Julian of Norwich doesn’t seem to tick many boxes as an ‘influencer’, but her (yes her!) quietly revolutionary theology has had an impact that would probably startle her considerably. For example, TS Eliot quotes her in Little Gidding as he explores the delicate and unexpected grounds of hope. Julian’s striking mixture of confidence and hiddenness lend themselves well to Eliot’s meditative poem.

Her anonymity is part of what draws us to her now. She opens a window into a world where women were largely unheard and uncelebrated.

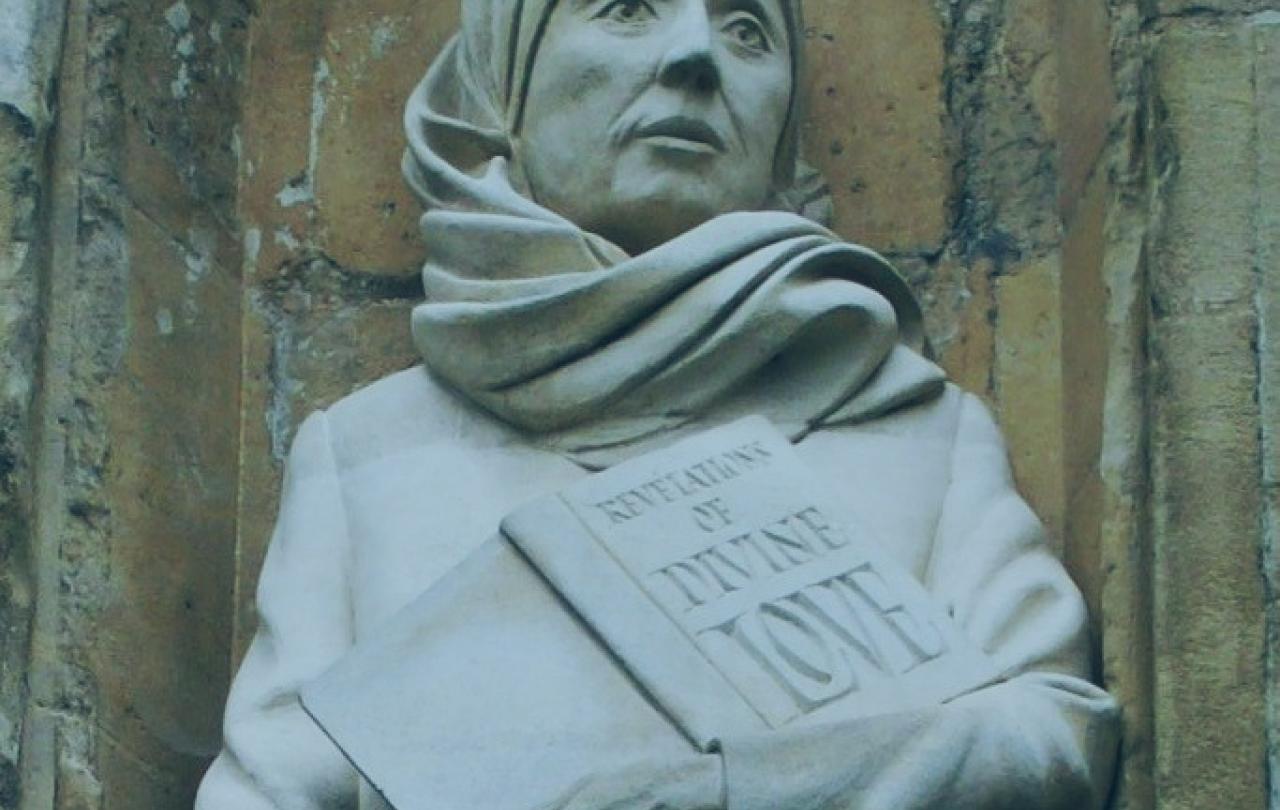

It’s unusual to claim authority for someone whose name we don’t even know. She is almost certainly named after the church of St Julian in Norwich, in which she spent years, walled up so that she could see into church, and talk to people through a little window, but never leave. But her anonymity is part of what draws us to her now. She opens a window into a world where women were largely unheard and uncelebrated. We hear so few women’s voices from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries – or indeed, for several centuries before and after. Julian tells us that she was ‘uneducated’, by which she probably meant that she didn’t read or write Latin, which was the cultured language of the day. Instead, she wrote what is probably the first book by a woman in English.

Her modesty about her educational background also gives her the freedom to write about God without having to worry about being theologically correct. She describes a series of visions that she received from God. She makes no claim for the doctrinal purity of what she understood, so she never got into trouble, despite the fact that she describes God’s attitude to us in ways that would not have met with approval by the Church authorities of her day. From what God showed her in her visions, although human sin and failure is real, it is not final, and God does not judge us for it, because it is already overcome through Jesus’ identification with us.

‘Sin is necessary, but all shall be well and all things shall be well and all manner of things shall be well’,

she writes. This is not blind optimism, but based on her experience of the character of God that she sees in Jesus. As far as Julian can see, Jesus doesn’t blame us for our sin. She isn’t necessarily assuming that everyone will be saved, but she is sure that God doesn’t seek to judge us.

She lived through the Black Death. Like so many of us now, she must have suffered bereavement; indeed, the visions she describes were shown to her while she lay on what everyone assumed was her own death bed. Some experts think she may have been widowed and lost children, because of the way in which she writes about Jesus’ maternal qualities. Her message of the invincible, trustworthy love of God is even more challenging against the background of fear, loss and death, and it springs from her encounter with the crucified Jesus. She tells us that as she lay dying, a priest held a crucifix before her eyes, and she saw the figure on the cross as real and in agony. But she also saw that Jesus hangs on the cross out of his own free will, so that no one can doubt the love of God. This act of suffering identification with us is the source of hope, Julian says, because both Jesus’ suffering and his victory over death are real.

She spent the rest of her life pondering what she had experienced, interrogating it for meaning, going back to God to ask for further clarification.

Julian also has a lot to teach us about what to do with our experience of God. On first reading, it seems that she is wholly experiential in her approach, but then we discover that she spent the rest of her life pondering what she had experienced, interrogating it for meaning, going back to God to ask for further clarification. The longer version of her manuscript was probably written twenty years after she first received the visions. She trusted her experience, but she also thought she needed to work at it and be patient with it and dig more deeply into what it meant.

What I really want to do now is quote all my favourite bits of her book, The Revelations of Divine Love, but that would be a spoiler. Read her for yourself, but don’t be lulled by her gentle, narrative voice into missing her theological daring and passion.

Recommended further reading

You can read Revelations of Divine Love online.

Or buy the book from Oxford World’s Classics, OUP, 2015.

There are so many books about Julian, try:

Philip Sheldrake, Julian of Norwich – “In God’s Sight” – her theology in context (John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2018).

Denys Turner, Julian of Norwich, Theologian (Yale University Press, 2011).