Foreboding. That’s how my friend described the time between now and the election in America. It’s everywhere, and nowhere. It’s felt, it’s lived, it’s immediate. And it’s true, there is little reason to carry ourselves as though this election will be anything other than consequential—immediately so—for at-risk communities across the United States, from hurricane survivors to Haitian-Americans.

We would do well to pay attention to this. And for me, as an American citizen, I plan on casting my vote against Trump, for what I wager to be a better path towards provisional freedom. But there’s a part of me that remains attentive to the stakes and the perils that lie beneath the immediate.

As you survey the landscape of the American experiment, you will find it marred not just by scars of racial hatred and violence, but the shadows of things forgotten and repressed. Looking over it long enough will reveal the chasm between America’s living memory and its history. It’s here, surveying that great landscape, the gap emerges between what “We the People” choose to remember and what we’ve deigned to forget. And this memory—as much as the polls and the data predict—will influence what is to transpire these next few months.

As we bear witness to the events unfolding before us, we would do well to remember how “We the People” have never truly resolved our Civil War. Our memory of the war is both hallowed and haunted.

If onlookers and participants alike want to understand—really and truly—the crucible of this American election you have to descend to the depths of American memory, into its distortions and attempted preservations. You have to understand not just the Civil War itself, but its ongoing aftermath, from a period called Reconstruction to the century later Civil Rights struggle, and on to today. Recently I heard historian Jemar Tisby share an anecdote of something uttered by a Gettysburg battlefield tour guide, “The north won the war,” he said, “but the south won the memory.”

Who has time for a history lesson? I would submit the stakes are too great, and the need too earnest, to ignore.

Memory is a fickle thing. But it is also a moral thing. Memory gathers the resources from which individuals become a “we.” That is the point where everything begins to change, observes John Steinbeck. That move from “I” to “We,” he called it. Memory can create a people. From it, a “we” can draw strength, clarity, and courage for the present, it can also reap the whirlwind.

Theologian Stanley Hauerwas captured the stakes when he observed, “memory is a moral exercise.” And in a moment where the American social fabric seems to be rending at the seams (not at all an unprecedented event), I think part of staying the course involves turning again to the moral power of memory. To remember what we’ve forgotten, to surface what has been buried.

But in the middle of an election cycle endlessly bombarding Americans with hate, disinformation, and propaganda, the turn to memory might seem little more than idealism. Who has time for a history lesson? I would submit the stakes are too great, and the need too earnest, to ignore. The problem is: the American memory is distorted and divided.

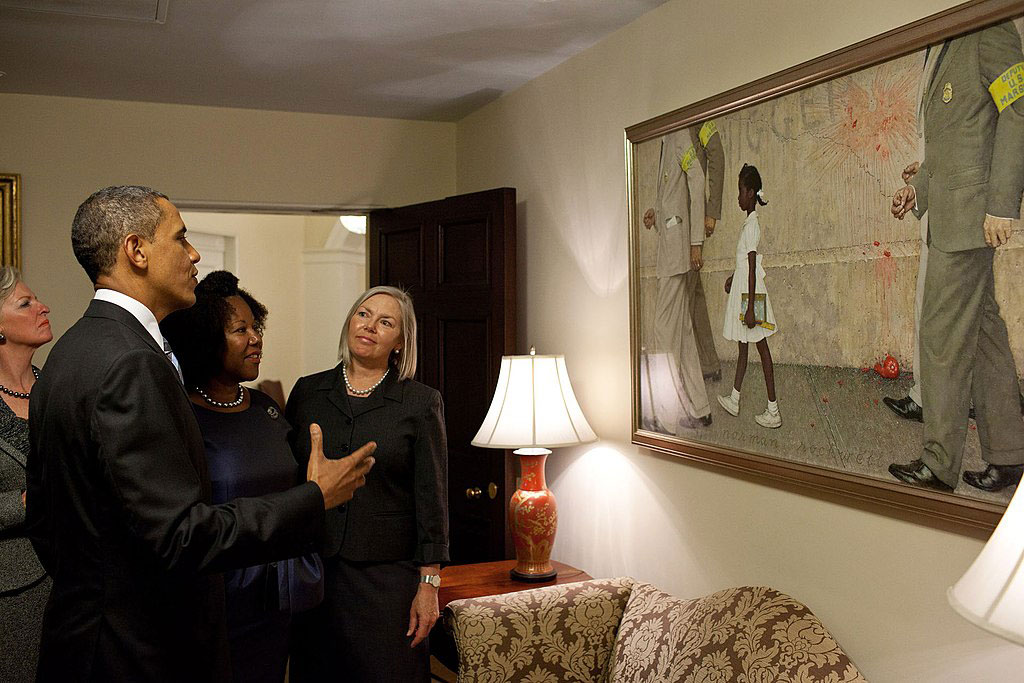

Ruby Bridges visits Barack Obama at the White House to view 'The Problem We Have To Live With' on its walls, 2011.

In 1960, a six-year-old girl by the name of Ruby Bridges became the first African American to attend William Franz Elementary School in New Orleans. She walked into the school that day surrounded by armed guards, assigned to protect her from public fury in the wake of a federal court order enforcing integration across New Orleans Public Schools.

Ruby became an icon of the Civil Rights struggle of the Sixties. She was canonized by artist Norman Rockwell in a piece aptly titled, “The Problem We All Live With.” Between that painting and hundreds of photographs that captured her bold yet innocent stride up those school steps with books in hand, Ruby Bridges was impressed into American memory.

Consigned to these mists of memory, Ruby Bridges appears as perpetually six years old to many white Americans. But one fact pierces the mists of memory: Ruby Bridges has an Instagram. Though her memory in white America reduces her to an image frozen in time, she is a woman alive today in her sixties with an incredible ongoing career in advocacy and activism. The cries of “woke!” that emerge in every conversation about justice and equity in America cannot silence the reality of time: the Civil Rights struggle is not so distant as white Americans often insist it was. What we remember is tragically the result of what we’ve tried to forget.

But whenever the church settles to serve as a chaplain of empire, it soon confuses the privilege and luxury it secures with its own freedom.

We tend to think of history as objective, as a set of facts. And this obscures how our own memory of history can be distorted and warped. Consider this past month that former US President Jimmy Carter turned 100 while in hospice care. His birthday made mainstream news. An impressive lifespan to go with an incredible legacy as a husband, father, and public servant. But the American memory is strange. Strange because Carter, the oldest living US President, is still with us. Making it all the more startling to remember that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King was born 5 years after President Carter. That, if not for an assassin's bullet at a Memphis hotel balcony in 1968, Dr. King could have been celebrating his 96th birthday this coming January. Memory can be distorted, warped, and pressed into service of propaganda.

Too often, the white church in America has made itself fit for service as a chaplain of empire. Willingly producing, baptizing, or consuming memories which obscure the truth that brings about reconciliation. In so many words, we have in America today a more reactionary and partisan element of the church. One that cannot take the moral responsibility of memory seriously because it finds itself too invested in its role of reifying and deifying America. And whenever the church settles to serve as a chaplain of empire, it soon confuses the privilege and luxury it secures with its own freedom. Because many white churches confuse this power with freedom, the memory of America is captive to its own ends. It is not free. It does not know the freedom which liberates the church to the moral task of memory.

I think here of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s claim that the church can never take immediate or “direct” political action as church because, as the community of God’s people it “does not know the necessary course of history.” The church does not possess special access to the ideas of the future, nor does it consign the world to fate. What the church is, it is as witness. It testifies in the bread, the wine, the water of the liberating presence of God. But when the church acts apart from this vocation it risks becoming what Ernst Kasemann called the “anti-church” which replaces the cross with power.

I find this a broadly accurate depiction of what the white American church presently offers to the American public. It is not the beloved community and conscience of the nation to which Martin Luther King Jr. spoke, rather it is a chaplain of empire. And in this role, the church finds itself both a producer and consumer of a distorted memory, filled with a mixture of sentiment, propaganda, and raw fact. A story of America in service of a particular vision of America which never existed.

Is this not too political for the church? Mustn’t we keep religion and politics separate? All theology is political. That is, all human talk about God involves consequences—for good or ill—concerning fellow human beings. James Cone puts it more directly: “Any talk about God that fails to make God's liberation of the oppressed its starting point is not Christian.” The difference then is not whether the church is political, but rather whether its talk about God is indeed talk which remembers in a living way the God of Jesus Christ, and whether or not it opens itself up to the critical examination of its own god talk. And this is where we find a good deal of the white American church today.

Even the mention of the “white church” in America should stir up the paradoxes and contradictions which persist in the field of American memory. But perhaps we too easily confuse “history” with “memory.” Memory is living, fluid, and potent. I like how Robert Jenson puts it, “so long as a people is alive, there will be an exchange between how it remembers its history at any given time and its needs, concerns, and goings-on in the present. There is thus usually a difference between a people’s own living memory…and the accounts constructed by historians…” Jenson was talking about the Old Testament. Here, we reflect a bit on the American experiment.

I remember in 2020, as a pastor, I sat in a prayer night at the church where I served on staff. But there was not much praying. Instead, we were shown a video selected by our senior pastor. The video was a tour of Washington D.C. highlighting all the Christian imagery and inscriptions scattered across the American capital. I’ll never forget the words that came from my pastor: “The next time,” he said, “anyone tells you America isn’t a Christian nation, you tell them about what you learned here tonight.” And that was it. The video never mentioned many of the buildings were built by the hands of people enslaved in an institution justified by a most bankrupt faith.

I’ve come to understand that every church in America, even with the Christian story on its lips, tells a story about America, too. And the memory of that story carries with it theological consequences. After all, there can be no quicker way to discredit human words about the God of Jesus Christ than to attach those words to a false memory of America masquerading as dogma.

The statute of General Longstreet, Gettysburg battlefield.

Stranger still was realizing the church I served was constructed on a piece of land in Virginia’s Spotsylvania County lined with historical markers. One identifies the land as the camp site of Confederate General James Longstreet during the Fredericksburg Campaign of the Civil War. Tellingly, Longstreet’s own life and legacy gives witness to the enigma of memory and also the possibility of change that arises from the wedding of truth and reconciliation.

Longstreet was long known as General Robert E. Lee’s right-hand man. He devoted himself to the Confederate cause in defense of slavery. And stood by Lee till the end of the war, joining him at Appomattox, Virginia, where he was reunited with his foe and friend, Union General Ulysses S. Grant. Instead of imposing harsh penalties on the Confederates, Grant proved reconciliatory in ways that Longstreet never forgot, according to his biographer, Elizabeth Varnon.

In fact, Longstreet became an ardent supporter of Reconstruction policies and Civil Rights, including the vote, for formerly enslaved people. His transformation made him an enigmatic figure that attracted the bitter hatred of fellow former Confederates seeking a scapegoat for the South’s defeat. They found their sacrifice in Longstreet.

After the war, Longstreet settled in New Orleans for business. In 1872, there was a disputed election between pro-Reconstruction Republican governor and the Democrats. Longstreet answered the call from the Republican governor to lead a “mixed” regiment of African Americans and white Americans against a renegade paramilitary force comprised mainly of disgruntled Confederate veterans. These paramilitary groups opposed the African American vote and Reconstruction policies in general to the point of violence.

In a historical episode that echoes January 6, 2021, Longstreet, a former Confederate General, led this Reconstruction regiment against white paramilitary insurrectionists seeking to subvert the election and install their own governor. The clash became known as the Battle of Canal Street. But its original name was given by the nearly successful Confederate paramilitary: “The Battle of Liberty Place.” This was the name affixed to a monument erected in 1891, which stood in New Orleans until it was removed under cover of darkness for fear of political violence in 2017.

The stark transformation of Longstreet’s life and career does not make the man a saint. He clung to racist ideologies until his death. To emphasize his support of Reconstruction is not to canonize him as much as it is to highlight the enigma of American memory. That, in the wake of the Civil War, the conflict over Reconstruction proved so destructive that eventually whites from the North and the South opted to reconcile at the expense of Civil Rights. In the contested Presidential Election of 1877, Republicans accepted the Presidency in exchanged for the Democrat’s demand for an end to Reconstruction and a withdrawal of Federal troops. The dealings of 1877 made Jim Crow America possible, and forestalled gains of the Civil Rights movement for nearly another century. And the question remains open: will America ever deliver on its promises? This is the appeal made by MLK and others.

And our failure to remember as Americans is, surely, part of the task of the church in America. For a witness to the Christian story surely involves a freedom to speak truths of our common life and history which make for reconciliation. For me, as the election nears, I’m thinking of the enigma of Longstreet and the distortion of American memory.

For in the very church that claimed America was a “Christian nation” merely by virtue of slogans fixed atop our public buildings, there was along with it a willed ignorance to matters of race in our own community. I experienced enforced silence on just how far a pastor might talk about race before being “too political” or “divisive.” I found there is a tragic irony of failed memory in gathering to worship on land once occupied by Longstreet’s camp, the man who supported Civil Rights and resisted an insurrection. After I left, I learned the church’s parking lot was made available for busses attending the event that metastasized into the January 6 insurrection. And just this past month, thousands of evangelicals descended once again into Washington DC, praying and declaring Trump’s victory against Harris. Here too, the whitewashing of January 6 has its own consequences.

Amid the raging fury of an American election cycle, memory can help provide perspective, so long as we are willing to incriminate ourselves with the sins of forgetfulness and short-sightedness. There are events forever etched into our collective memory, to be sure. We have slogans for them. Like “Remember Pearl Harbor” and “Never Forget” for 9/11. But even here, amidst cries to remember, our memory persists in a state of perpeutal division and distortion. The slogans we create to remember the tragic dead too easily become transformed into a license for our unflinching commitment to the myth of redemptive violence.

Again and again we see, memory carries moral power. And without truth in our memory, there can be no reconciliation. But I remain hopeful precisely because I do not worship fate. The confession which binds Christian community speaks of the God who reconciles. This reconciliation is received as a grace by the truth of Jesus Christ.

Whether or not “We The People” renew our capacity to speak the necessary truths, to live in that light, and so prove reconciliation to be a lived reality not mere sentiment, depends in no small part on the willingness of Christian community in America to take up the fuller and deeper ministry of reconciliation bound up in our confession. Such a ministry cannot be one of external compulsion, of endorsing authoritarian politics and programs in the name of another crusade. Rather, it is one that begins and ends with the question of whether the church will be the church. Whether or not America continues as America does not rest on the church. And freed from this strange, alien imposition, the church may find itself all the more fit to help America remember and so tell the truth and reconcile together.

So long as we Americans allows ourselves the freedom to recognize the inherent relationship between truth and reconciliation, perhaps we can carve out a higher vantage point from which the stakes and perils of this election become a bit clearer and stir in us a bit more courage to persevere in what Lincoln spelled out over a century ago, a new birth of freedom and government of, by, and for the people…all the people. And may the church stand to testify that this temporal freedom is only a fleeting harbringer of a freedom which comes to all humanity through the scandal of a cross and empty grave.