“We may understand the statistics of violence against women, and the catastrophic effects such violence has on the fabric of society, but we don’t comprehend it until it is associated with a face, a voice, a story.”

Christopher Bailey, World Health Organization

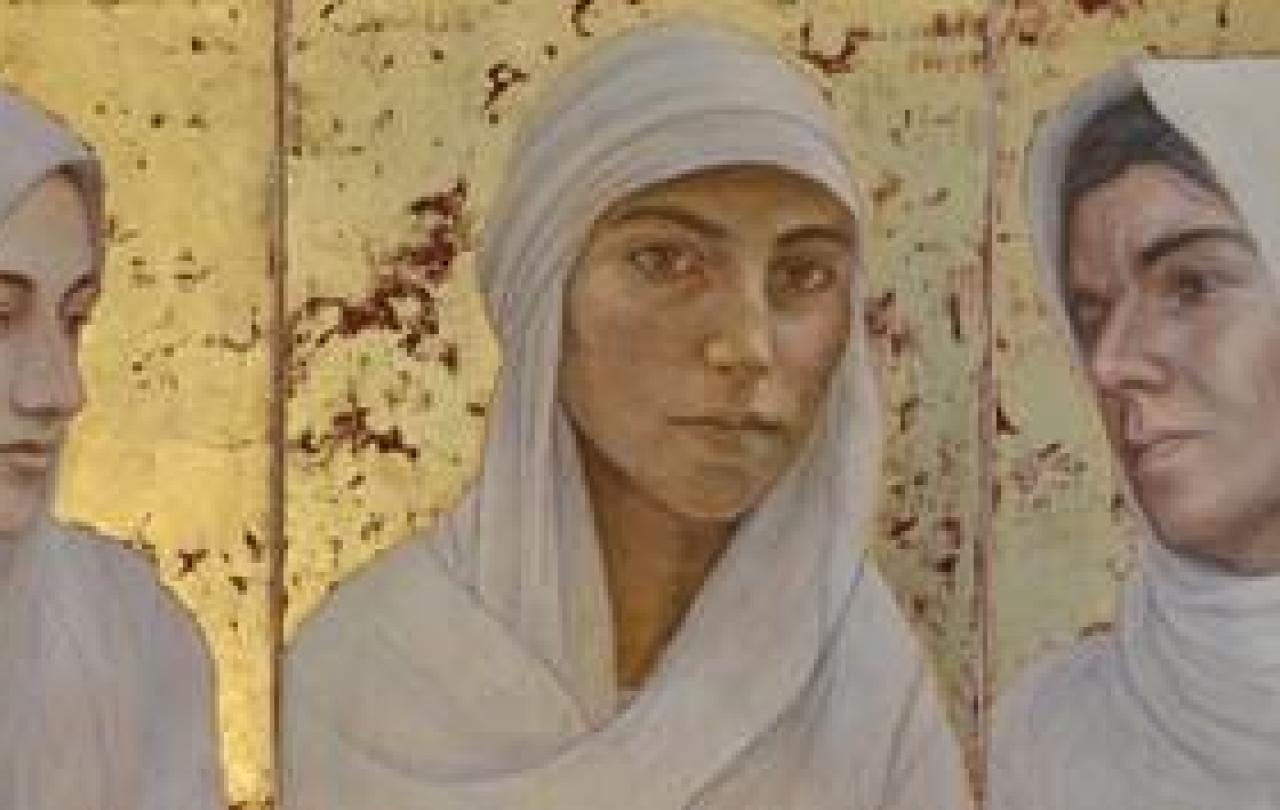

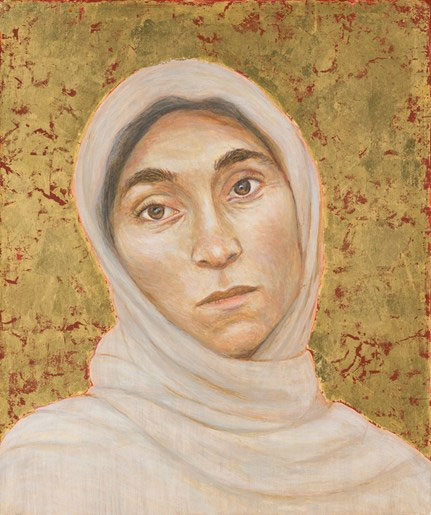

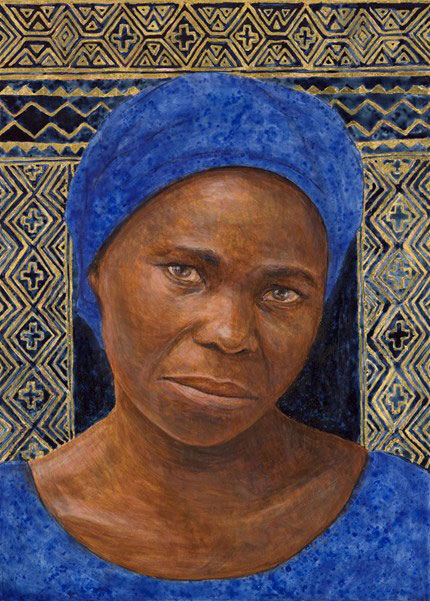

In March of this year on International Women’s Day, I was invited to attend the art exhibition and book launch of Tears of Gold by artist, Hannah Rose Thomas. Visceral and moving, the exhibition included both Hannah’s paintings and the self portraits of women survivors of ethnic and religious persecution, forced displacement and sexual violence; Yazidi women who escaped ISIS captivity in Iraq, Rohingya women who fled violence in Myanmar and Nigerian women who are survivors of Boko Haram and Fulani violence.

As I walked around the exhibition looking at the faces of thirty-three girls and women ranging in age from twelve to fifty years old, I saw faces that radiated dignity and resilience but also pain and grief that is beyond words. Most are looking away, but a few look straight ahead, their eyes locking with the eyes of the onlooker.

One was of Charity. As a woman myself, I felt an unexplained connection with this woman looking straight at me from the painting. She asked without words that I try to understand something of her suffering. Charity was held captive by Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria for three years and forced to “marry” one of her captors and convert from Christianity to Islam. She was raped and gave birth in captivity to a baby girl named Rahila. When Charity was eventually rescued from her ordeal and reunited with her husband in a camp for internally displaced people, her husband beat her and rejected her baby. Now on a daily basis, she faces abuse and isolation in the camp. Although she is no longer harmed by her perpetrators, she is still paying for their crimes.

Another, Basse. The raw pain in her eyes strikes me. At the time Hannah painted her in 2017, it was three years since Basse’s daughter (age six) had been taken by Daesh (ISIS) after their Yazedi community was attacked and displaced in Sinjar in Iraq. She had since found her daughter’s photo on a “marketplace” website of girls for sale. As a mother myself I can only just begin to comprehend her anguish as one mother to another we gaze at each other through the painting.

As works of art, the portraits are extraordinarily skillful and beautiful, but they are so much more than that. They offer a glimpse into the soul of women who have experienced the most unspeakable suffering. In the words of Prince Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, the former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, they are Hannah’s “witness statement” for and on behalf of thirty-three brave women survivors, as well as shining a spotlight on the issue of gender-based violence that affects millions of women (a staggering one in three according to UN Women) across the world today.

