Sometime between 95 and 110 AD, a Christian called John the Evangelist (it is said) wrote about ‘the spirit of the Antichrist, which you have heard is coming, and even now is now already in the world.’

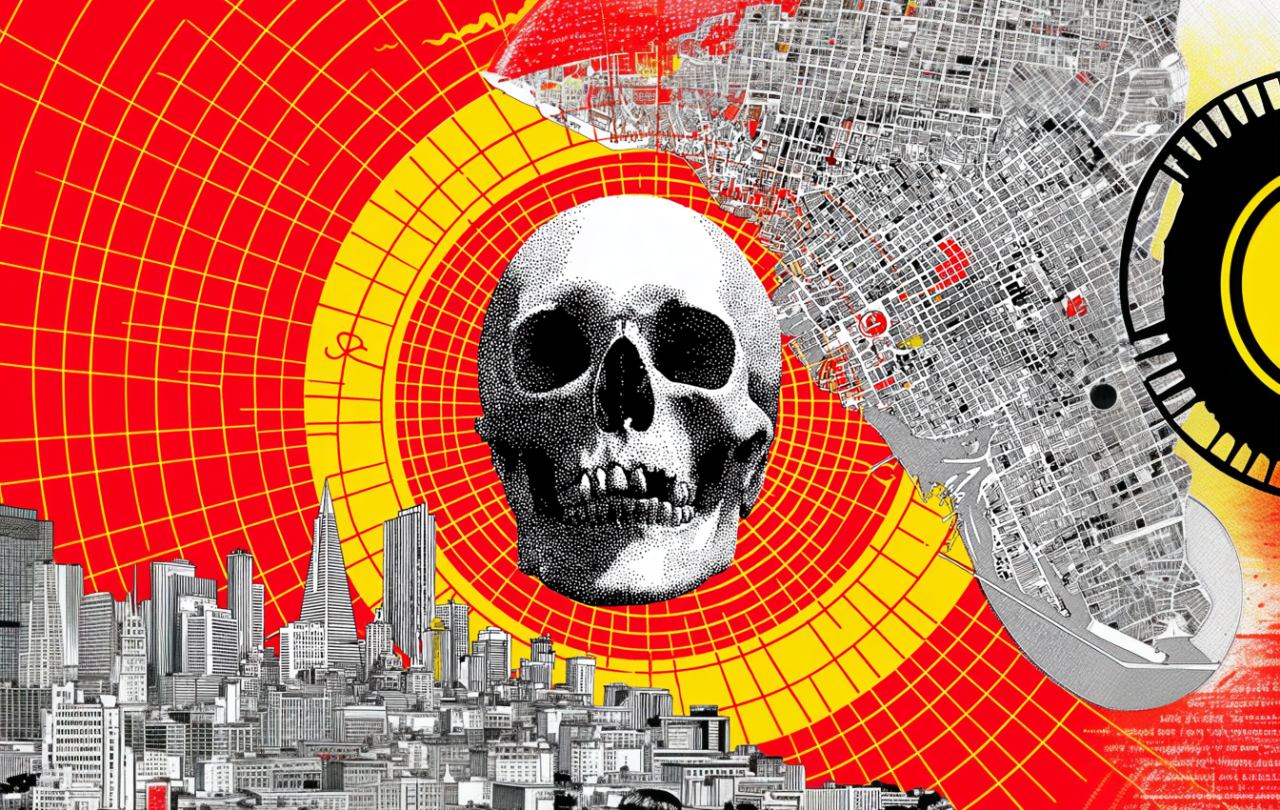

Fast forward two thousand years, and the Antichrist is back on the agenda, this time via Peter Thiel, the co-founder of PayPal and Palantir (a data analytics company) and the first external investor in Facebook, who is currently offering his thoughts on the “politics of the Antichrist” in a four-part lecture series in San Francisco.

