Pilgrimage, according to Pete Grieg’s definition at least, is simply ‘a journey with God, in search of God’. In other words, it’s not going from somewhere God isn’t, to where he is, but does recognise the real power of place, that the presence of God, experienced in a specific location, is significant, and worthy of seeking out.

I’ve been reluctant to call this sabbatical trip of mine, to the sites of a variety of events significant in the American journey towards civil rights in the 1950s and 60s, a pilgrimage. It sounds overly grand and to give too strong an emphasis to the geography, rather than either the history, or the biography, of Martin Luther King himself, the inspiration of the whole journey.

Yet, as I’ve been travelling; by plane, train, car and foot, I’ve been powerfully moved, as I’ve stood in places that have carried the weight of real pain, and extreme significance. There is genuine emotion attached to being somewhere where something happened, barely a generation ago, it leaves a legacy hanging in the air which is somehow palpable. That’s true regardless, but it’s often helped, although sometimes hindered, by some sort of maker. Something to let you know that this is where it was. Beyond the purely informational, memorialising has, or can, play a potent part in demanding that attention be continually paid to the past’s relevance to the here and now.

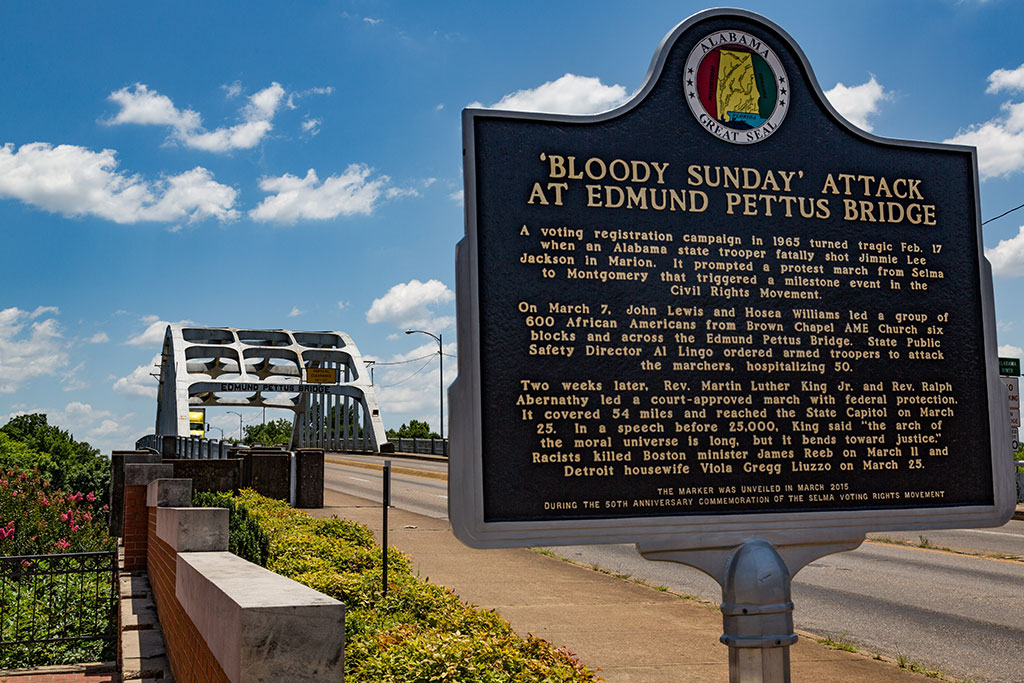

Selma, Alabama

A historic marker at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Tony Webster, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Those responsible for keeping this particular story alive, across the United States have, it seems to me, done an exceptional job in providing markers and memorials that both focus and amplify the meaning of the events they commemorate. Allow me to take you with me, briefly, to some of the places where I have stood, that you might sense something of what I have felt.

The USA, of course, has some experience of memorialising significant, yet relatively recent events. Coming from the UK, where I’m used to public monuments largely celebrating victory, glorifying generals and affirming a pretty static sense of solid certainty, it’s refreshing to witness commemorations that provoke as many questions as they provide answers, that promote reflection and challenge, as well as inform.

Washington DC is, of course, a city of memorials. Some of the most well known are, strictly speaking, outside of the remit of my trip, but it seems wasteful not to visit nonetheless.

The monuments to Lincoln, Jefferson and Washington himself are famously huge, grand and imposing, yet, to my mind at least, the most moving Presidential memorials are those to Roosevelt and Mason, the forgotten founder. Relatively small, humble even, thoughtful, the small wheelchair bound figure of Roosevelt, almost lost within his own expansive legacy, generously populated with the images of others, especially the poor, they put aside prestige for the sake of the personal.

When it comes to war, there’s a welcome note of ambiguity, whether you are scarred by the gash in the landscape that is the Vietnam memorial or haunted by the staring eyes of the Unnamed soldiers of the Korean war, catching you accusingly with their glance, there’s no place for mere glorification here.

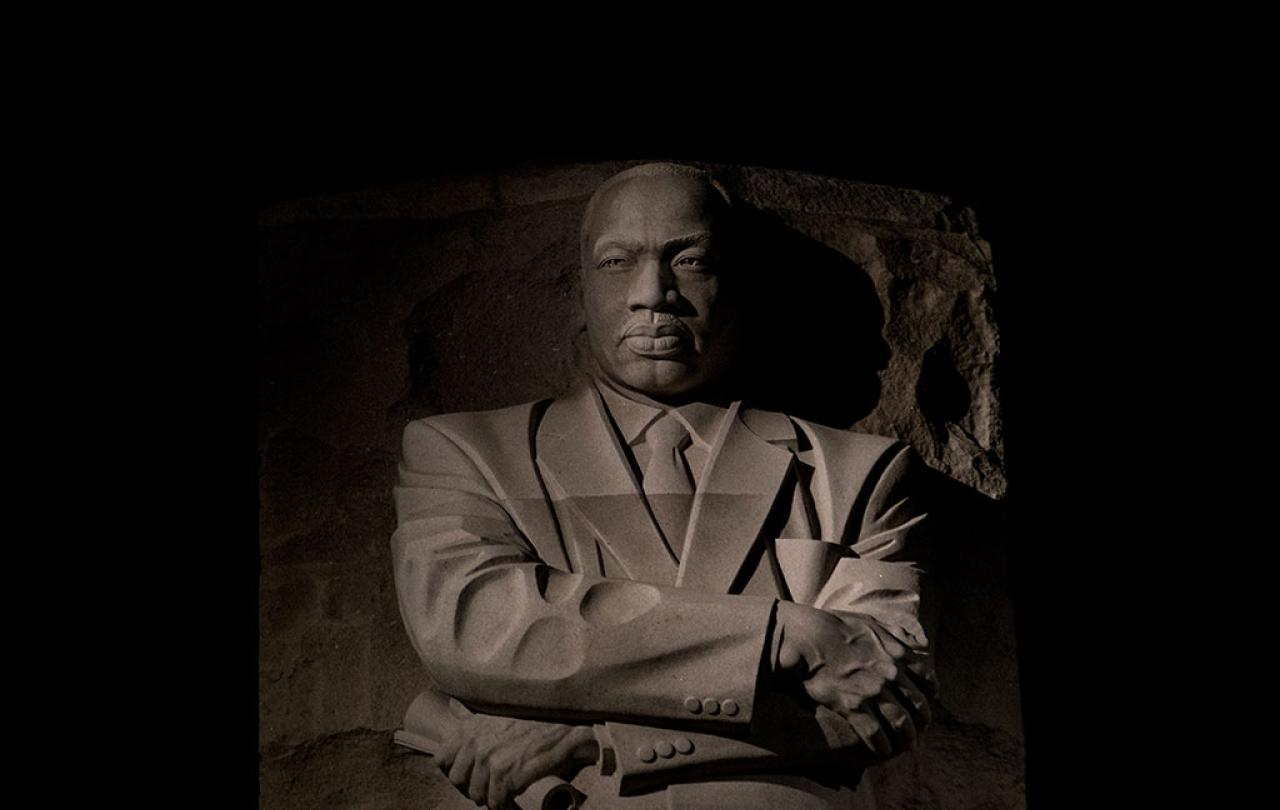

Of course, the one non president remembered on the National Mall, takes me to the heart of my journey. Martin Luther King stands, tall and majestic, emerging, literally, out of the rock face behind him. ‘Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.’ Powerful, in every respect, but I would have to go elsewhere to find his humanity.

Like to his birth home, in Atanta, beside the very dining table where he was told by his father that the reason the inseparable friend of his pre-school years dropped him as soon as school began, was because of the colour of his skin, and that it would happen over and over again. Or, later, at the kitchen table of the parsonage of his first church in Montgomery, where, having cleared up the wreckage from his bombed porch, he wondered, in the middle of the night, if the burden he was carrying was too great to carry, and yet, right there, experienced an encounter with God that fuelled his every succeeding day.

Maybe to Boston, the most recent, abstract yet tender monument to the ‘Embrace’ between him and his wife, a marriage far from perfect, yet powerfully enabling.

Or perhaps standing in his very footsteps, marked for posterity, at the Lincoln memorial for the March on Washington, the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, perhaps the most searingly evocative place of all that I visited, or behind his own beloved pulpit from Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Montgomery. In each and every place, recalling all the different stories, you get a feel for the man, his pain, and yet his faith.

