When you go abroad, how do you navigate language differences? Do you just stick everything through Google translate? Or put a few weeks into Duolingo before you go? Or maybe you just speak a bit louder in the hope that that will somehow smooth over any misunderstandings?

Recently, my wife and I went to Italy for a week. Neither of can speak a word of Italian and we were taking our toddler Zachary with us (who can speak even less Italian), so we booked into a big resort where we knew staff would be able to speak some English if we needed anything for Zach. Even so, we tried learning a few words and phrases:

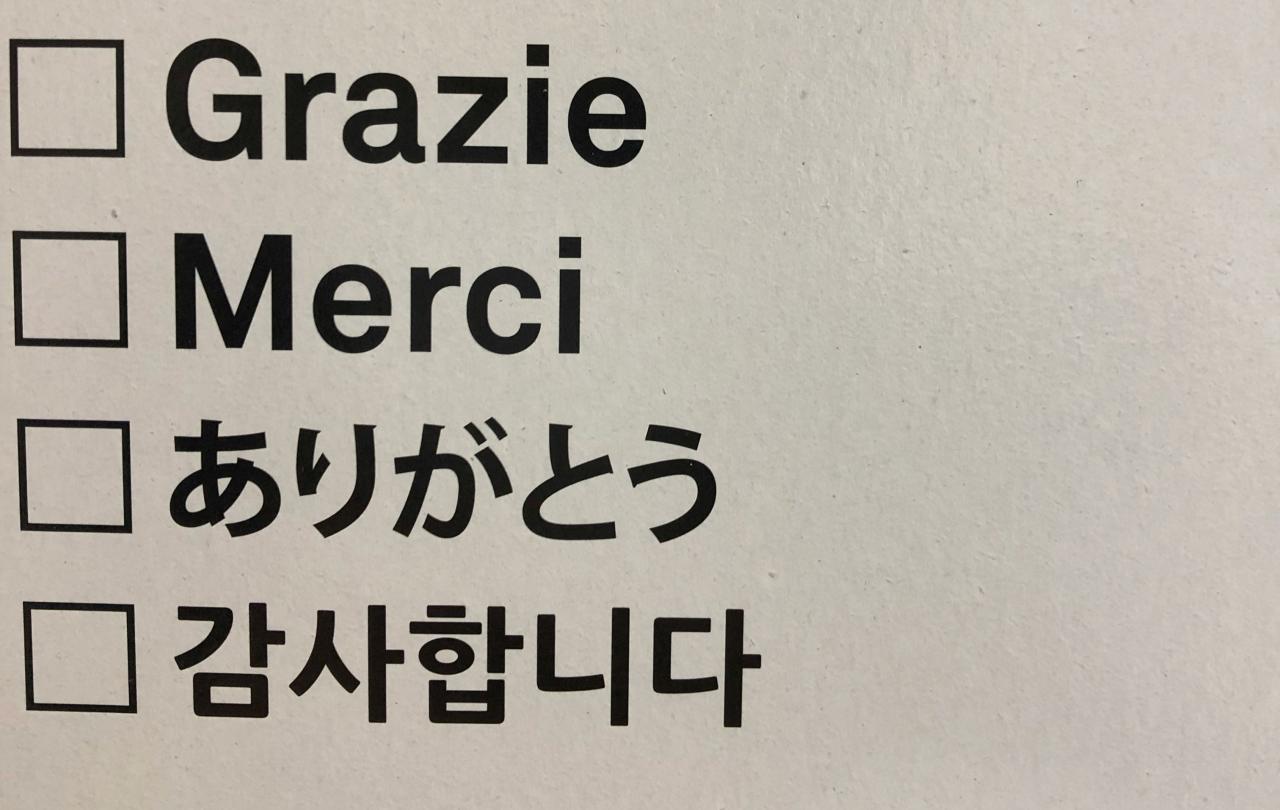

‘please’,

‘thank you’,

‘could I have …?’,

‘where is the …?,

‘please forgive my toddler, he hasn’t learned to regulate his emotions yet’.

That sort of thing. Just some basics to get by.

Of course, what happened was exactly what happens every time I speak another language. I try my best to make an effort, people immediately realise I’m a struggling and they put me out of my misery by replying in English anyway.

All this reinforces the importance of deep and rigorous language learning in society. All this makes the continued diminishment of university modern language programmes rather odd, and more than a little unsettling.

The University of Nottingham has announced it is terminating the employment of casual staff at its Language Centre. This will see the end of numerous classes for students and others in many languages, both ancient and modern, including British Sign Language.