Thiel previously said, in an interview in 2024, that he thinks that if the ‘Antichrist were to come to power, it would be by talking about Armageddon all the time.’ By Armageddon, he means the destruction of the world arising, for instance, from nuclear war, bioweapons, climate change, or AI. And in that interview, Thiel referenced an instructional documentary film from 1946: One World or None. Its thesis is that the answer to atomic warfare is to have the nations of the world unite. According to Thiel, such a global government would be the most insidious danger of them all. ‘The slogan of the Antichrist,’ he said, is ‘peace and safety’, which ‘resonates’ in ‘a world where the stakes are so absolute, where the alternative to peace and safety is Armageddon’. So, the promise of perfect peace is a false one: it would lead only to a one-world totalitarian government.

We have been here before. On 13 January 1814, at one of thousands of services of national thanksgiving to celebrate the Peninsular Army’s entry into France, which heralded the end of the Napoleonic Wars, The Venerable Joseph Holden Pott, the Archdeacon, ascended the pulpit in the St Martin-in-the Fields Church on Trafalgar Square in central London. There had, he said, never been a ‘fitter moment’ to encourage ‘patriot zeal’ ‘on sound and righteous principles’, which he expounded for his flock. Jesus Christ was ‘a true patriot’. First, he loved the place of his birth and the people around him; then, he demonstrated love for the whole world. The ‘spirit of true Patriotism regards the good of other Countries as connected always with its own.’ However, one’s home country always come first.

Throughout the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon, who rose to power on the wave of revolutionary unrest in France, was cast by the ruling elite in Britain as the Antichrist. Protestant Britain was depicted as the new Israel, which would deliver Europe from all its woes. With the risk of political Armageddon in their own country, the establishment reasserted the importance of religion to the nation state.

The politics of the Antichrist will always tend to have traction, but the risk is that the response to the belief that the Beast is rising out of the sea, to use the image deployed in the Christian Bible, will be just as destructive: a religious revival that is all about reactionary politics or remembrance of things past.

Thiel’s take on history is that it its linear, angled toward the End Times. His thought is cyclical, collapsing in on itself, in that it is a tired trope that has been used before. For instance, it has been used during the Napoleonic Wars, and it is not guaranteed by a strong faith that can move mountains, which is arguably what the world needs more than anything else.

Saint John meant, by the ‘spirit of the Antichrist’, ‘every spirit that does not acknowledge’ Jesus Christ as Lord. And soon after, the early Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria, who sold Christianity in a competitive marketplace, wrote about the ‘sects both of barbarian and Hellenic philosophy’ that unlike Christ ‘each vaunts as the whole truth the portion which has fallen to its lot’.

The risk with Thiel is that he is simply validating unchecked ‘tech’ taking over the world. It is also sectarian that Thiel’s thoughts, for all their seemingly counter-cultural boldness, are often expressed in the shadows. His remarks in his current lecture series in San Francisco, for example, will go unrecorded. They are speculative in their nature.

By contrast, those writers who lived through the first half of the twentieth century, which Thiel sees as a turning point in the politics of the Antichrist, flaunted their wares in public, with incisive clarity. They spoke of the way in which the spirit of Christ transcends time and all other ideology, like Clement of Alexandria in the first century.

One such writer was C. S. Lewis, who wrote an article ‘On Living in Atomic Age’ (first published in 1948), in which he exhorted us not to exaggerate ‘the novelty of our situation’. We were always going to die, irrespective of the politics of the world around us, and as ever our mission is to better ourselves by turning to Christ. We should not assume that we alone can save the world. But Peter Thiel sounds he like does.

So, we still have much to learn from the Christians from the early church. Saint Paul wrote to Christians in Thessalonica warning them not to be deceived by the Antichrist, who ‘sets himself up in God’s temple, proclaiming himself to be God.’ And anyone encountering Peter Thiel’s (or indeed any one’s persons) political ideas would do well to remember that.

The PayPal founder’s obsession with the Beast is nothing new.

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief