Psychotherapists can be really irritating. You may not have noticed how irritating they are, but I have. And that’s saying something. Because I am one - an irritating psychotherapist that is. In nearly two decades of practicing and training people to counsel, coach and generally therapize (I know that’s not really a word, but I can’t help irritating you by using it), I have curated an ever-growing list of the therapeutic practices by which I am most likely to be irritated.

To my mind, the gold medal in the irritating therapist Olympics goes to a winsome and playful hypnotherapist called Stephen Gilligan. Some psychotherapists treat everything that comes out of their clients’ mouths as treasures to be prized, it clearly wasn’t the way Gilligan saw it. In fact, he developed a therapeutic strategy designed to confront any sense that it is possible to define ourselves simply. Every time a client made an ‘I am…’ statement, he would respond with a twinkling eye and a lilting voice, ‘Of course, you are [insert dramatic Pinteresque pause here], except when you’re not.’

Consequently, the pantomime of therapy goes like this. You think you’re a failure? Of course, you are... except when you’re not. You think you’re a coward? Of course, you are... except when you’re not. You think you’re a control freak? Of course, you are... except when you’re not. You think you’re always punctual? Of course, you are... except when you’re not. You think you’re disciplined? Of course, you are... except when you’re not. You think you’re accepting of everyone? Of course, you are... except when you’re not. You think this is all really irritating? Of course, it is... except… You’ve probably got the gist of it by now.

But why would Gilligan, with all his charm and playfulness, risk infuriating his clients like this? Perhaps because he knows something important about human identity that most of us tend to forget. None of us can be summed up in a single sentence, and whenever we try, something grates against us. Any attempt to cram the complex fabric of our lives into the all-too-tiny suitcase of our self-definitions causes us pain. After all that’s what irritation is. It is the gnawing sense that something doesn’t quite fit.

Psychologists note the difference between anger and irritation. When we are angry, we are usually angry at something. Someone or something has blocked our plans. We’re frustrated. It’s not right and we fight against it. There is a sense of indignation and injustice. But with irritation we’re not always sure what’s bothering us, and if we are sure what it is, we’re not sure it should bother us. It’s the young couple whispering behind us in the cinema, the door that only closes with just the right pressure, the person who subtly insults us. Not quite enough to make us leap into action, but just enough to steal our attention. To be irritated is to be slightly annoyed that we are annoyed; to be annoyed while wondering whether we have any reason to be annoyed.