Nottingham is not alone in this. The news comes in the immediate aftermath of a review into the University of Aberdeen’s decision to scrap modern language degrees in 2023, which found the decision “hurried, unstructured, and dominated by immediate financial considerations.” (Not that we needed a review to tell us this). The University of Aberdeen has partially reversed the decision, continuing its provision of joint honour degrees, if not single honour language degrees.

Elsewhere, in January, Cardiff University announced plans to cut 400 academic staff, cutting their entire modern language provision in the process. In May, the University revealed that it would reverse these plans, with modern languages continuing to be offered (for now), albeit it a revised and scaled-down manner.

The situation is bleak. As a theology lecturer who works for a Church of England college, I’m all too aware of the precarity my friends and colleagues in University Arts and Humanities departments face across the sector. But I was also naïve enough to think that languages might be one of the subjects that would be able to survive the worst of education’s deepening malaise given their clear importance. How wrong I was.

There are the obvious causes for despair at the news of language department cuts. One the one hand is the human element of all this. People are losing their jobs. Moreover, as casual workers, the University had no obligation to consult them about the changes or provide any notice period, and so they didn’t, because why would a university demonstrate courtesy towards its staff unless it absolutely had to? As well as losing jobs and whole careers, people will lose sleep, and perhaps even homes and relationships as a direct result of the financial and emotional toll this decision will take on staff. My heart breaks for those effected.

And yet, the move is also evidence – as if more were needed – of the increasing commercialization of Higher Education. A statement from the University said the decision to cut languages in this way was the result of the Language Centre not running at a “financial surplus.” The cuts will instead allow the University to focus on “providing a high-quality experience for our undergraduate and postgraduate students.”

And there we have it. Not even a veneer of pretence that universities operate for the pursuit of truth or knowledge. No, nothing so idealistic. A university is business, thank you very much, here to offer an “experience”. And when parts of businesses become financially unsustainable, they’re tossed aside.

Languages aren’t just ways of describing the world we see, they’re also ways of seeing the world in the first place.

But cutting language offerings isn’t just a personal and a societal loss, it’s also a huge spiritual and moral failure. And that’s because of what language fundamentally is. Let me explain.

It can be tempting to think of words as simply ‘labels’ we assign to objects in the world, with different languages using a different set of ‘labels’ to describe the same objects. As a native English speaker, I might see something with four legs and a flat surface on top and call it a ‘desk’. Someone else with a different native language might call it a Schreibtisch, or a bureau‚ or a scrivania, or a tepu, or a bàn làm việc. You get the point: we might be using different labels, but we’re all ‘seeing’ the same thing when we use those ‘labels’, right?

Well, it’s a bit more complicated than that. Languages aren’t just ways of describing the world we see, they’re also ways of seeing the world in the first place. As such, languages have the capacity to shape how we behave in response to the world, a world itself suggested to us in part by our language(s). As twentieth-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once wrote, “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

Let me give you just one example. English distinguishes tenses: past, present, future. I did, I do, I will do. Chinese does not. It expresses past, present, and future in the same way, meaning past and future feel as immediate and as pressing as the present. The result of ‘seeing’ the world through a ‘futureless’ language like this? According to economist Keith Chen, ‘futureless’ language speakers are 30 per cent more likely to save income compared to ‘futured’ language speakers (like English speakers). They also retire with more wealth, smoke less, practice safer sex, eat better, and exercise more. The future is experienced in a much more immediate and pressing way, leading to people investing more into behaviours that positively impact their future selves, because their view of the world – and their future selves’ place within the world – is radically different because of their language.

Different languages lead to seeing the world differently which leads to differences in behaviour. In other words, there are certain experiences and emotions – even certain types of knowledge and behaviours - that are only encounterable for those fluent in certain languages. And this means that to learn another language is to increase our capacity for empathy. Forget walking a mile in someone’s shoes, if you want truly to know someone, learn their language.

In my day job as a lecturer, when I’m trying to encourage my students – most of whom are vicars-to-be – to learn biblical Greek and/or Hebrew, I tell them it will make them more empathetic people. It may make them better readers of the Bible, it may even make them better writers too but, more than anything else, students who learn languages will be better equipped to love their neighbour for having done so. They will get a better sense of the limits of their world, and a greater appreciation for the ways in which others see it too. Show me a society that is linguistically myopic, and I’ll show you one that’s deeply unempathetic. I can guarantee you of that.

We ought to be deeply, deeply concerned about the diminishing language offerings in the UK’s Higher Education sector. To open oneself to other languages is to open oneself to other ways of seeing the world. It is to be shown the limits of one’s own ways of seeing. Learning a language is a deeply humble and empathetic act. And isn’t humility and empathy in desperately short supply at the moment?

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief