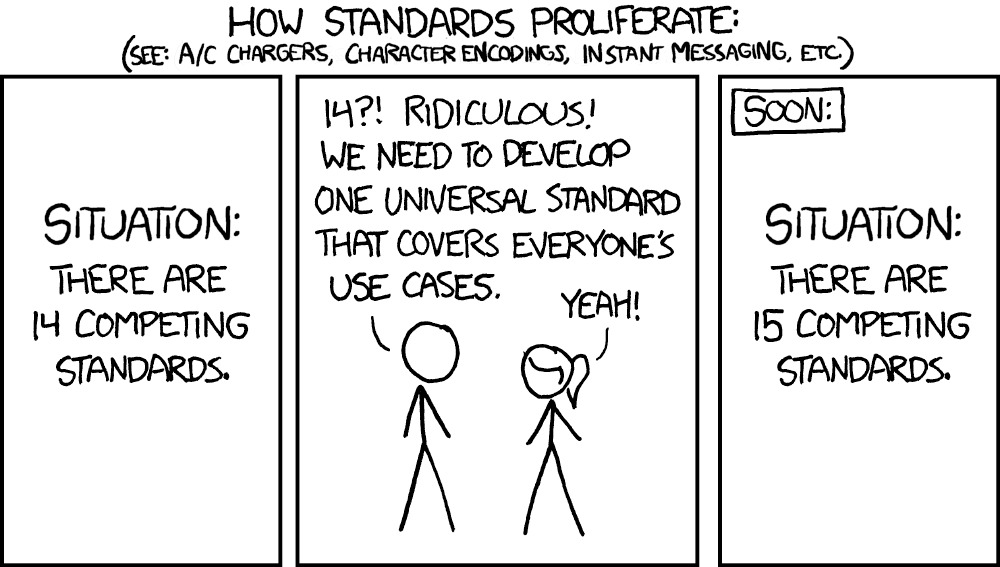

The main problem with this way of thinking about multiple religions is that both analogies – the elephant and the mountain – assume that it’s possible to have a perspective that is superior to any existing religion. If you can see the elephant, then you are not yourself one of the blind men; by implication you have far greater insight than them. If you can see the paths up the mountain, then you can’t be on any of them. The adopter of the analogy sees themselves as more enlightened and closer to the truth than any of the particular religions. This means unconsciously assuming a privileged (and rather patronising) super-religious point of view that surveys all the religions from a non-committed standpoint. But this is simply to create a new religion and to evaluate all the existing religions in light of it. It is the religious equivalent of doing what is done in technology that this XKCD comic makes fun of:

This view also assumes that all the manifold teachings of every religion are compatible and non-contradictory, which seems a stretch. To be sure, many aspects of religious practice are often seen as equivalent cultural expressions – priests, rabbis, imams, and gurus being roughly equivalent, or churches, mosques, temples, and synagogues, or the Bible, the Koran, and the Bhagavad Gita. Even these ‘equivalences’ turn out to be far more complicated than a superficial glance imagines. More obviously, the ethical teachings for life-guidance contain incompatible ideas. You can only really see the incompatibility if you’re trying to live according to these teachings. Then you will find that it's impossible to follow all of them at once. To switch to politics as an example, should Marxism, Nazism, and Capitalism all be seen as paths up the same mountain? Are these political models all like blind men or ways up a mountain? The near-universal repulsion to this idea is the root of Godwin’s Law (i.e. if there’s anything we all agree on, it’s that Nazism is bad). If the elephant/mountain analogy doesn’t work for politics, why would we assume that it works for religions? We can only assume that if we think ourselves in a position to judge all religions by some standard external to any of them. Where did we get that standard from? Each religion claims to be such a standard itself. To make the point really clear: even Nazism is only bad in light of a particular set of religious and ethical commitments, and only those commitments can provide the reasons for why Nazism is bad.

