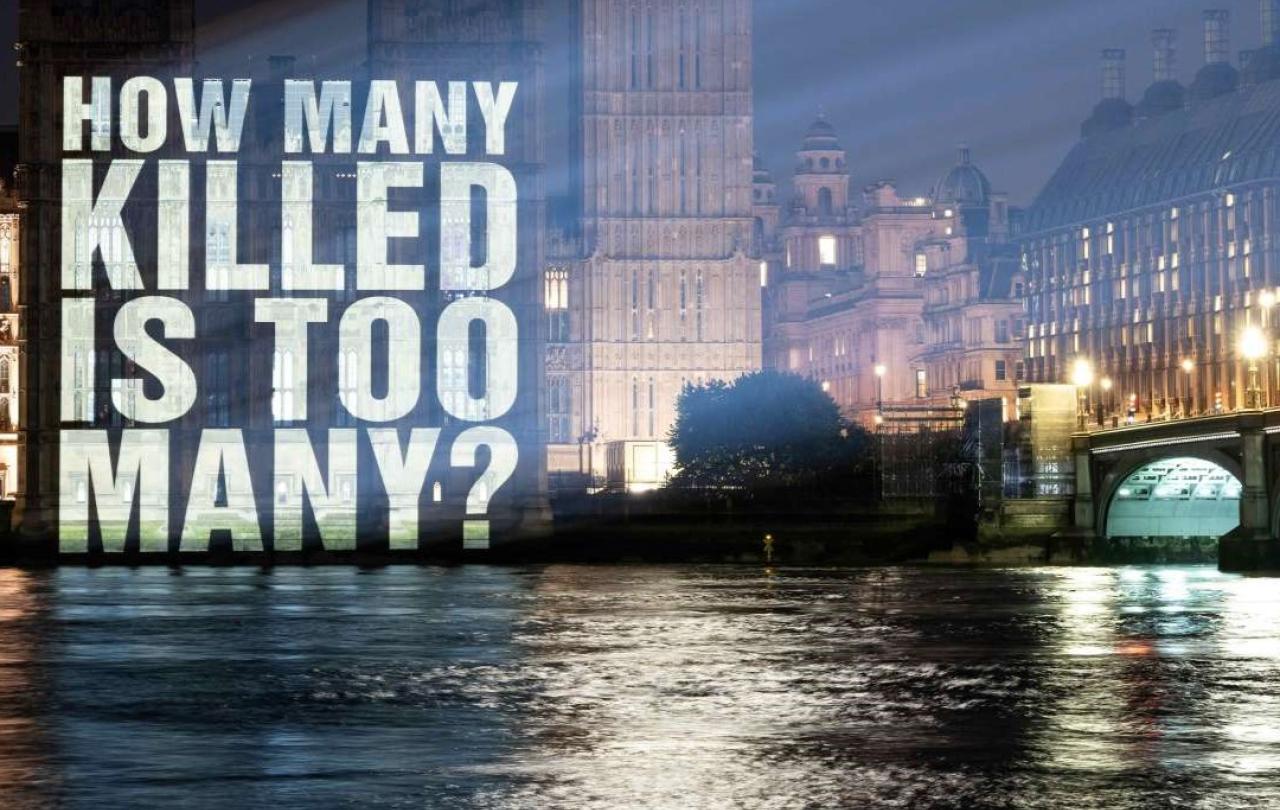

Whichever side you take in the Israel-Gaza conflict, the stories can't help bring a sense of desperation. Images of starving children, the fate of Jewish hostages still held in darkness - either way, this remains a place of unimaginable suffering. And meanwhile, the bombs keep dropping, people die, and Hamas retains its hold.

Among Israel’s friends, voices have been murmuring a radical solution to the problem of Gaza. Donald Trump’s plan was to raze the territory to the ground, shift 50 million tonnes of debris and displace its people to neighbouring countries to build the ‘Riviera of the Middle East’ in what had until now, been Gaza. The plan might have been met with some amusement when it was aired, but it gave permission for many within Israel to think similar thoughts.

Bezalel Smotrich, the Israeli finance minister, recently claimed that after the Israeli operation, “Gaza will be entirely destroyed” and its Palestinian population will “leave in great numbers to third countries.” Many within Israel seem to think the stubborn, Hamas-ridden enemy living next door needs to be eradicated. To a population weary of decades of conflict, fearing that there will never be peace while Hamas remains in Gaza, and aware of how difficult it is to winkle out the Islamic terrorist group while the Palestinian population remains there, you can understand the attraction of this radical solution.

However, the Israelis might have good reason to be cautious. And that is not a counsel from their opponents - but from their own history.

In the early 130s AD, the boot was on the other foot. It was the mighty Gentile Roman Empire that ruled over the same patch of land, which they were soon to call Palestina. Jews were a minority, but they still harked back to their long roots in the land, the days of Joshua and King David, and even more recently to the Jewish Hasmonean kingdom 200 years before - the last time before the modern state of Israel that Jews were in control of the land.

The emperor at the time, Hadrian, passed through Jerusalem in 130 AD, along with his entourage and his lover, the young slave boy Antinous. He started to paganise the city, erecting statues of gods and emperors, even of his young favourite, all of them offensive to Jewish sensibilities. The smouldering resentment soon erupted with a revolt led by a fierce and determined Jewish fighter, Bar Kokhba. This was the second Jewish uprising after the earlier one in the 60s that had led to the destruction of the great Jewish Temple in Jerusalem by Titus, under the reign of the emperor Vespasian in 70 AD. For the Romans, one revolt might just be tolerated, two was too much.

Hadrian came to the same conclusion as Bezalel Smotrich – a rebellious territory had to be erased from the map, although this time, it was Jerusalem that was to be eliminated, not Gaza. Its Jewish population was to be scattered, its name deleted, and memories of past glories buried for good.

And so, in 135 AD, the bulldozers moved in. Jerusalem was effectively flattened, and a Roman city built on its ruins. Aelia Capitolina was its new name, a smaller city, yet decadently built around the worship of Greek and Roman gods, with splendid gates, pagan Temples, a classic Roman Forum, expansive columned streets – not quite the Riviera of the middle east, but maybe the Las Vegas. ‘Jerusalem’ was scrubbed from the map.

At the centre of the sacred Jewish Temple Mount, Hadrian erected a statue of himself. He deliberately planted a statue of Aphrodite over the very spot where the early Christians insisted that the death and resurrection of Jesus had taken place – where the Church of the Holy Sepulchre stands today. Circumcision was outlawed, many Jews were killed, and those remaining were banned from the city, dispersed anywhere where they could find shelter. In fact, the map of the Old City of Jerusalem today is still marked by this design, with the two main Hadrianic streets diverging south from the Damascus Gate, with archaeological remains of the Roman city still visible for visitors.

Yet of course it didn’t work. No-one calls it Aelia today. People's attachment to land goes deep. The Jews could not forget their roots in this patch of the earth's surface. As Simon Sebag Montefiore put it: “the Jewish longing for Jerusalem never faltered”, praying three times a day throughout the following centuries: “may it be your will that the temple be rebuilt soon in our days.”

Palestinian attachment to land is similarly strong. Nearly 80 years after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, families still cling on to the keys to homes that were taken from them during that traumatic period. Like the Jewish yearning for Jerusalem, they too, like people across the world, have a deep attachment to ancestral lands, which go back to the ‘Arabs’ mentioned in the book of Acts, to whom St Peter preached in the early days of the Christian church.

Executive decisions by distant rulers such as the emperor Hadrian or President Trump might seem like neat solutions to intractable problems. But they seldom work in the long term.

The famous biblical injunction ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth’ was meant not as an encouragement to violence but the exact reverse. It was mean to set a limit to the development of blood feuds, which could, out of anger and trauma, so easily lead to disproportionate reaction and never-ending vendettas. When St Paul wrote “Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord’”, he was recalling an ancient piece of Jewish wisdom that set limits on human capacity to sort out intractable problems by violence. He knew a better way: “Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.”

Luke Bretherton, Regius Professor of Moral Theology at Oxford and a Seen & Unseen writer, argues that there are really only four ways you can deal with neighbours who prove difficult: you can try to control them, cause them to flee, you can kill them, or you can do politics – in other words, try to negotiate some form of common life, as ultimately happened in Northern Ireland, South Africa, and so many places of long-standing conflict.

Politics, the business of learning how to live together across difference, is messy, complicated and hard work. Especially so when there are deep hurts from the past. Yet, as the failure of Hadrian’s radical solution shows, there is no real alternative in the long term.

Join us

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief