Travelling around recently, considering the impact of the US Civil Rights Movement as part of my sabbatical trip across four States, I’ve been struck by the immediacy of it. It really doesn’t seem very far away, or long ago. Part of that, of course, is its ongoing resonance, but there are also some personal factors. Martin Luther King was just four days younger than my mother, who’s still alive, and I was born in the week leading up to ‘Bloody Sunday’, and the Selma – Montgomery march. Although not strictly true, this feels like a history of my own time.

That sense has, I think, been amplified by some other recent significant dates. Earlier this summer was the sixtieth anniversary of the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech in Washington, the subway in Atlanta is still awash with anniversary posters. Beyond that, of course, just days later, we remembered a similar six decades since the Klu Klux Klan’s bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed; Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley, three 14-year-olds, and one 11-year-old girl. A commemorative service was held in the church, just weeks ago.

History had changed, its arc had indeed bent towards justice. Yet such gestures, profound though they may be, rarely tell the whole story.

Less dramatically, yet still poignantly, 2nd November saw the 40th anniversary of Ronald Reagan signing the bill into law, which created Martin Luther King Day as a national holiday in America, on the 3rd Monday of January each year.

Now very much part of the fabric of national life, the holiday represents, as much as anything, the formal adoption of Dr King as a fully-fledged American hero, part of the great story of the Republic, and the ultimate acceptance of this black man by his country.

Symbols like that matter, such a legacy is significant indeed. It was on Martin Luther King Day 2013, that Barak Obama was inaugurated as President of the United States, for the second time, a black man, who spoke, that day, of a dream fulfilled, as he made his oath of office on King’s bible. History had changed, its arc had indeed bent towards justice. Yet such gestures, profound though they may be, rarely tell the whole story.

Should we be satisfied with the unity that comes from an altogether flatter story, even if it tends towards ‘Disneyfication’, or ought we insist upon messy truth... ?

The holiday wasn’t celebrated until January 1986, Reagan himself wasn’t particularly keen on it, it passed only after something of a battle in Congress where, famously, Senator Jesse Helms led a 16-day filibuster, where he claimed King was a subversive radical, dangerous traitor and communist agitator, And, it wasn’t until 2000 that it was acknowledged in all 50 states.

Such details, if known and remembered, serve to confuse the notion of legacy, to muddy the waters and call into question its real heart. Because the easiest histories are the most straightforward, travelling in a straight line from A to B, from problem to solution, tragedy to victory, despair to hope. They mould into the very fabric of the Nation that the key idea, that the good guys won in the end, like they always do, and the Republic sails inexorably on towards even brighter lights to come.

The question of legacy, when it comes to Dr King, as with many others, is vital for sure, but far more complex than that, and contested too. Should we be satisfied with the unity that comes from an altogether flatter story, even if it tends towards ‘Disneyfication’, or ought we insist upon messy truth, with its inherent conflict and challenge, recalled back then, and still present now?

Martin Luther King was far from a hero at the time of his death, quite the contrary, he was well on his way to becoming a pariah. No longer welcome in the Whitehouse, he had fallen foul of Lyndon Johnson over Vietnam, and his consistent enemies in the FBI now seemed to hold sway there. His relative ‘successes’ with the civil rights act of 1964 and the voting rights act of 1965, genuine and monumental as they were, had only served to demonstrate that a lot of the true causes of segregation, north and south, were less amenable to easy legislative removal, and were actually rooted in economics. As he turned his eye increasingly towards housing in particular and poverty in general, as well as what he called ‘the war question’, he largely lost his platform.