For a religious practitioner – for anyone who has left the comfortable ivory-tower armchair of comparative religion and is seeking serious guidance on how to live and understand the world – this super-religious position is not an option. The only thing we can do is to take a position concerning these questions, which is to be one of the paths, be one of the blind men, and no longer pretend to have any superior viewpoint.

The pick-n-mix buffet

I would summarise this view as saying, in essence, “I don’t think any one religion has the whole truth. They all have some things right and some things wrong. I pick the bits that are good about each religion and kinda go my own way.”

This view has soared to great popularity in recent decades. It seems eminently reasonable and mature, and by contrast, to imagine that one religion happens to have everything right seems naïvely narrow-minded. Isn’t it better to filter each religion for what’s best about it?

But this view also has a problem. A religion claims to be a guide to understanding what is good and bad in the first place. If each of us were able to judge good and bad reliably and consistently for ourselves, there would be no different religions in the first place – they would never have existed. This pick-n-mix approach assumes the opposite: that I already have the truth, and am therefore able to recognise its presence or absence in the world’s religions. This view hasn’t got past the first hurdle of cultural relativity, which is to understand that all knowledge is situated in a particular culture and moment in history. The holder of this view, like the holder of the previous view, has created a new religion for themselves, with a single member who is also its high priest.

Each of the major religious traditions developed over thousands of years, and contains great riches and wisdom from across many ages and cultures. They deserve respect at the very least. What makes any 21st century individual think that they have deeper insight into the truth than any of these great, long traditions of belief and lifestyle? It would be better to belong wholly to any of them, to submit to its teachings even when they are uncomfortable and conflict with contemporary wisdom, than to take this supremely arrogant standpoint of claiming to be the judge of them all.

Can you belong to more than one religion?

This is another common question for those who engage with the question of religious pluralism. It is worth taking seriously because there are people who mean it sincerely and are not just spectators who judge from a distance. I have a friend who tried for a long time to be a faithful Buddhist and Christian at the same time. He emphasised the overlap between the two, especially in the emphasis on compassion, self-denial, and not belonging to the world. He drew on the spiritual resources of both as much as he could, and tried to find ways of reconciling apparent contradictions between them. But one day he realised that this wasn’t working for him, although he couldn’t quite explain why. He was feeling torn between the two, as he tried to go deeper into each. Why is it that I feel compelled to pursue one at the expense of the other, he asked me? This is the answer I gave.

Suppose you went to the Buddha and asked him ‘what do you think of Jesus and of following Jesus?’ And suppose the Buddha said, ‘Jesus is great! What a great idea for you to follow him!’ And suppose you took the Buddha’s advice and chose to follow Jesus. What would be the basis for your trust in Jesus? It would be a consequence of a prior trust in the judgment of the Buddha. Or suppose the opposite: that you went to Jesus and asked him, ‘what do you think of the Buddha?’ and Jesus said, ‘The Buddha is a wonderful example of the values of the Kingdom of Heaven. He is worth listening to.’ You would then learn from the spiritual wisdom of the Buddha, but only because Jesus suggested it. In both cases one is the supreme judge who judges the other, even if that judgment is positive.

There can only ever be one supreme judge in your life, where the buck truly stops. There can only be one final arbitrator, because no matter how similar any two may seem, eventually there will come a place where they tug in different directions. For many people, that supreme judge is really themselves, even if they’re not aware of it. But to belong to a religion means to have submitted to that religion as the supreme judge of reality, which entails subordinating your judgment to the judgment of that religion.

Now, if all the above is correct, then the question of religious pluralism cannot be approached or evaluated from a transcendent non-committed position. Even non-religion turns out to be using a standard of truth and goodness to judge other positions. There is no ‘neutral’ way of evaluating or positioning the diverse religions in relation to each other. The only way to do it is from a particular religion. What, then, is the Christian approach to other religions? How should Christians think about them? That will be the topic of a second article.