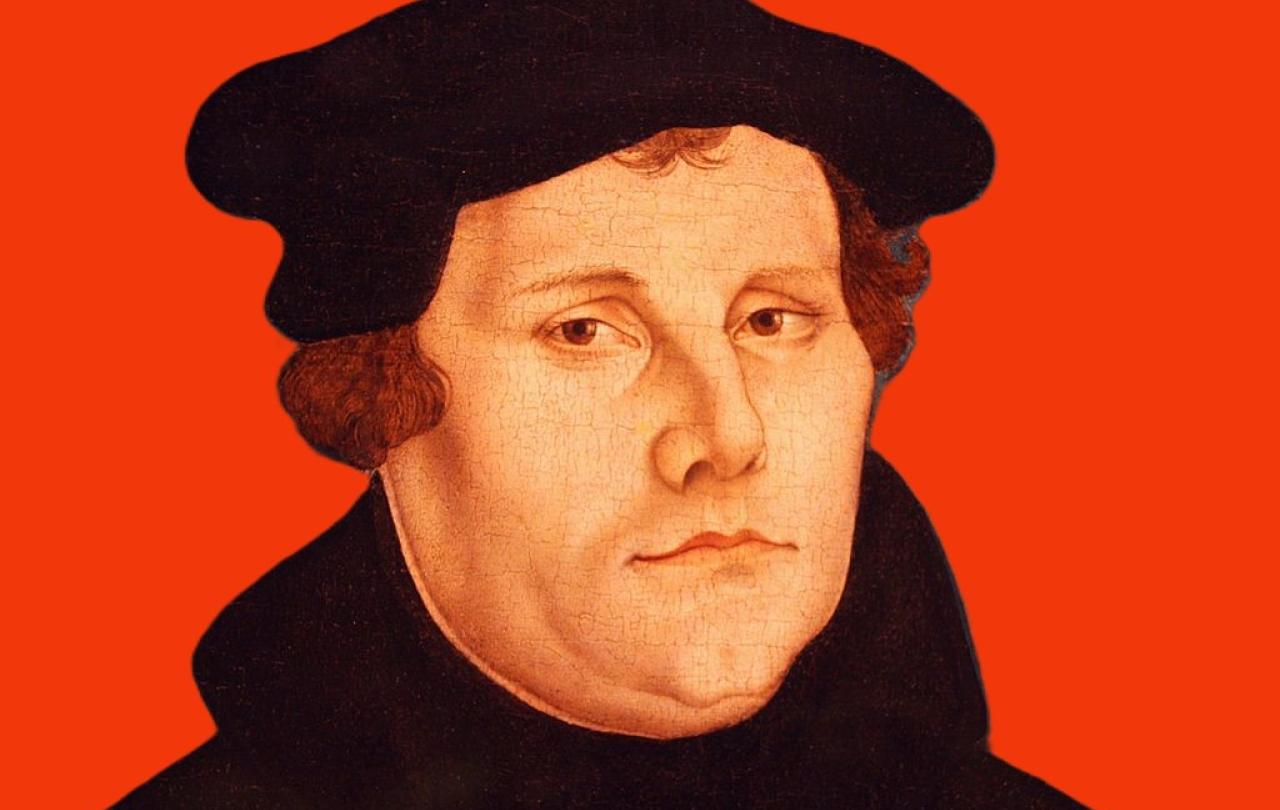

Tensions build as the German election approaches. Money is flowing, bargaining going on behind the scenes. (We are talking the election of 1519 here). There is the favorite, Karl—they called him Carlos in the Spanish dominions he had inherited from his maternal grandparents, Ferdinand and Isabella—, grandson of the German emperor, Maximilian of Austria, and there is the challenger, the King of France, Francis I, and there is the wild card, the duke of Saxony, one of the seven electors who would elect the next emperor, Frederick, called the Wise. Frederick had no imperial ambitions, and he tipped the election to his distant cousin, the then young man we call Charles V. Two years later, that gave Frederick the leverage to win a hearing for his most prominent professor at the pride of his heart, his new university in Wittenberg, Martin Luther.

Charles regarded this Augustinian friar, who had been excommunicated at the beginning of 1521 by Pope Leo X, as a dangerous heretic. He wanted to declare Luther a criminal, open for execution on the open road by whoever might find him and run him through. Frederick advised the young emperor not to treat a German subject like that, so Charles arranged for Luther to come to the imperial diet in Worms in May 1521 to recant. Luther explained to the emperor that he really could not recant since his writings contained many truths. He continued, “I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted, and my conscience is captive to the Word of God.” Later reports say that he added the words, “I cannot do anything else. Here I stand. God help me!” Whether he said “here I stand” or not, that is what Martin Luther did at Worms and continued to do for the next quarter century until his death.

