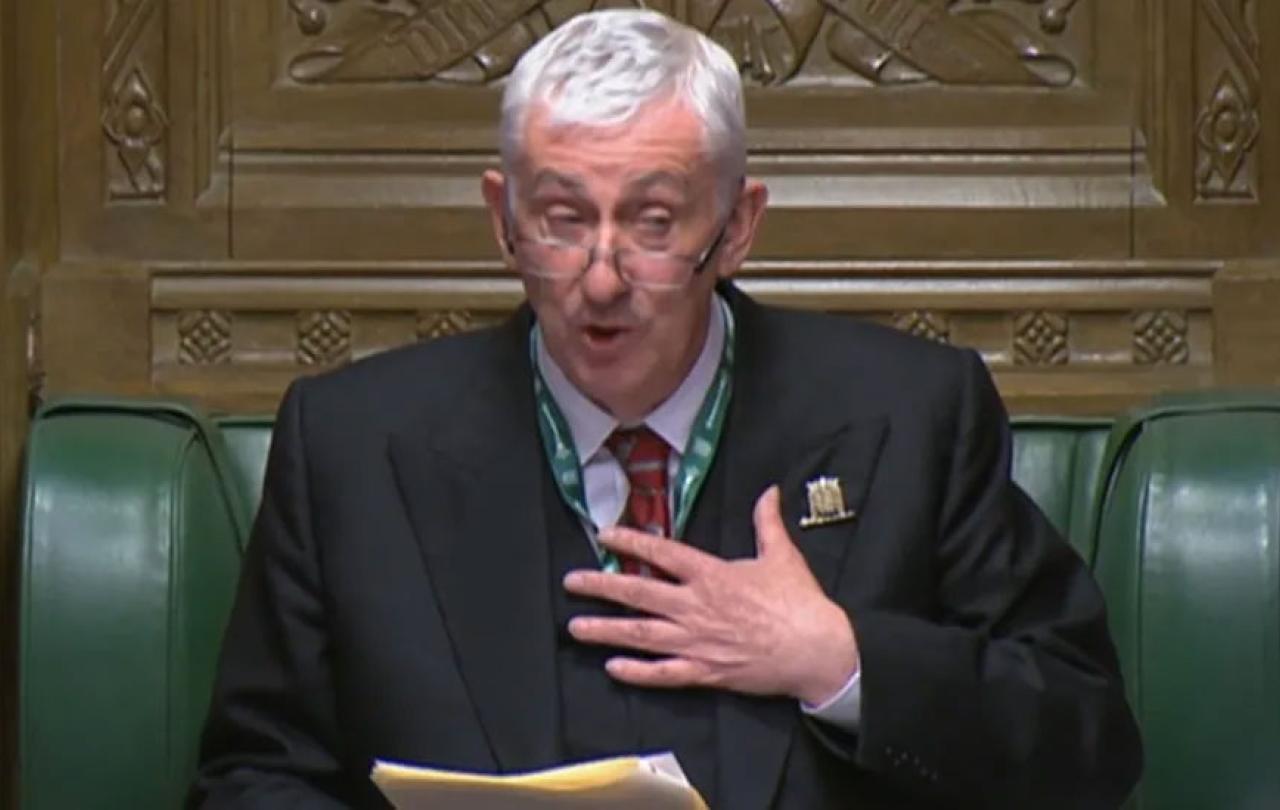

“Nearly a quarter of a century has passed since a speaker of the Commons stood down from its high chair with dignity and to applause.” Thus wrote Andrew Rawnsley in the Guardian this Sunday. Last week the House of Commons erupted. An unedifying lava-spew of recrimination and anger flowed through the corridors of power as the Speaker of the House, The Right Honourable Sir Lindsay Hoyle, broke parliamentary convention to the seeming benefit of the Labour Party. Memories of his predecessors’ playing fast-and-loose with Parliamentary procedure pushed buttons. The SNP’s Gaelic fury founded a flurry of calls for the Speaker to step-down, and it was not until he gave a near-tearful apology that some calm seemed to be restored. Opponents cried foul - ‘how dare he upend the conventions of the House!?’ - while supporters jumped to his aid - ‘he was just trying to protect MPs from further harassment over the Israel-Gaza debate!’ - and everyone was unhappy…

The technicalities of this convention (that multiple amendments are not called upon for voting during an Opposition Day Debate) are less interesting to me than the fact that the convention exists. ‘Convention’ is another word for ‘tradition’. Traditions are important. Our famously ‘unwritten’ Constitution relies heavily on tradition, especially for the smooth running of Parliament. Rather than having the process of legislating and governing micro-managed with procedural minutiae, the Commons operate on the basis of nurturing and conforming to its traditions. In essence, the House of Commons operates on the basis of respect - by respecting the traditions of the House, Parliamentarians grow to respect each other as fellow followers of tradition. Exterior action builds-up interior disposition. Practice influences sentiment.

At least, that’s my romantic take on it. Traditions give some coherence to a society - from the society of elected MPs right through the society of a nation - and allow it to flourish. Traditions bind people together. Traditions unite. You may come from a different part of the country than your neighbour, have different family values, have a different religion or skin-colour or education-level, etc…but you can be united in the traditions you follow. Whether it’s having a roast on a Sunday, going to a Carol Service in December, singing Three Lions in a World Cup year, the traditions you share despite all other differences give you a common cause with those around you.

This is not to say that traditions can’t have a dark side. Some traditions can alienate guests. Some traditions can stifle creativity and innovation. Some traditions can be maintained purely to bamboozle the uninitiated for the benefit of those in the know. In extremis, some traditions can lead to groupthink, to the othering of those who don’t share them, to jingoism and hatred; St Paul wrote that it was the zeal for the traditions of his fathers than led him to persecute the first Christians. Traditions should never be taken for granted or left unexamined. Traditions are roses - beautiful and sweet-smelling, but always in need of pruning. But let the gardener prune carefully - you want some roses left for the garden.

When the scribes and Pharisees try to trick and trap Jesus with impossible thought experiments, they often quote their traditions. Jesus always wins the debate. He wins in the face of their traditionalism. He wins by being a radical. RADICAL! His radicalism is not marked by the abandonment of the concept of tradition, but by deep respect for it. The Sermon on the Mount is probably the most famous speech about the importance of tradition - “You have heard that it was said to those of ancient times…But I say to you…” - keeping the traditions of God in the face of the self-serving traditions of men. The scribes and the Pharisees are the White Witch to Jesus’ Aslan: ‘“It means,” said Aslan, “that though the Witch knew the Deep Magic, there is a magic deeper still which she did not know. Her knowledge goes back only to the dawn of time.”’

Not every critic last week will have genuinely cared about the traditions of the House of Commons. Many will have mouthed the words but would have happily stood by if the breaking of convention benefited them. Nevertheless, we must take tradition, and it’s breaking, seriously. Traditions nurtures the relationships of MPs. Traditions nurture the relationships of neighbours and fellow citizens. Traditions nurture relationship with God, as the traditional rhythms of religious practice and Church seasons help order prayer and worship. Perhaps we’ll look back on the upturning of this particular Commons tradition and recognise it as the right rejection of an outdated convention…but let's be cautious. Traditions are important. Break them with care.