Then there were the larger museums, interpretive centres and institutes, designed to show the bigger picture still.

Like the enormously impressive National African American Museum of Art and History (NAAMAH), part of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, where, I joined, in quick succession, a weeping line of black American visitors, filling past Emmett Till’s open casket, then, the same crowd, cheering the recorded promise of a Dream.

The Civil Rights Museum of Birmingham, charged with overseeing the 16th Street Baptist Church, and the place, just outside the ladies’ rest room, where a bomb exploded. killing 4 young girls, just as a service was about to begin, as well as the pretty little park opposite, with its startling sculptures of snarling police dogs and water cannons.

There was the Legacy Museum, from Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, in Montgomery, where you’re immediately overwhelmed by storm force waves crashing all around the walls and ceiling, enveloping you in the immersive experience of the transatlantic slave trade. Before peering into a tiny cell and seeing a holographic figure come to life before you, a slave waiting their auction, telling you their story. Then, much more up to date, being ushered into a prison visiting room, picking up the telephone to hear the convict’s take on contemporary racial injustice.

Birmingham, Alabama

Freedom Walk, Kelly Ingram Park.

Carol M. Highsmith, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Or, just down the road, in the Rosa Parks Museum, standing at a bus stop, watching a small, tired lady being hauled off to be arrested for falling to give up her seat, before you move on, another half mile or so, to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and feel the weight of the multitude of great steel blocks, 800 of them, each representing a county in America, bearing the names of the victims of summary lynching.

Finally, there’s the gentle water flowing over Maya Lin’s follow up piece to her Vietnam memorial, the civil rights memorial, also in Montgomery. All of these places, and others; bitter with anger, drenched in tears, seared with hope. Remembered, celebrated, with all their ongoing awkwardness as benchmarks in history and faith.

In an age when the role of statues and memorials is much debated, when history, it’s said, should know its place, and yet be allowed to stand and speak its truth … these places, images, powerful exhibits and presentations, demand that the whole, painful truth shout out its reality, often in the name of the victims and the vanquished. In doing so, they bear good witness to the events that they’re designed to speak of. They inform, but, much more than that, they move and they challenge, they create new and ongoing stories so that history is not only recalled but re-enabled in a needy present, and offered up in hope.