Upon what was he standing? As a “doctor in Biblia,” a “teacher of the Scriptures,” Luther had taken up the latest methods of the so-called humanist movement for exploring ancient texts in their original languages. Jurists turned to Justinian’s Code in sixth century Latin. Physicians were reading Galen’s medical advice in ancient Greek. Theologians immersed themselves in the Bible in Hebrew and Greek. Luther had put the tools of these methods to use as he lectured in the 1510s on the Hebrew Psalms, and then the apostle Paul’s letters to the Romans and to the Galatians. There he found a new way of viewing himself, the God whom he found speaking to him in the pages of the Bible, and his fellow human creatures. He used the world “righteousness” in the way we might use “personal identity” today. He heard from the biblical writers a different way of identifying who he was at his core by listening to God’s regard for him.

Just as our DNA is a gift, not something we have to work to earn, so Luther’s core identity came from outside himself.

Luther certainly did not deny that human performance helps give each human being a variety of identities as we go about what he saw as callings from God in our exercise of responsibilities in our homes, in our economic life, in our societal networks and political structures. He believed that in these spheres of life we are active in shaping the way other people view and identify us. But at his core, Luther found the person behind the masks of his everyday life to be unable to perform everything that would make him the good person he wanted to be, the good person he thought God wanted him to be. Just as our DNA is a gift, not something we have to work to earn, so Luther’s core identity came from outside himself. It came as a gift from God, his Creator. He received it passively, and his trust in the God who gave him this passively bestowed identity set his entire life in order. Because he trusted God to be his support and to justify who he was, he felt freed to perform his responsibilities toward other human creatures actively.

Luther believed that on his own he had not been able to trust God, to love him and give him proper respect. Like the modern psychiatrist and philosopher, Erik Erikson, Luther believed that trust forms the basis of human personhood and personality. He saw that his trusting some Absolute and Ultimate formed his character and enabled him to function as a human being. He recognized in the God presented by the Old Testament prophets of Israel and the New Testament evangelists and apostles the ultimate and absolute person, who approached the human creatures who had turned their backs on him by becoming one of them as Jesus of Nazareth. In the mysterious ways of the Creator, Jesus’s death covered the transgressions and offenses, the mistakes and failures, of all human beings, and in his resurrection God gave new life, a new identity, true righteousness to those who trust in him.

Luther found that message liberating. It freed him from being imprisoned in a cycle of always insufficient attempts to be the person he wanted to be to please his Creator. He rested in the unconditional love of this Creator, who had come face to face with humankind as the rabbi from Nazareth, crucified but back from death itself. That freed Dr. Luther to be bonded to those within his reach who needed his care and love. He need not manipulate them by doing them the good he needed to make himself look good in God’s sight and feel satisfied with himself. He now could do them the good that they truly needed. That gave his tempestuous spirit a sense of joy and peace.

He lived out a rather peaceable life under the ban of church and empire, but safely ensconced in the lands of his Saxon electors. Family life brought him much joy. His judgment that God had given human beings the gift of sexuality for companionship and support as well as procreation made him uncomfortable with his own vows of celibacy, but not so uncomfortable that he would have married had not a nun named Katharina von Bora, who had left the cloister, laid claim to him. Together they created a bustling household with their six children being raised in the cloister where Martin had lived as an Augustinian Brother, large enough to house students and guests from places far from Wittenberg. Katharina served as his counsellor and theological conversation partner as well as the efficient manager of this ever-changing parade of co-inhabitants of their home.

Music filled their home. Luther’s firm tenor voice and his lute and his flute led family and visitors in evenings of song, sometimes giving voice to hymns he had written. His sense of tone and rhythm coupled with sensitivity to the fine points of spoken and written speech made him a scholar of great skill and a translator who “looked into the mouths” of the people in the marketplace and render the Bible in their tongue. His curiosity stimulated or at least supported colleagues at the university across the disciplines, including a botany instructor who took students the woods to look at leaves and colleagues in mathematics and astronomy who were playing with the new calculation of the heavens by Nikolaus Copernicus.

Luther’s lively engagement with life and his dramatic search for peace in the pages of the Bible produced a man who enjoyed life despite his struggles with “melancholy,” a widespread disease of his time, and the threats of violence to his person that never disappeared. His robust wrestling with the biblical texts provides even today stimulating, even provocative reading for anyone, who is looking for the heart of the matter, the matter of self and life.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief