Over 100 million people in the world have fled their homes to escape persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, or some other threat to their life and safety. Known as forced migrants or displaced people, these people are unable to return for the same reason they left. Every year their number grows, so every year it is at a record high.

Does Christianity have anything to say about this global crisis? The answer to this question is a resounding ‘yes’. Although forced migration is a larger issue today than ever before, it has been a problem throughout human history, and the Christian tradition has a lot to say about it.

Be Clear about facts and definitions

A Christian response starts with the wisdom not to let sensationalist media dictate our understanding of the situation. We are frequently given an image of a deluge of immigrants arriving at our borders, an overwhelming quantity of people for which we do not have space or resources. But this image is not accurate.

Some countries in the world are indeed overwhelmed with refugees, but the UK is not even close to being one of them. The UK is not even in the top 25 host countries, and refugees make up only 0.2 per cent of our population. In fact, 83 per cent of the world’s refugees are in developing areas far less equipped to respond than any wealthy Western nation.

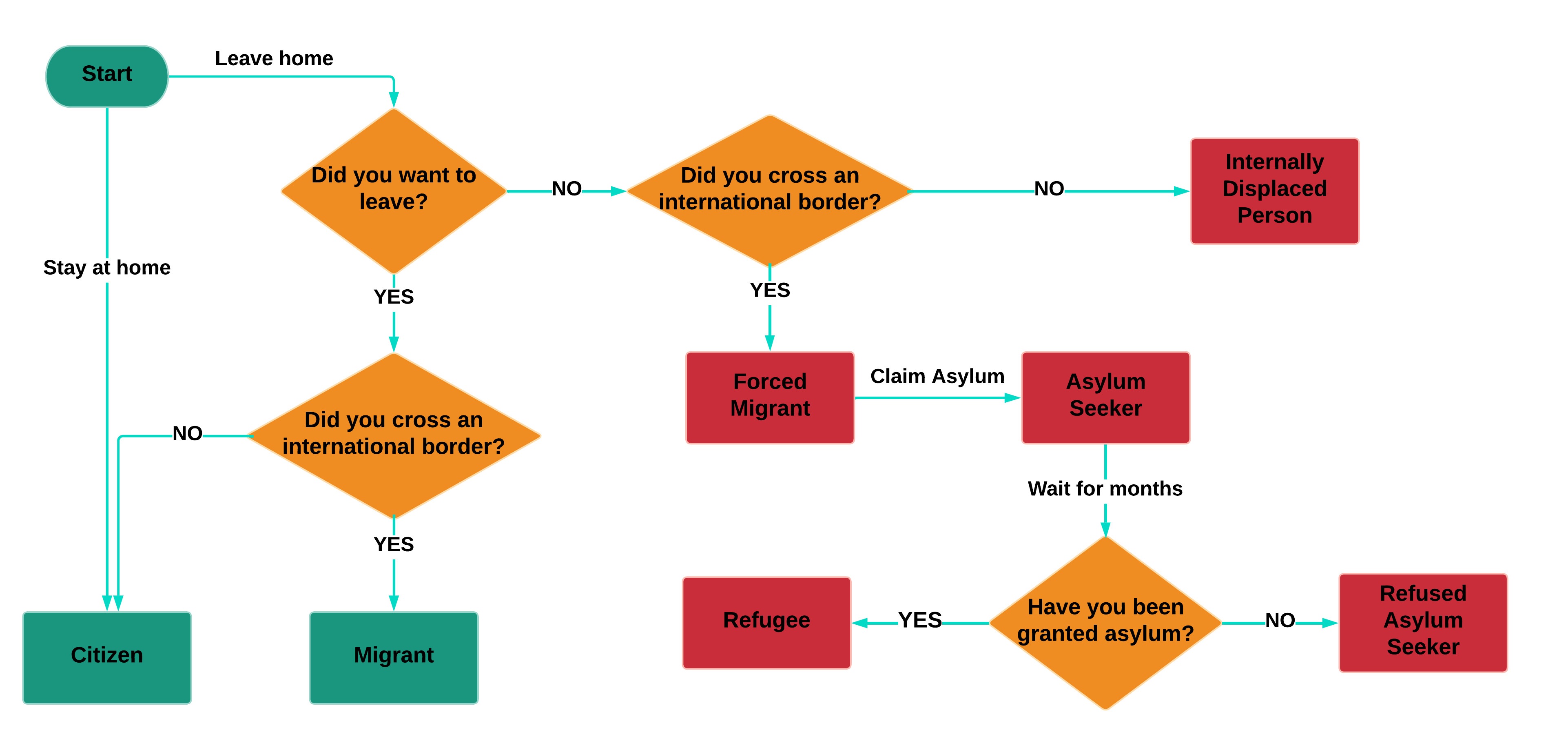

Learning the difference between an ‘asylum seeker’, a ‘refugee’, a ‘migrant’ etc. can also clear up a lot of confusion. Here’s some definitions that may help.

Citizen: someone who stays at home in their country.

Migrant: someone who has freely chosen to live in a country not their own.

Internally displaced person: someone who has been forced to leave their home to preserve their life or safety but has not crossed an international border.

Forced migrant: a displaced person who has crossed an international border.

Asylum seeker: a forced migrant who claims asylum in the nation they have entered.

Refugee: a forced migrant who has been granted asylum by the nation they have entered.

Refused asylum seeker: a forced migrant whose asylum claim has been rejected.

Yes, it is complicated. There’s even a flowchart to guide you through the various definitions.

Determining a migrant's status flowchart.

The situation in the UK is rapidly evolving and that chart may become out of date in the near future. There are moves by the government to make claiming asylum illegal or to remove people to Rwanda under certain circumstances. This chart also leaves aside the question of the legality/illegality of migration, a complication that would distract from the purpose of this article.

A command to welcome strangers

