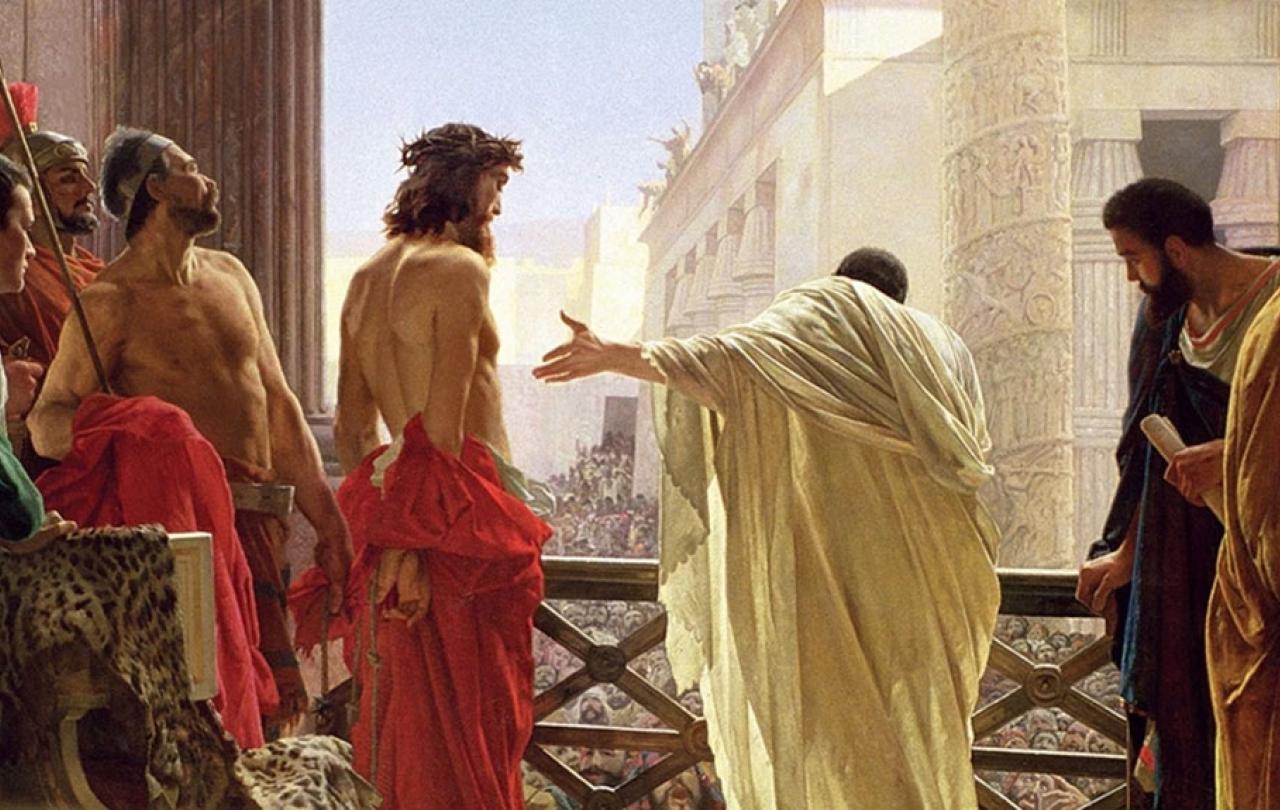

I’ve had a lot of Pontius Pilate in my life lately. And this week he’s set to play arguably the second-biggest role in human history, as the Passion of the Christ reaches its climax on Good Friday.

The reason I’ve been spending a lot of time with Pilate is that I’ve done a podcast about him for Things Unseen, which sounds like a sister operation for this platform, but isn’t. Its title was Pontius Pilate: A man like us and addressed the question “Was the man who sent Jesus to the cross evil or merely weak?”

I’m accustomed to Pilate being a paradigm for flawed human leadership – vain, indecisive, distracted, cowardly. A former archdeacon of London, the Ven. Lyle Dennen, had a very good stock sermon entitled “Pontius Pilate’s Brother”, in which he recalled that his elder sibling had played Pilate in a school play.

Consequently, the headmaster had made a habit of greeting little Lyle in the corridor with the words: “Ah, if it isn’t Pontius Pilate’s brother.” It was an engaging way to develop the thought that we’re all Pilate’s brothers and sisters, collectively executing the Christ on a daily basis.

My fellow podcast panellist, the novelist and musician Chibundu Onuzo, was having none of this “Pilate inside us” stuff, making the case for his particular circumstantial weakness. It’s a good listen. But it’s set me thinking, since we recorded it a fortnight ago, a whole lot more about the local Roman procurator, the man who has history’s worst morning at the office.

I’ve come to consider that there is a third way, a via media, between this being a verbatim transcript and a metaphor for his judgment by worldly authorities.

The veracity of Pilate’s gospel role is hotly disputed. He’s undoubtedly a real historical figure, as is Jesus of Nazareth, and his jurisdiction presided over the crucifixion of the latter. Beyond that, the interpretation of his scriptural role varies.

Perhaps it was written back, particularly in John’s gospel, as a means of exculpating the repressive Romans of Jesus’s death and putting the blame firmly on the Jews (with very terrible historical consequences).

If that is even partly so, we’re invited to view Pilate’s interrogation of Jesus in his palace allegorically; especially around Pilate’s rhetorical question of Jesus, “What is truth?”, when the answer is literally standing right in front of him and from which he doesn’t even bother to await an answer.

So if this gospel section contains the kind of truth that the Nazarene’s parables held, what is it meant to tell us? I’ve come to consider that there is a third way, a via media, between this being a verbatim transcript and a metaphor for his judgment by worldly authorities.

Pilate, as he faces the mob bent of insurrection and baying for blood outside the praetorium, is an agent of worldly chaos too, a lord of misrule

Before I left for a holiday in the Balkans early this month, I decided on a book to take with me. Should I re-read Ann Wroe’s excellent Pilate: The biography of an invented man, in preparation for the podcast? No, I thought, there’s plenty of time for that. So I took a novel I’ve been meaning to read for decades, Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita.

Alarmingly, it turns out that Bulgakov’s novel has a recurrent deconstructive sub-plot of the fate of Pilate running throughout it. This was the sort of coincidence of which we’re taught to be suspicious at theological college. So I paid attention.

The book’s main narrative is a satire of Stalin’s post-revolutionary Russia. Satan, in the character of Woland, visits Moscow to see how things are going. Death and destruction ensue, as Woland and his weird retinue cause havoc. Yet, along the way (spoiler alert), he reconciles a crazed and failed author (the Master) to the love of his life (Margarita), which is not a bad thing to do.

A lot of it is in the rather annoying style of magic realism. But annoyance is a point. The work of a devil in human affairs is annoying, but it doesn’t have the last word, just as Pilate doesn’t.

What I took from this novel was the darkness of chaos before the divine order that is brought in the act of creation, from which humanity constantly falls back into chaos.

Woland isn’t really evil (he’s quite kind to Margarita and may even be in love with her), he’s just the agent of chaos, like Pilate. A lord of misrule, if you will.

We have many such agents of chaos in the world, from US and European politics, to Russia (again) and Ukraine, from Israel and Gaza to the famine of Sudan and the global technological interference of China.

Pilate, as he faces the mob bent of insurrection and baying for blood outside the praetorium, is an agent of worldly chaos too, a lord of misrule. But as Bulgakov’s novel tells us, he can be redeemed.

The difference between him and us is that we have the benefit of hindsight. When we ask despairingly, like him, on all the Good Fridays that afflict the world, “What is truth?”, we may not (also like him) recognise it.

But, unlike him, we have the chance finally to recognise that truth, as it stands right in front of us on Easter morning.