It’s a World Cup cricket semi-final between India and Australia. Australia are the world champions. They are unbeaten in their last 15 matches, and have won all their group matches impressively. They are overwhelming favourites. India have lost three of their group matches and only just managed to qualify for the semi-finals.

The match is being played in Mumbai. The ground is packed and millions are watching on television. Australia win the toss and bat first. They make 338 runs in their 50 overs, an outstanding score. India are facing the highest run chase in World Cup history to win the match.

India’s innings gets underway and a wicket goes down in the second over.

Out walks Jemimah Rodrigues, 25 years young, nervous, in front of a full crowd of 45,000, in the city where she was born and grew up. Earlier in the competition she had been dropped from the team. Just over 3 hours later she is 127 not out, off of just 134 balls, and she has steered India to one of the greatest wins in Women’s World Cup history, and her innings has been described as one of the greatest World Cup innings of all time.

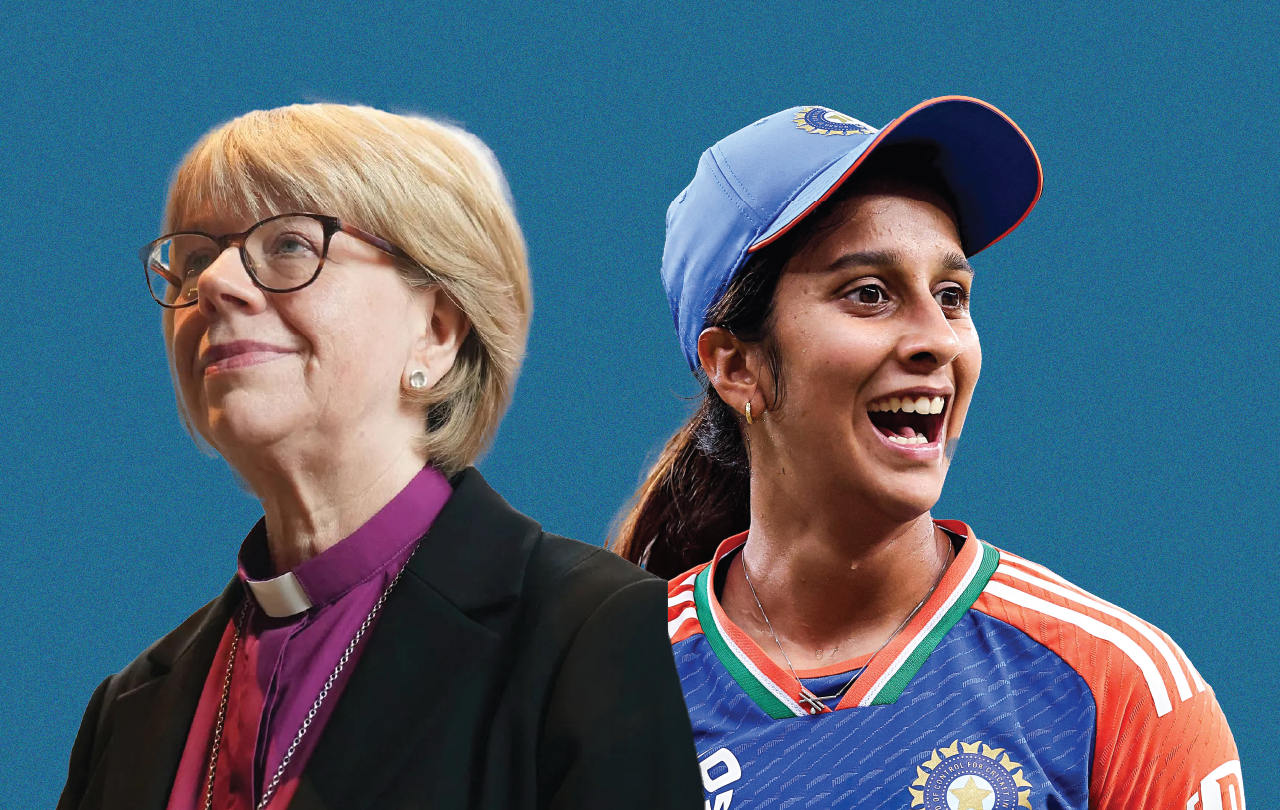

What does she have in common with Archbishop-elect Sarah Mullally? They are both Christians, sisters in the worldwide family of God’s Church, and when they were both young children neither knew that there was any possibility of their being where they are now.

Jemimah Rodrigues was born in September 2000 and as a child didn’t know women’s cricket existed. She played with her two older brothers, and hockey looked a more likely avenue for her sporting talents. When she went to play cricket, encouraged by her parents, she was the only girl among 500 boys. Playing in a women’s cricket World Cup final watched by a sell-out crowd? Not possible, surely.

Sarah Mullally was born in March 1962. A woman as Archbishop of Canterbury? It was 1994 before the first women became priests, and 2015 when the first woman was a Bishop.

Now Jemimah Rodrigues has inspired a nation with her sensational innings that led to the defeat of the previously all-conquering Australian women’s team, and India went on to win the final against a resilient South Africa side in front of another packed crowd in Mumbai. It was the first time India’s women’s cricket team had won the World Cup. The most famous Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar posted on his social media of the team: “They have inspired countless young girls across the country to pick up a bat and ball, take the field and believe that they too can lift that trophy one day”. The Indian men’s cricket team’s head coach Gautam Gambhir posted: “You have not just created history, you’ve created a legacy that will inspire generations of girls.” Sarah Mullally becoming Archbishop of Canterbury will similarly inspire generations of young girls in their hopes and aspirations.

But there is even more to Jemimah’s inspiring legacy than encouraging girls to use their sporting gifts and helping to change the culture so that can happen. She has also been very open and honest about her struggles, disappointments, anxieties and about her very genuine Christian faith. In interviews she has spoken about how as a very young girl she was in a swimming pool when her young cousin tragically drowned and how that brought on a deep anxiety in her. She couldn’t face being in a classroom, she needed her mother there. She has continued to be open about nerves, crying, mental health, anxiety and to express gratitude for her family, her friends, her teammates (most of whom are Hindus) and for her Christian faith for the support and help they have given her. The first words in her post match interview after her match-winning 127 were a thank you to Jesus and the next were to thank her family. Another mindset she mentions is her concern to bat not for herself, but for the team. “I wanted to see a win for India, not something about myself.” She has also referenced a conversation with the above-mentioned legend of the Indian game Sachin Tendulkar who asked her about playing international cricket: “Are you nervous?” “Yes” was Jemimah’s immediate, honest reply, to which Tendulkar said “You are nervous because that means you care about doing well. So just go out and do your best”.

Jemimah Rodrigues has shown an honesty, a concern for others, for the team not herself, and an openness. “I will be vulnerable because I know if someone is watching they might be going through the same thing. That’s my whole purpose in saying it. I was going through a lot of anxiety at the start of the World Cup tournament.” And yes she does get trolls on her social media, but she will continue to be herself as God wants her to be. “When I am weak, then I am strong” writes Saint Paul to the Christians in Corinth giving him a hard time, and “I will keep on doing what I am doing”.

Here’s to more great innings from Jemimah Rodrigues (though she knows God’s love for her does not depend on her cricketing performances), and to more opportunities for girls as well as boys to use and enjoy their sporting gifts. And may Archbishop Sarah, as well as having in common with Jemimah a Christian faith and a story of opening up opportunities, share that aim of honesty and openness and may she know great victories along the way, not for herself but for the worldwide team of God’s Church.