The UK’s global artificial intelligence (AI) conference is nearly upon us. If the UK had a ‘prophecy office’ it would have issued a yellow or even amber warning for the first days of November by now. Prophecy used to be a dangerous business, the ancient text of Deuteronomy sanctioned death for false prophets, equating its force with a leading away from God as the ultimate ground of truth. But risks duly acknowledged, here is a prophecy about the prophecies to come. The global AI conference will loudly proclaim three core prophecies about AI.

- This time it’s different. Yes, we said that before but this time it really is different.

- Yes, we need global regulation but, you know, it’s complicated so only the kind of regulation we advise is going to work.

- Look, if we don’t do this someone else will. So, you should get out of our way as much as you possibly can. We are the good guys and if you slow us down the bad guys will win.

I feel confident about this prediction not because I wish to claim the office of prophet but because just like Big Tobacco and Big Oil, Big Tech’s lobbyists will redeploy a tried and tested playbook. And here are the three plays at the heart of it.

Tech exceptionalism. (We deserve to be treated differently under the law.)

Regulatory capture. (We got lucky, last time, with the distinction between platform and publisher that permitted self-regulation of social media, the harvesting of personal data and manipulative design for attention, but the costs of defeating Uber in California and now defending rearguard anti-trust lawsuits means lesson learned, we need to go straight for regulatory capture this time).

Tech determinism. (If we don’t do it, someone else will. We are the Oppenheimers here.)

Speaking of Pandora

What should we make of these claims? We need to start by exploring an underlying premise. One that typically goes like this “AI is calling into question what it means to be human”.

This premise has become common currency, but it is flawed because it is too totalising. AI emphatically is calling into question a culturally dominant version of human anthropology – one specific ‘science of humanity’. But not all anthropologies. Not the Christian anthropology.

A further, unspoken, premise driving this claim becomes clearer when we survey the range of responses to the question “what does the advent of what the government is now calling ‘frontier’ AI portend?”

Either, it means we have finally prized open Pandora’s box; the last thing humans will ever create. AI is our Darwinian evolutionary heir, soon to make us homo sapiens redundant, extinct, even. Which could happen in two very different ways. For some, AI is the vehicle to a new post-human eternal life of ease, roaming the farthest reaches of the universe in disembodied digital repose. To others, AI is now on the very cusp of becoming abruptly and infinitely cleverer than us. To yet others, we are too stupid to avoid blowing ourselves up on the way to inventing so-called artificial general intelligence.

Cue main global summit speaking points…

Or,

AI is just a branch of computing.

Which of these two starkly contrasting options you choose will depend on your underlying beliefs about ‘what it means to be human’.

Universal machines and meat machines

Then again, what does it mean to be artificially intelligent? Standard histories of AI always point to two seminal events. First, Alan Turing published a paper in the 1930s in which he proposed a device called a Universal Turing Machine.

Turing’s genius was to see a way of writing a type of programme to control a computer’s underlying binary on/off in ways that could vary depending on the task required and yet perform any task a computer can do. The reason your computer is not just a calculator but an excel spreadsheet and a word processor and a video player as well is because it is a kind of Universal Turing Machine. A UTM can compute anything that can be computed. If it has the right programme.

The second major event in AI folklore was a conference at Dartmouth College in the USA in the early 1950s bringing together the so-called ‘godfathers of AI’.

This conference set the philosophical and practical approaches from which AI has developed ever since. That this happened in America is important because of the strong link between universities, government, the defence and intelligence industry and the Big Tech Unicorns that have emerged from Silicon Valley to conquer the world. That link is anthropological; it is political, social, and economic and not just technical.

Let’s take this underlying question of ‘what does it mean to be human?’ and recast it in a binary form as befits a computational approach; ‘Is a human being a machine or is a human being an organism?’

Cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett was recently interviewed in the New York Times. For Dennett our minds and bodies are a “consortia of tiny robots”. Dennett is an evolutionary biologist and a powerful voice for a particular form of atheism and its answer to the question ‘what does it mean to be human?’ Dennett regards consciousness as ephemera, a by-product of brain activity. Another godfather of AI, Marvin Minsky, famously described human beings as ‘meat machines.’

