In a depressing sign that all creativity and originality is truly fading from the world, we are offered another India Jones film - Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. We are offered a third farewell to a beloved character that robs him of all the wit, charm, charisma, and esteem he ever had. We are served a platter of mildly uninspiring nostalgia-bait cameos, CGI set-pieces, a plot thinner than a communion-wafer, and a finale that seems to be the sleep-deprived fever dream of an over-worked and over-caffeinated script writer meeting a deadline.

It opens in style, and on comfortable ground. We’re back on the Nazis. GREAT! If there’s one thing Indiana Jones can do, it is punch Nazis. A hooded figure is dragged into a soon to be bombed castle that is being looted by retreating Nazi soldiers. The hood is removed, and we see… young Harrison Ford? Not quite, but not bad. As far as de-aging technology goes it could be worse…but then the voice. There is no way to get around the fact that 80-year-old Ford sounds markedly different to 45-year-old Ford, and that just rips you straight out of the film.

The rest of the opening set-piece never recovers, and is so saturated with CGI, that it fails to engage or excite. This goes for much of the film (with the exception of quite a fun car chase through the streets of Tangier) – scenes set leagues under the sea, or miles high in the sky, are so weightless and empty as to be boring. Despite being far greater in scope, they don’t even come close to matching the rollercoaster tension of the mine-car chase in Temple, or heart-stopping wonder of the jump from the horse to the tank in Crusade, or the juvenile joy of the aborted sword-fight/shootout in Raiders. Anyway, Indy stops the Nazi train, seemingly dispatches Mads Mikkelsen’s Nazi scientist, and manages to steal the Antikythera mechanism of Archimedes. Toby Jones adds some light relief as his partner in adventure and is on screen far too little.

Pheobe Waller-Bridge... does snark and sarcasm and raised eyebrows better than most, but that isn’t a good foil for Indy. Indy is the snarky one.

Cut to 25 years later and Indy is a shadow of his former self: an alcoholic, exhausted, uninspired shell of a college professor, counting down the days to death now that he and Marion have separated. It is impossible to say who this film is for. It can’t be for fans of the original, who must be horrified to see the great Indy reduced to this. It can’t be for newcomers who have no way of understanding why this man is significant, and in what way this degeneration is meaningful. So, who is it for? People who hate the character and want him to be taken down a peg or two? This feeling seems to inspire the cameos also – don’t put Sallah and Marion in an Indiana Jones film for a combined screen time of five minutes or less!

Anyway, the plot develops and there isn’t much of it, which is fine; an Indiana Jones film is ultimately a collection of set-piece fetch quests strung together, and that can be glorious…when done right. Indy must team up with his estranged goddaughter (who’s father was Toby Jones) and a bargain-basement Short Round (what I would have done to see Ke Huy Quan properly reprise the role) to find the other half of the Antikythera mechanism before Mads Mikkelsen and his group of Nazis who are hiding-in-plain-sight. Why? Time travel. Obviously.

The performances are fine. Harrison Ford does grouch better than most, and seems to actually be putting effort in. Pheobe Waller-Bridge is…Pheobe Waller-Bridge. Being Pheobe Waller-Bridge is fine…is great! I think Fleabag is one of the best pieces of television we’ve had in the last decade (especially season two). She does snark and sarcasm and raised eyebrows better than most, but that isn’t a good foil for Indy. Indy is the snarky one, Indy is the mocking one. It isn’t Waller-Bridge’s fault, it is what she was given to work with, but it is annoying and upsetting. Mads Mikkelsen is brilliant – the one shining light in the gloom – because he is always brilliant and should be in all films.

To say one genuinely, properly positive thing: the score is lovely. If this is John Williams’ final outing, then what a way to go!

Do we have to break Indy down? Do we have to end with him so broken and pathetic that he would rather give up than fight, and who must be punched by his goddaughter for the film to be resolved?

Clearly, I’m a little upset and am ranting somewhat…but this is important. Indiana Jones is an iconic character, especially to young boys. I don’t want to get into the discourse on men refusing to relinquish control of certain protagonist archetypes, because that isn’t what I argue for. Adventurers, spies, soldier, boxers, etc…all characters that have had excellent female lead portrayals and certainly should have more, if that is what creators and audiences want. But…can we have this not at the expense of a beloved character? Do we have to break Indy down? Do we have to end with him so broken and pathetic that he would rather give up than fight, and who must be punched by his goddaughter for the film to be resolved?