From refugee camps to Whitehall

When I caught up with Hannah recently, she spoke about the privilege of meeting these women during the trauma-healing art workshops she organised with support of local partners and the sponsorship of charities (including BRAC, Open Doors, World Vision and Bellwether International).

Starting out as an Arabic student in Jordan, she had her first opportunity to work with Syrian refugees for the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in 2014. She began to paint the portraits of some of the refugees to show the real people behind the statistics of the global refugee crisis. This first gave her a glimpse of the healing potential of the arts and how it can be used as a tool for advocacy. Since Jordan, she’s been able to organise art projects with Yazidi women who escaped ISIS captivity in Iraqi Kurdistan in 2017; Rohingya refugees in Bangladeshi camps and Christian women survivors of sexual violence at the hands of Boko Haram and Fulani militants in Northern Nigeria, both in 2018, and most recently with women from the asylum-seeking community in Glasgow and Ukrainian refugees in Romania.

Warm and immensely articulate, Hannah seems impossibly young, grounded and humble to have been on such a remarkable life journey already, from working with the women in the camps to exhibiting her paintings in numerous places of influence including the European Parliament, the British Houses of Parliament and Buckingham Palace, even meeting HRH King Charles and showing him her portraits of the Yazedi women.

She describes King Charles, who went on to write the foreword for her book, as “genuinely interested in the stories of the women and really touched by them.”

Easing the burden

Creativity and an interest in the power of the story has always fascinated Hannah since she was a child. And as she writes in the introduction to Tears of Gold, all her work has a common thread of intention, “the restoration of these women’s voices”. She longs to give them a unique platform to tell their stories and refers to Holocaust survivor Primo Levi who describes the “unlistened-to story” as the enduring burden of the survivor.

This desire to give a voice to the voiceless has dove-tailed in a surprising and powerful way with her love of creativity. She says,

“Ever since I was young I have…had this desire to be a voice for the voiceless somehow but never imagined this could be through art. For many years there has been this tension between these two aspects of myself – this longing to express something of the beauty of God through my paintings and yet another aspect compelled to work in the sphere of social justice and human rights. God has woven together these two separate strands in the most beautiful and unexpected way.”

Drawing on the writings of the French Philosopher Simone Weil, Hannah asks in her book:

“can the creative arts create a space to pay attention to the unspeakable suffering of another? Can this help restore her?”

She tells me about the privilege of seeing the transformative impact on some of the women in her workshops as she taught them to put brush to paper to paint their self-portraits as a way of telling their stories. Many of the women painted themselves with tears. What is striking is that the stories behind the art reveal survivors not victims. One young Nigerian women Aisha, who had suffered rape at the hands of Fulani militants, painted gold tears she said symbolised God bestowing on her a crown of beauty instead of ashes; the oil of joy instead of mourning. Her story is about being precious in God’s eyes and his restorative healing in the face of unimaginable human-induced suffering.

One girl who took part in the Nigerian art project, Florence, had been raped by Fulani militants when she was ten years old. On her last day at Hannah’s art project she said, “Here I have found peace of mind.” God using his healing hand through art.

Connecting through vulnerability

“I had been on my own journey through post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Painting has been an important part of my recovery journey and how I learned to find my voice again. This was one of the key motivations behind these art projects as I wanted to be able to bring this gift to others.”

The stigma that survivors of sexual violence face in their own communities when they return home is particularly painful. During the art project in Northern Nigeria, Hannah publicly shared about her own struggles, following a traumatic experience as a young woman, with survivors of rape by Boko Haram and Fulani militants. The women later reflected together that this vulnerability connected them as women and helped them realise that they were not to blame and need not be ashamed. It began to break the stigma and silence and to create a safe space of mutual trust so they could begin to share their experiences.

Hannah writes, “Sharing our stories enables us to connect, and reminds us that we have more in common than divides us”.

Most precious and in the image of God

Coming face to face with the portraits painted by Hannah, as the daughter of a Portuguese Catholic father, I recognised the likeness of the style, colour and reverence to the icon painting of Jesus that my parents have on their wall at home.

Drawing on Mother Theresa who talked about “seeking the face of God in everything, everyone, everywhere, all the time . . . especially in the distressing disguise of the poor,” Hannah’s portraits seek to revere each woman, to paint them with the love and devotion that God might. They remind us that they are all of exquisite value in God’s eyes.

Hannah’s expression lifts as she explains the methods of iconography that she studied and practiced in order to paint the women’s portraits and the palette she used. Gold leaf as a symbol of their sacredness to God regardless of what they have suffered, and lapis lazuli, the most expensive and illustrious blue pigment sourced from the mountains of Afghanistan and used by artists such as Michelangelo in the Renaissance period, unparalleled for its depth and richness and purity.

Each painting takes a long time to complete, around nine days, due to a layering process required to build up the colour in the natural pigments that are used, Hannah says:

“I'm interested in the quality of attention. And the contemplative prayerful aspect of the paintings. For me they're a form of prayer. Praying for each of the women I've met.”

She explains that the process of Byzantine painting is like a prayer. Starting with the under painting with all the dark colours, the background tone, and then slowly progressing on a journey, adding in highlights, from darkness to light. It’s “symbolic of the journey of the soul” she says.

And how are they received in the political corridors of power? Hannah pauses.

“The fact that it takes so much time. It’s different from a photograph. It invites people to contemplate in a way that's quite unique. In a place with such high pressure where there isn't much time to pause. It’s about creating space for contemplation. Where mentalities can shift. When you slow down and attend to the story.”

Impossible to measure the impact of such a shift, but when Hannah tells me about the number of politicians moved to tears by both the paintings and the women’s stories, it is clear the impact is there, measurable or not.

The art of attention

Tears of Gold opens with Hannah’s reflection on the art of attention. The word “attention” comes from the Latin ad tendere, meaning to reach towards. She writes:

“Only by reaching out in love and understanding can we overcome the agendas of violence and polarisation that seek to divide us.”

According to Rabbi Jonathan Sachs, this “reaching out” requires a commitment “to see in the human other a trace of the divine Other... to see the divine presence in the face of the stranger.”

When we reach out and allow ourselves to connect with the suffering of another whose pain is unimaginable – in Hannah’s words, to reach across the abyss of difference between us - we take a step towards understanding that suffering. Art can be a way of bridging that abyss, of opening a passage between us and the other. By taking a step towards the other and understanding just a fraction of their pain, we can be stirred.

Does the arts have the ability to stir us beyond the self-centred voyeurism that an overload of media imagery may have reduced human suffering to? By the way Hannah’s portraits have been received in the corridors of power in the Global North, we can only hope that the answer is yes.

Perhaps the arts are the answer to stirring humanity’s compassion to move beyond complacency.

And to demand a different way.

Tears of Gold by Hannah Rose Thomas can be purchased from Plough. All publisher profits from this book will be donated to relevant charities.