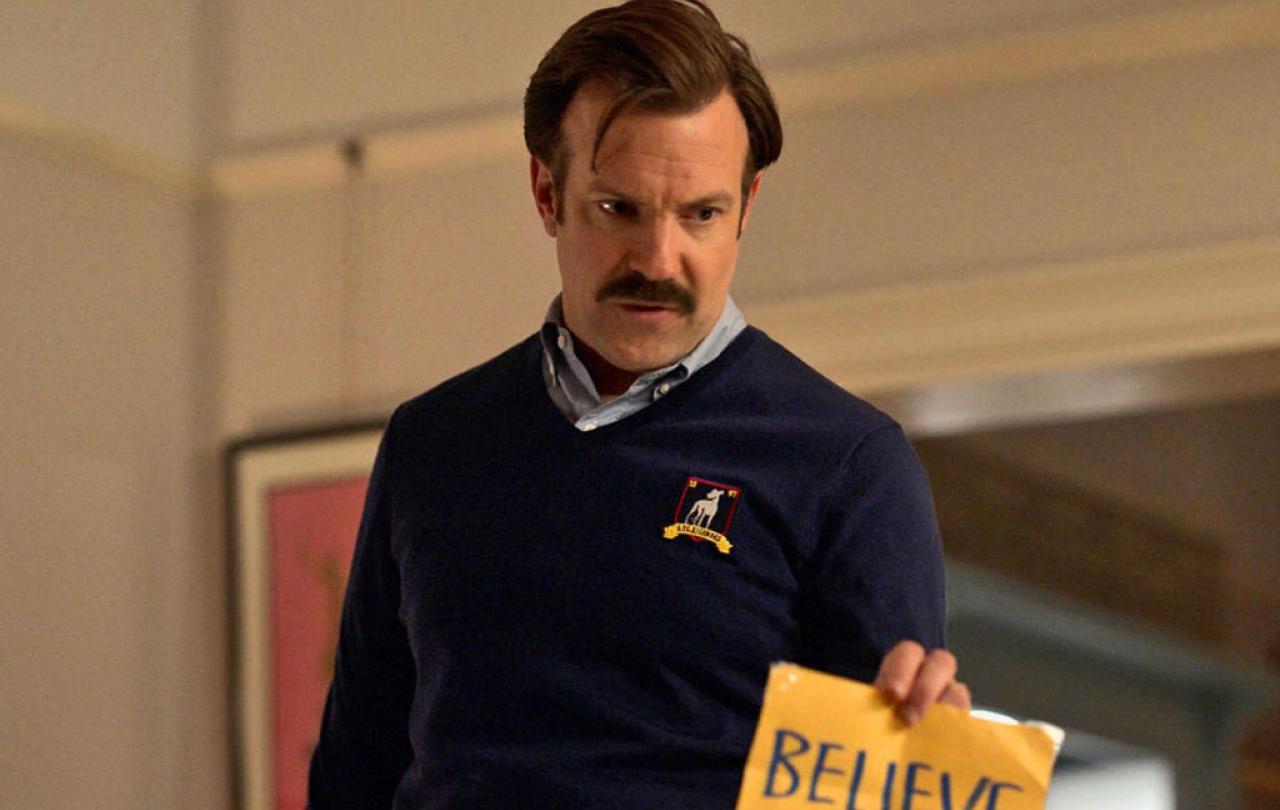

We are whole and perfect just as we are, and no can tell us otherwise. It is the gospel of self-belief, that lingers on the lips of cultural icons from Taylor Swift to Ted Lasso: believe in yourself.

Stephen Gilligan was confronting his clients with the fact that we often wear our identities like this, like ill-fitting clothes that bulge or chafe in the places where the tailoring fails to match the way our lives really are. We can be described in many ways, but we cannot ultimately be contained in, reduced to, or summed up by any single concept. Some part of us always colours outside of the lines. The human equation always leaves a remainder.

The idea that we are ultimately a glorious mystery, even to ourselves, is not a comfortable thing to live with. We would much rather come up with a bold simple label and stick ourselves to it. At least then we’re safe from uncertainty. At least then we’d be something. Most of us to some extent play this game, and the good news is that our culture offers us numerous ways to play it. The bad news is that none of them really work.

Perhaps the most popular way to play the identity game is to believe that we already are everything we need to be. We are whole and perfect just as we are, and no can tell us otherwise. It is the gospel of self-belief, that lingers on the lips of cultural icons from Taylor Swift to Ted Lasso: believe in yourself. You’d think that would be a good thing to believe, but it does run into problems, particularly when the rest of the world fails to hold the same opinion of us.

If we believe ourselves to be wonderful in every respect it comes as a bit of a shock to discover that not all our colleagues, bosses, or friends regard us with the same breathless awe. At this point, many of us modify our view of ourselves to something more realistic. But if we are not prepared to do that, there are only a limited set of options by which to square the circle of knowing ourselves to be magnificent in a world that refuses to agree with us. We can attack the world in rage, we can flee from it in fear, we can hide from it in shame. A surprising number of people respond with paranoia. Which makes sense. If almost everyone you speak to seems intent on undermining your matchless brilliance, you could be forgiven for thinking the world was out to get you. None of these responses are good.

Thankfully, in recent years, therapeutic psychology has issued a corrective to the shortcomings of the self-esteem movement. More nuanced practices of self-acceptance and self-compassion, recognise that it is part of being human to not always be as we would like to be, and we will certainly not always be treated as we think we should be treated. A simple grandiose belief in ourselves is too flimsy to endure the buffeting of real life. Self-belief is not enough.

Accepting acceptance is a radical reorientation of the self because it doesn’t start with us

Some psychologists have argued that the twentieth century should be named ‘The Century of the Self’, the historical period in which Self replaced other larger concerns, such as Country or God, as the ultimate reference point for good human living. The fact that so many of us unthinkingly endorse the need for self-belief, suggests it is a popular option in our current cultural menu of ways to live with ourselves. But it is difficult not conclude that the cultural currents in which we swim are somehow misaligned, or that we suffer from a widespread lack of imagination if the lynchpin of our aspirations doesn’t really deliver. It makes me wonder if we have taken a wrong turn somewhere.

The Christian view of all this is that we as human beings, far from being selves to believe in, are the recipients of a radical kind of acceptance. We are not called upon to generate self-acceptance out of thin air. We have been divinely accepted at the deepest possible level, not because we are special or exceptional, but as a gift to us from a generous God. All we have to do is accept that acceptance. Which is harder than it sounds, because we’d rather believe we did it under our own steam.

Accepting acceptance is a radical reorientation of the self because it doesn’t start with us. It starts with a God who is willing to do whatever it takes to close the distance between us and Him. If God wasn’t like this, if he was vindictive or didn’t care, or if he refused to come anywhere near us until we’d reached the required height of spiritual perfection, there would be absolutely nothing we could do about it. But as it stands, all our attempts to impress God are pretty much useless. There is little point frantically reeling in a god who is already closer to us than we are to ourselves. What’s the point of trying to justify our existence if our existence has already been justified. This is where Christianity begins, but not where it ends.

Divine acceptance does something more. If self-belief asserts that we are what we are, and no-one can tell us any different; then divine acceptance takes us as we are but refuses to leave us there. Something happens to us when we know that we are known and loved right to our bones. We no longer fear being abandoned because of our flaws, and we start to harbour a growing hope that we may be able to overcome them. Our self-awareness improves, we see ourselves more clearly. We learn to live life dynamically, with nothing left prove, but a lot still to learn.