‘Blessed are the peacemakers!’

You can’t really argue with that, can you? It is a truth universally acknowledged, that is deeply embedded in our cultural identity. Like the inherent value of family, fairness and a decent cup of tea, being in favour of peace is of the essence of virtue. After all, who’s going to want to sign up and aspire to an ethic of ‘blessed are the conflict creators’?

But I have begun to wonder whether it’s as clear as all that, and if our intuitive assumptions stand scrutiny.

Of course, we all want ‘peace on earth’, to live peaceful lives in peaceful communities and, at least sometimes, to have some ‘peace and quiet’. Peace is a good thing. We desire it, we embrace it, and we honour those who make it.

But I’m no longer sure we properly grasp what it’s all about. I’ve been on a bit of a journey of late. I’ve come to conclude that it is all a bit murky when you dig beneath the surface.

For a start I have realised that I’m not tuning into the news as much as I used to. OK, to be completely honest I have always been something of a news junkie, and from the Today programme on Radio 4 to various news platforms online I still consume quite a lot. But not as much as I used to.

The relentless stream of violent conflict from Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan and elsewhere to our increasingly polarized political debates, the othering of those we don’t agree with in identity politics and the vitriol of wider culture wars: it gets too much. It seems I’m not alone. A recent report from the Reuters Institute maps a ten-year trend towards disengagement with the news.

I yearn for some breakthroughs on the peacemaking front. In their absence it seems that there is only so much I can take.

Then, my attention was drawn to a piece on the Axios news platform. The headline read, ‘Trump's deep obsession: Winning a Nobel Peace Prize’. That sent me down a rabbit hole.

Now I did already have a half-memory that in his first term President Trump had been a little resentful of the fact that Barak Obama had received the prize while he hadn’t. But it seems it’s more of a thing than that.

Axios reported that he has been ‘obsessed’ with winning the prize for years and that his present administration ‘is aggressively pushing him for a Nobel’. They even suggested that it was the subtext to the Oval Office blowup with Ukrainian President Zelensky.

In fact, President Trump has been nominated for the prize on numerous occasions since 2016, with lawmakers from the US, Scandinavia and Australia putting his name forward.

Awarded 105 times since 1901, while Dr Martin Luther King jr, Nelson Mandela and Mother Teresa might seem to epitomise such an award, there have also been controversies.

The awards given to Mikhail Gorbachev, Yitzhak Rabin, Shimon Peres and Yasser Arafat were particularly controversial. But it was the 1973 award to Henry Kissinger that caused the biggest stir leading two of the five members of the selection committee to resign in protest and howls of derision from the press.

Finally, home alone one evening, I stumbled across Monty Python’s Life of Brian as I surfed the streaming platforms for something to watch. It’s years since I watched it, but it contains one of my favourite scenes of all time.

Jesus is pictured delivering his ‘sermon on the mount’ from atop a small hillock. The camera pans out to the back of the crowd where they’re finding it hard to hear what he’s saying. The conversation goes something like this:

What was that?

I think it was 'Blessed are the cheesemakers.'

Ahh, what's so special about the cheesemakers?

Well, obviously, this is not meant to be taken literally. It refers to any manufacturers of dairy products.

It was chuckling to myself to this familiar pun that provoked a deeper dive. What was Jesus actually wanting to say? What did the crowd hear him say?

A quick look back to the Sermon on the Mount confirmed that ‘the blessings’ that start it off are mainly to those in a seeming position of disadvantage: ‘the poor in spirit … those who mourn … the meek … the merciful … the persecuted’. Why does Jesus include peacemakers who ought to be acclaimed by everyone? They’re the ones doing good stuff with positive benefits. They should be universally acclaimed, why do they need a special blessing?

From the angelic ‘peace on earth’ that heralded Jesus’ birth, to his final gift to his friends, ‘Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you,’ peace is at the heart of what Jesus is about. Receiving peace, giving peace, making peace, ‘peace be with you,’ ‘go in peace,’ peace is littered throughout the gospel stories.

Of course, for Jesus this is shalom or, back in the Aramaic of his mother-tongue shlama. While an everyday greeting the idea infused in the word is far deeper and richer: it is about wholeness and well-being and harmony. Rather than just the absence of noise and conflict, this kind of peace has substance and depth.

Maybe that’s why it has to be ‘made’.

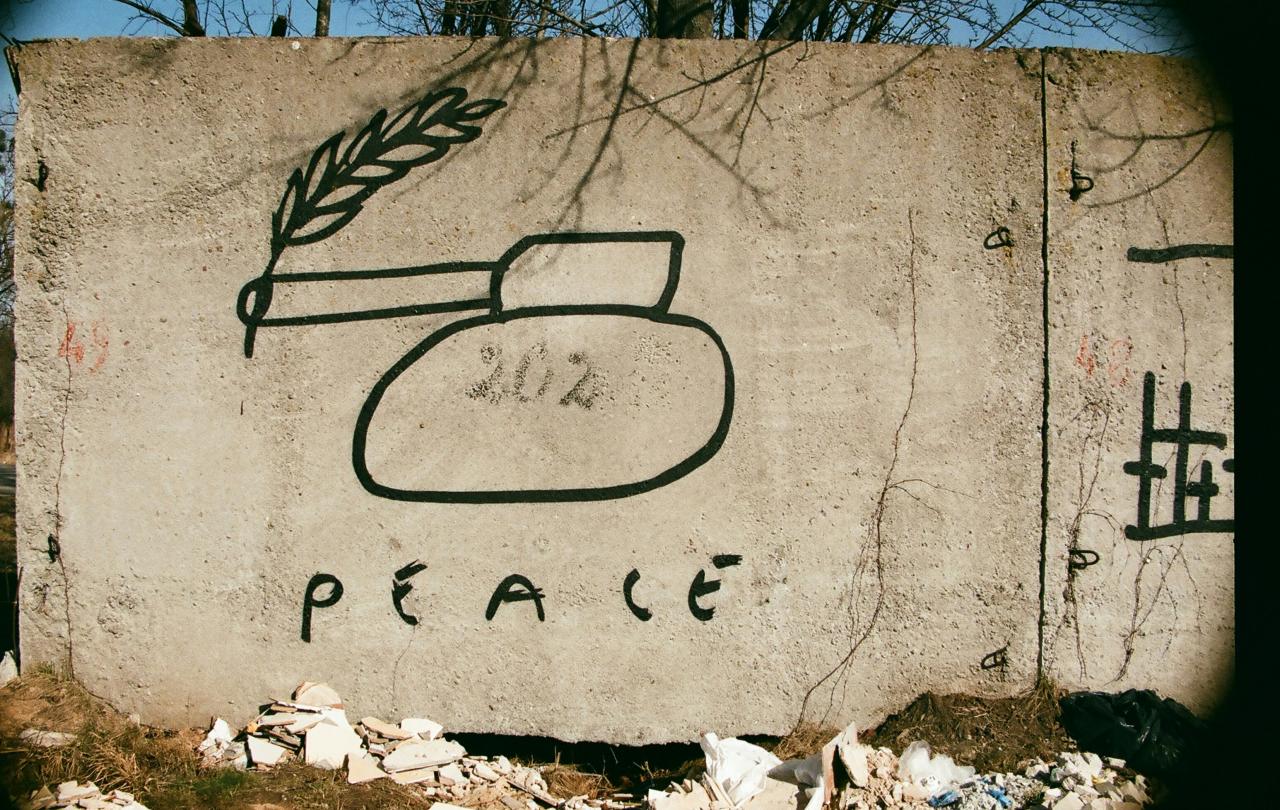

It’s interesting, isn’t it, that Jesus doesn’t say ‘blessed are the peace-lovers’ who merely experience and consume the life of peace. Neither does he major on ‘blessed are the peacekeepers’ who police its boundaries. No, it’s ‘blessed are the peacemakers’, those who’ve got their sleeves rolled up and are actively forging an environment of wholeness, well-being and harmony.

No problem here then. Who’s not in favour of wholeness, well-being and harmony? Well, no-one, until we stumble across what Jesus goes on to say later in this iconic sermon:

"You have heard that it was said, 'Love your neighbour and hate your enemy.' But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.”

According to Jesus, peacemaking is about wholeness, well-being and harmony and its scope extends to, and embraces, even our enemies. And why, because that’s how God does it:

“He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous.”

This is the benchmark that informs the kind of peacemaking that Jesus is talking about.