Throughout the Bible, displaced people are seen as one of the three most disadvantaged groups in society and most deserving of special care and compassion. Again and again, it enjoins special support for ‘orphans, widows, and strangers’ as those who are least able to support themselves. The reasons for this are obvious. If you are displaced, you have fled your home, earthly possessions, employment, and most likely your family, bringing with you only what you could carry. You have arrived in a foreign culture full of people who do not know you, have no familial or citizenship obligations to you, who may speak a different language, and who will almost certainly treat you with suspicion and distrust.

Because of this natural disadvantage, our obligation towards strangers is embedded deep in the law of the people of God. Here’s my translation of what’s said in an early book of the Bible, Leviticus:

‘When a displaced person [ger] moves to live among you, you shall not do them wrong. You shall treat them as the native among you, and you shall love them as yourself, because you were displaced people [gerim] in Egypt’.

Or in a later book, Numbers:

‘There shall be one statute for you and for the displaced person [ger] who lives among you, a statute forever throughout your generations. You and the displaced person [ger] shall be alike before the Lord. One law and one rule shall be for you and for the displaced person [ger] who lives among you.’

More than thirty times the Old Testament repeats the command to treat displaced people just as you would treat a native. This makes it one of the most frequently repeated commands in the whole Bible.

We are told to embrace and welcome ‘the other’, not because they are other, but on the basis of a prior sameness: we are all human beings created in God’s image.

Why such a huge emphasis? Undoubtedly because of the natural human tendency to do the opposite, to discriminate, to ostracize foreigners. Xenophobia, racism, and ethno-centrism are constant temptations. We are told to embrace and welcome ‘the other’, not because they are other, but on the basis of a prior sameness: we are all human beings created in God’s image. We all belong to the same category, participating in the same human form. Christianity knows that we need to be trained and constantly reminded to see otherness, not as a threat, but as part of the beautiful diversity of God’s good creation in which each of us uniquely reflects part of God’s image, and where the full image is only seen in all of us at once. Humanity is in the image of God more than any individual human.

Jesus himself fled his homeland to escape being killed. Moreover, the writer of the story underscores that this was not an accidental happenstance in Jesus’ life but a necessary fulfilment of prophecy. It was necessary that Jesus be displaced, just like it was necessary that he die and rise again in order to fulfil his mission. Jesus’ experience as a refugee identified him with all displaced people throughout history. To further emphasise the point and make sure we can’t possibly miss it, Jesus told a parable about the final judgment in which our salvation turns on whether or not we identify him with the displaced.

“Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.”

There’s no question here about the overall attitude towards strangers that Christian faith enjoins upon its members. But commands are not the main way God communicates. This is because commands rarely get to the heart of why we behave a certain way, and they do not have the power to change the motivations of our hearts. Christian faith wants us to love and welcome strangers, not because we ought to, but because we want to, because we can see how it enriches our lives and communities. So why don’t we want to welcome the displaced? That is the more important question.

The reality is that welcoming strangers does make us vulnerable. It may interfere with our comfortable lifestyles, and it may refashion normal British life in unexpected ways.

I said earlier that ‘treat the displaced person like the native’ was one of the most frequent commands in the Bible. But ‘don’t be afraid’ is the most frequent command by far. It’s one we need to hear when considering the welcome of strangers. The media has made a scapegoat out of migrants in recent years, just like it used to scapegoat Jewish people and other ‘others’ at various points in history. As a result, much of the UK population is primed to treat non-natives with suspicion. We are terrified of being overwhelmed by foreigners invading our communities, terrorising our neighbourhoods, and changing culture beyond recognition.

These fears are vastly overblown, but they do not come from nowhere. The reality is that welcoming strangers does make us vulnerable. It may interfere with our comfortable lifestyles, and it may refashion normal British life in unexpected ways. It will certainly involve some sacrifice of things we are used to and enjoy. But Jesus never promised that the path of virtue would be easy, comfortable or risk-free. What he promised is that it would be worth it, and that he would take care of all the areas that really matter (to which wealth, comfort, and nostalgia about changing culture do not belong).

“Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing? … But strive first for the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well.”

If our words or actions are based out of fear, then we are not alone. But fear cannot be the basis for our decisions. Letting go of fear and radically following Jesus no matter what the cost will take us on a great adventure – the adventure we were created to be on.

What does that adventure look like? In our own age, God has given us the task of enriching our lives and diversifying our culture by welcoming Jesus in the form of the stranger.

Take practical steps forward

What can be done by an ordinary Christian in an ordinary church in the UK?

There is so much that can be done both at the political level with immigration law and at the local level with the refugees already among us. The best place to start is to get in touch with one of the amazing charities who already work in this area, let them educate you about the issues, and offer financial and/or volunteer support.

-

Jesuit Refugee Service is one of the largest and longest-standing refugee charities. Backed by decades of experience and expert scholarly research, they do all kinds of work not only with refugees but with detained asylum seekers and those who have been refused asylum.

-

In Manchester you could get in touch with the Boaz Trust who do fantastic work with all kinds of displaced people. Their founder also wrote a powerful book that is well worth a read.

-

Refugee Education UK is always looking for volunteers to work with young people towards a hopeful future through providing greater access to education.

-

Welcome Churches seeks to build a network of equipped and educated Christians around the nation who can rapidly welcome new refugees and asylum seekers as soon as they arrive in a new town or city.

-

Christian Concern for One World offers a rich spread of resources to educate, inform, and network anyone who cares about working with the displaced.

All these charities will put your time and money to good use, as well as introducing you to refugees you can serve and benefit from building a relationship with. Go!

FAQs

Your definition of ‘refugee’ doesn’t explain how the government decides who to grant asylum to. What is the government’s basis for giving someone refugee status?

The UN holds its members to a definition of a refugee that was laid down by the 1951 Refugee Convention. This convention determined that a refugee is someone who, ‘owing to a well‐founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.’ For someone to claim asylum triggers a process whereby a nation determines whether or not that person can justifiably be said to fit that definition. There are many problems with this definition and most experts on refugee studies are unhappy with it for various reasons, but it is extremely difficult to establish a consensus on a new one.

Why did you translate the Hebrew word ger as ‘displaced person’?

Ger is one of four Hebrew words for foreigner. Nokri means any foreigner; zar means (roughly) someone not part of your group; toshav means a passing traveller or hired worker and sometimes a slave. There is some discussion over what the term ger means, but the growing consensus is that this refers to a displaced person. It’s certainly clear from the context in which the word is used that the person under discussion is unable to provide for themselves and lacks access to basic resources, and for a foreigner displacement is the most likely reason for this. For more information, check out Mark Glanville’s book, Adopting the Stranger As Kindred in Deuteronomy (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2018).