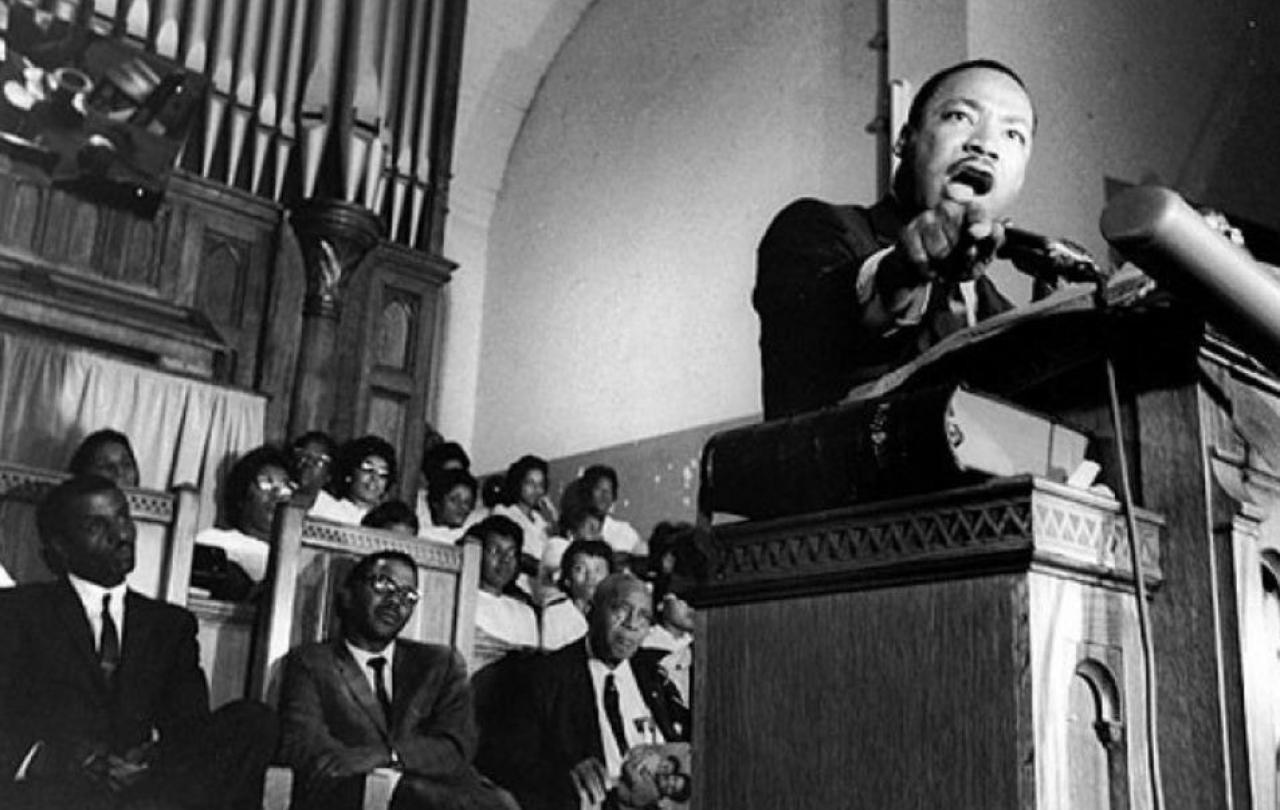

On 4th April 1967, at Riverside Church, New York, he gave what many consider to be his greatest and most eloquent speech ever, but few recall it. Distilling his Christian calling, his civil rights history and sense of present-day necessity, ‘the fierce urgency of now’ as he described it, he began by noting, “surely this is the first time in our nation's history that a significant number of its religious leaders have chosen to move beyond the prophesying of smooth patriotism to the high grounds of a firm dissent …” He went on, after giving a detailed dissection of American history and policy in Asia, to declare that “The war in Vietnam is but a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit.” Before continuing to list out what he called ‘a true revolution of values.’ None of this was designed to win him an appreciative audience in an increasingly materialistic America, and it didn’t. King’s approval ratings, according to polls, were firmly in the negative, and falling. The idea then, that someday soon, the whole nation would come together annually to honour him, was laughable.

Just occasionally though, even in the killing, something is stirred that brings out a legacy more powerful than could ever have been imagined, even more so than national commemorative days.

Of course, death changes things, particularly, premature, violent death. It shocks and inevitably provokes both sympathy, and reassessment. It has us wonder, whether we should’ve listened more carefully, when we had the chance. On this site a few days ago, speaking of the current situation in the Middle East, Graham Tomlin longed for leaders of old who were prepared to break the cycle of violence in the name of peace. My mind turned, inevitably, to Martin Luther King, saying that ‘We will meet your physical force with soul force’. Adding, ‘Do what you will, threaten our children, and we will still love you …we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer, in winning the victory we will not only win our freedom, we will so appeal to your heart and your conscience, that we will win you in the process.”

Such talk rarely, gets you national holidays, named in your honour. It more often gets you killed. Just occasionally though, even in the killing, something is stirred that brings out a legacy more powerful than could ever have been imagined, even more so than national commemorative days.

Legacy speaks of the power of passing on, in the words of Jay Z, turned into a popular pin badge, ‘Rosa sat, so Martin could walk, so Barak could run, so we might fly …’ These cascading consequences of commitment, truthfully sketched out here, and which could’ve gone back further, at least to Maisie Till’s courage in sharing the death of her son, which was said to have inspired Rosa Parks. And, certainly they could also be projected forward. To a multitude of actions, large and small, destined to add to that ongoing legacy of justice. These are, in many instances', the continually ‘rolling waters’ of prophetic imagination that King loved to picture.

In his mind, there is no doubt they find their ultimate source and inspiration in a day set aside to remember, not his though, but Easter Day, when resurrection hope forever shook the world. If, on the 3rd Monday of January each year, some thought might be given to that truth, he could be forgiven a quiet, knowing smile.