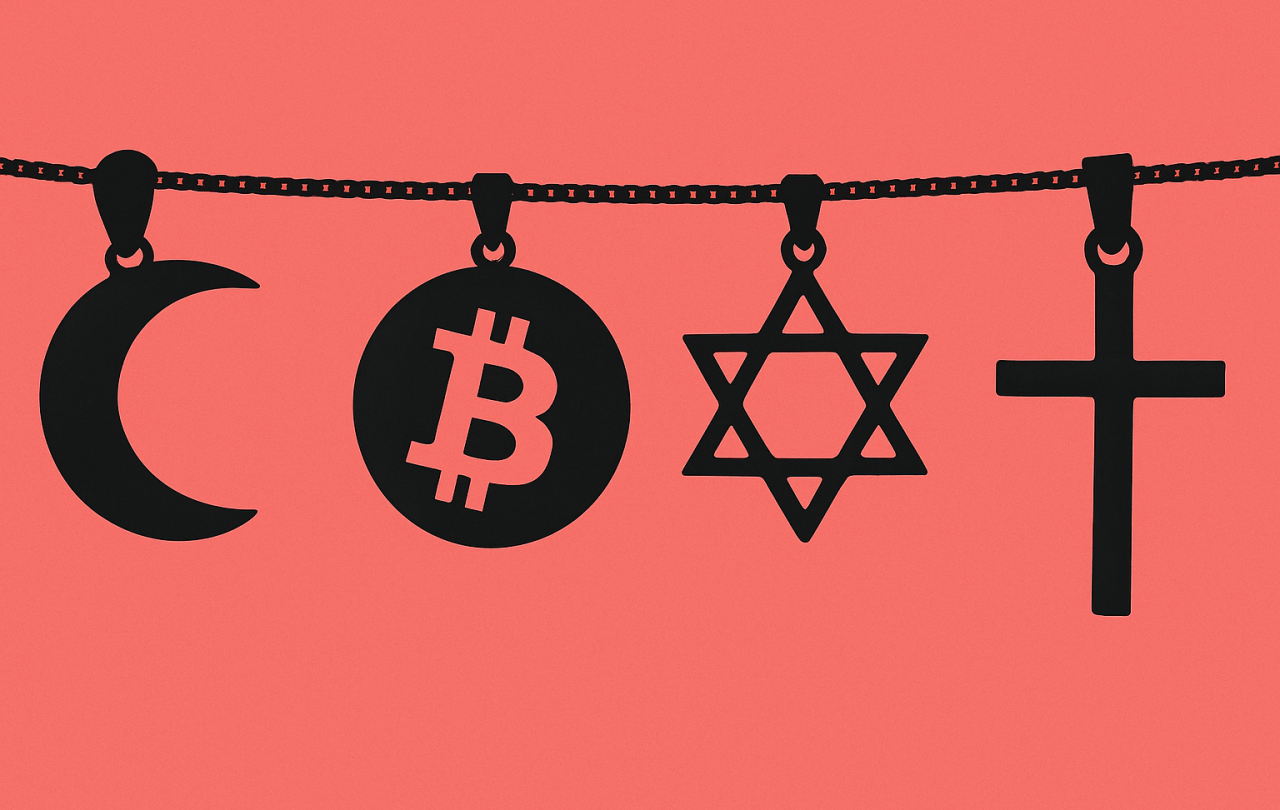

Okay, let's try to take this out of a context that can lead to toxic online discourse. Let’s park the question of whether we’ve gone too far in breaking down good role models for young men (we have, and we ought to stop). Let’s just look at role-models in general. In the Church such role models are called saints. They point us to the practices and prayers that can bring us to holiness, that can bring us closer to God. We remember them for their great and mighty deeds. For some it is victory in great spiritual struggle – like St Anthony punching demons in the face. For others it is achievement in great theological study – like a St Thomas Aquinas or a Richard Hooker. Some are titans of charity – St Francis – who inspire others to set up schools and hospitals – a St John Bosco or the nuns in Call the Midwife.

We don’t slavishly worship their every waking thought or act. We know they were human; they were fallible, they were sinners! Some saints are saintly because they give us an insight into their own complexity and nuance and fallenness – St Augustine’s Confessions is a text that everyone should read every year. But we don’t linger on their faults, and foibles, and indiscretions. That is a recipe for despondency. We know the saints weren’t perfect, but we look to their great and godly example for inspiration.

It was C.S. Lewis who complained, almost a century ago, of the inability of post-war fiction to paint in black and white. I agree, and Dial is an example of this.

I’ve complained in reviews before about the fact that we seem to be unable to have proper villains. This film doesn’t fall into that trap – Mads Mikkelsen’s Jürgen Voller is just evil, a proper Nazi, the most ‘Nazi’ Nazi there is, more Nazi than Hitler! – but it doesn’t want to give us a decent hero. I think it was C. S. Lewis who complained, almost a century ago, of the inability of post-war fiction to paint in black and white. I agree, and Dial is an example of this. Sometimes we need to be reminded of good and bad, holiness and evil, and that we ought to turn to one and away from the other.

Dial of Destiny is a bit of a nothing film that robs Indy of a decent goodbye – he had a great one riding into the sunset with his father and with Sallah, and an okay one when he married Marion – but it is significant in continuing the trend we see of robbing heroes of their heroism, as other films rob villains of their villainy. It would be nice to see a return to great adventure epics showing us a bit of black-and-white. It is good for soul – it gives us something to aspire to, and something to flee from…it gives us an example to follow.

2/5 stars – just watch the original trilogy.