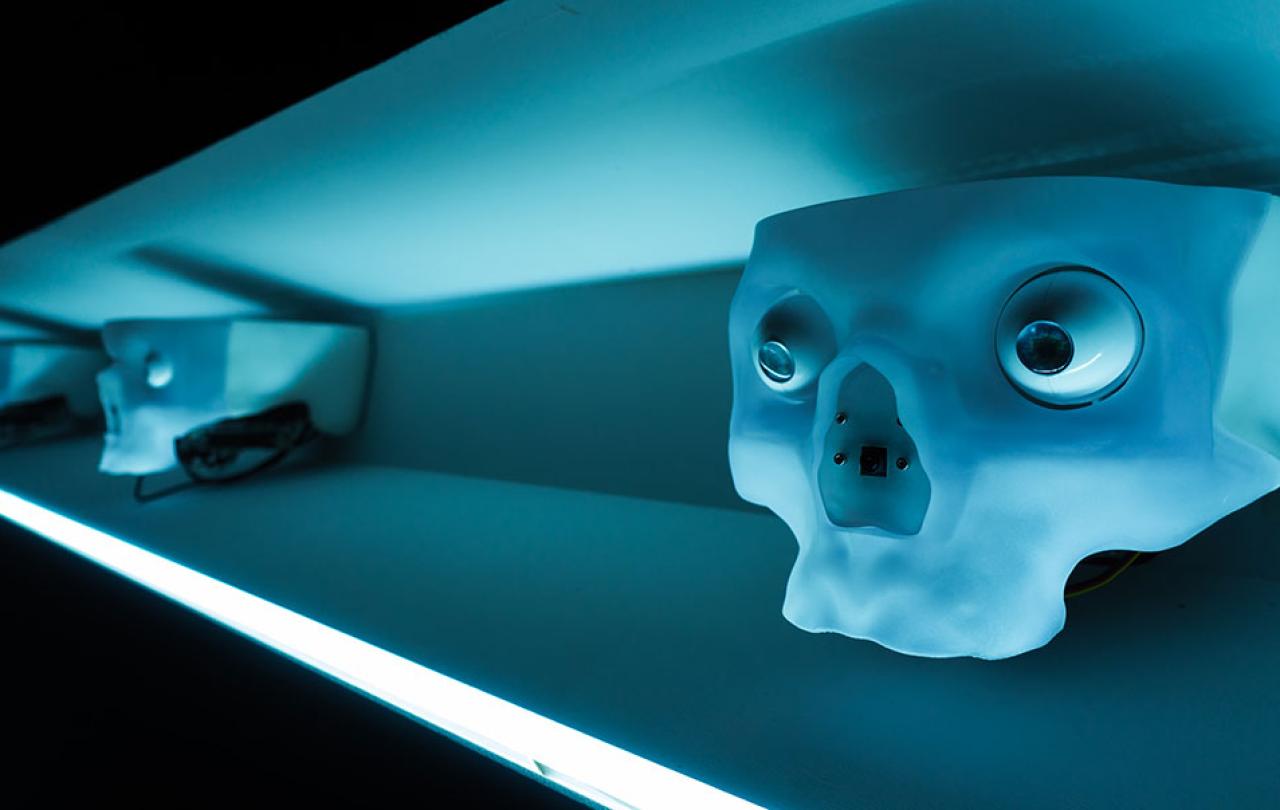

By contrast, Joseph Weizenbaum was also one of the early computer pioneers in the 1960s and 1970s. Weizenbaum created one of the first ever chatbots, ELIZA– and was utterly horrified at the results. His test subjects could not stop treating ELIZA as a real person. At one point his own secretary sat down at the terminal to speak to ELIZA and then turned to him and asked him to leave the room so she could have some privacy. Weizenbaum spent the latter part of his professional life arguing passionately that there are things we ought not to get computers to do even if they can, in principle, perform them in a humanlike manner. To Joseph Weizenbaum computers were/are fundamentally different to human beings in ways that matter ineluctably, anthropologically. And it certainly seems as if the full dimensionality of human being cannot yet be reduced to binary on/off internal states without jettisoning free will, consciousness and transcendence. Prominent voices like Dennett and Yuval Noah Harari are willing to take this intellectual step. Their computer says ‘no’. By their own logic it could not say otherwise. In which case here’s a third way of asking that seemingly urgent and pressing question about human being;

“Are we just warm, wet, computers?”

The immanent frame

A way to make sense of this, for many people, influential and intuitively attractive meaning of human being is to understand how the notion of artificial intelligence fits a particular worldview that has come to dominate recent decades and, indeed, centuries.

In 2007 Charles Taylor wrote A Secular Age. In it he tracks the changing view of what it means to be human as the Western Enlightenment unfolds. Taylor detects a series of what he calls ‘subtraction stories’ that gradually explain away the central human experience of transcendence until society is left with what he calls an ‘immanent frame’. Now we are individual ‘buffered selves’ insulated by rational mind so that belief in any transcendent reality, let alone God, is just one possible choice among personal belief systems. But, says Taylor, this fracturing of a shared overarching answer to the question ‘What does it mean to be human’ over the past, say, 500 years doesn’t actually answer the question or resolve the ambiguities. Rather, society is now subject to what Taylor calls ‘cross pressures’ and a lack of societal consensus about the answers to the biggest questions of human meaning and purpose.

In this much broader context, it becomes easier to see why as well as how it can be the case that AI is either a profound anthropological threat or just a branch of computing – depending on who you talk to…

The way we describe AI profoundly influences our understanding of it. When Dennett talks about a ‘consortia of tiny robots’ is he speaking univocally or metaphorically? What about when we say that AI “creates”, or “decides” or “discovers” or ‘seeks to maximise its own reward function’. How are we using those words? If we mean words like ‘consortia’ or ‘choose’ and ‘reward’ in as close to the human sense as makes no difference, then of course the difference between us and our machines becomes paper-thin. But are human beings really a kind of UTM? Are UTMs really universal? Are you a warm wet computational meat-machine?

Or is AI just the latest and greatest subtraction story?

To say AI is just a branch of computing is not to say the harms of outsourcing key features of human being to machines are trivial. Quite the opposite.

How then should we judge prophecies about AI emanating from this global conference or in the weeks and months to follow? I suggest two responses. The first follows from my view of AI, the other from my view of human being.

Our view of current AI should be clear eyed, albeit open to revision should future development(s) so dictate. I am firmly on the side of those who, without foreclosing the possibility, see no philosophical breakthrough in the current crop of tools and techniques. These are murky philosophical waters but clocks don’t really have human hands now do they, and a collapsed metaphor can’t validate itself however endemic the reference to the computational theory of mind has become.

Google’s large language model, Bard, for example, has no sense of what time it is where ‘he’ is, let alone can freely choose to love you or not, or to forgive you if you hurl an insult at ‘him’. But all kinds of anthropological harms already flow from the unconscious consequences of re-tuning human being according to the methodological image of our machines. To say AI is just a branch of computing is not to say the harms of outsourcing key features of human being to machines are trivial. Quite the opposite.

Which brings me to the second response. When you hear the now stock claim that AI is calling into question what it means to be human, don’t buy it. Push back. Point out the totalising lack of nuance. The latest tools and techniques of AI are calling a culturally regnant but philosophically reductive anthropology into question. That much is definitely true. But that is all.

And it is important to resist this totalising claim because if we don’t, an increasingly common and urgent debate about the fullness of human being and the limitations of UTMs will struggle from the start. One of the biggest mistakes I think public theology made twenty-some years ago was to cede a normative use of language that distinguished between people of faith and people of no faith. There is no such thing as being human without faith commitments of one kind or another. If you have any doubt about this, I commend No One Sees God: The Dark Night of Atheists and Believers by Michael Novak. But the problem with accepting the false distinction between ‘having faith’ and having ‘no faith’ is that it has allowed the Dennetts and Hararis of this world to insist that atheism is on a stronger philosophical footing than theism. After which all subsequent debate had, first, to establish the legitimacy of faith per se before getting to the particular truth claims in, say, Christianity.

What it means to be human

I see a potentially similar misstep for anthropology – the science of human being – in this new and contemporary context of AI. Everywhere at the moment, and I mean but everywhere, a totalising claim is being declared ever more loudly and urgently: that the tools and techniques of AI are calling into question the very essence of human identity. The risk in ceding this claim is that we get stuck in an arid debate about content instead of significance; a debate about ‘what it means to be human’ instead of a debate about ‘what it means to be human.’

This global AI summit’s proclamations and prophecies need to be placed in the right philosophical register, because to be human in an age of AI still means the same thing it has for millennia.

Universals like wonder, love, justice, the need for mutually meaningful relationships and a sense of purpose, and so too personal idiosyncrasies like a soft spot for the moose are central features of what it means to be this human being.

Suchlike are the essential ingredients of the ‘me’ that is reading this article. They are not tertiary. Perhaps they can be computationally mimicked but that does not mean they are, in themselves, ephemeral or mere artifice. In which case their superficial mimicry carries substantial risks, just as Joseph Weizenbaum prophesied in Computer Power and Human Reason in the 1970s.

Of course, you may disagree. You may even disagree in good faith, for there are no knockdown arguments in metaphysics. And in my worldview, you are free to do so. But fair warning. If the human-determinism of Dennett or the latest prophecies of Harari are right, no credit follows. You, and they, are right only because by arbitrary alignment of the metaphysical stars, you, and they, have never been free to be wrong. It was all decided long ago. No need for prophecies. We are all just UTMs with the soul of a marionette

But when you hear the three Global summit prophecies I predicted earlier, consider these three alternatives;

This time is not different, it is not true that AI is calling into question all anthropologies. AI is (only) calling into question a false and reductive Enlightenment prophecy about ‘what it means to be human.’

The perennial systematic and doctrinal anthropology of Christianity understands human being as free-willed, conscious, unified body soul and spirit. It offers credible answers to the urgent questions and cross-pressures society is now wrestling with. It also offers an ethical framework for answering the question ‘what ought computers to be used for and what ought computers not to be used for – even if they appear able to be used for anything and everything?

This Christian philosophical perspective on the twin underlying metaphysical questions of human being and purpose are not being called into question, either at this global summit or by any developments in AI today or the foreseeable future. They can, however, increasingly be called into service to answer those questions – at least for those with ears to hear.