In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, there lived an anonymous mystic who we’ve since come to know as Julian of Norwich. After coming chillingly close to death at the age of thirty, she spent the subsequent decades of her life in a small side room of St Julian of Norwich church (the inspiration behind her pseudonym), speaking to people only through windows and writing masterfully about her supernatural visions of God.

Her anonymity, modesty, and creativity meant that she was free to write about God without the pressure of being theologically or doctrinally ‘correct’. She wasn’t too interested in making her writing academically bulletproof, nor was she too bothered with institutional rightness.

Rather, she experienced, and she wrote. She pondered and she wrote. She suffered and she wrote. She rejoiced and she wrote.

She was utterly captivated by God, and that meant that she was free.

I think that Nick Cave is free, too.

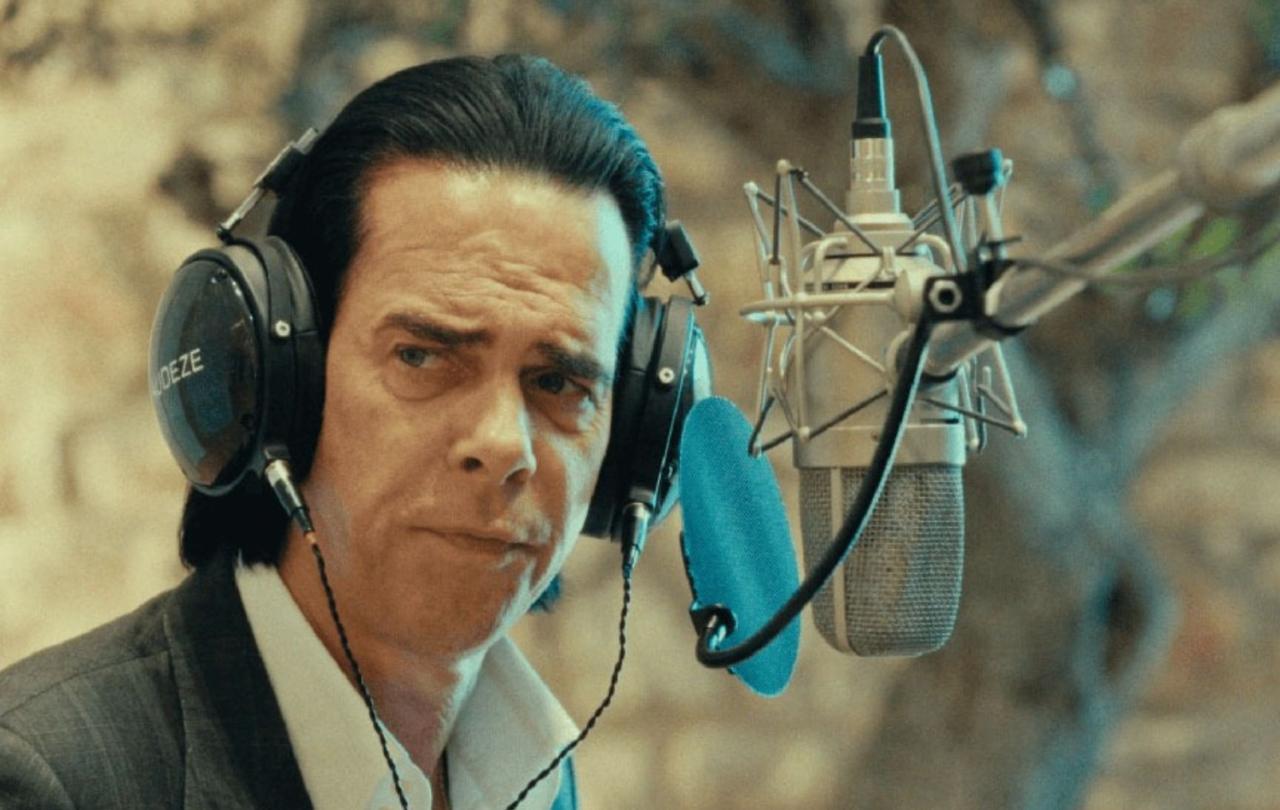

His latest album reminds me of Julian of Norwich’s work; baffling, subversive, mystical, rooted in a truth that can’t be proven. A truth he wouldn’t be interested in proving, anyway. It, too, swerves ‘rightness’. It, too, refuses to dilute the oddness of faith. It, too, is irresistibly intense. I pressed ‘play’ at around 8:03am this morning, assuming that this album would be the soundtrack to my mundane morning. But two songs in, I found myself sitting on my kitchen floor with my coffee, a notebook, and the album turned up to a volume that would have justifiably annoyed the neighbours.

This is not a casual album. Any true Nick Cave fan would scold me for ever expecting it to be.

The album is a ten-track-long ode to a Wild God who has met Nick in the darkest of places. Places, I’m sure, he never wanted to go. Places, I’m sure, he will never fully leave. Such a wild God is a challenge to a culture that has enthroned comfort. We’re too easily spooked. But Cave, through a combination of circumstance and intentionality, appears to have entirely shunned comfort. And so, he’s in prime position to introduce us to a God who will confound us.

Julian of Norwich’s book and Nick Cave’s album are centuries apart – yet, somehow, it feels as though they have been made from the same materials: profound discomfort and raw wonder.

Suddenly, you’re reminded that you’re eavesdropping on a man who has lost his son, conversing with a God who lost his too.

This is Cave’s eighteenth album with the Bad Seeds. Together, they have created a soundscape to get lost in, a changeable climate controlled by their instruments: you get caught up in a cyclone during the title track, the cymbals crash like waves on the shore in ‘The Final Rescue Attempt’, you can hear the gentle droplets of rain fall in ‘Frogs’, the strings somehow sound like a sunset in ‘As The Waters Cover The Sea’.

It’s music that baffles your senses.

And then there are the stories that the songs are telling.

The album opens mid-way through a bar, its first song – ‘Song of the Lake’ - sounds as if it was playing before you hit play. In 2015, Nick and his wife Susie lost their teenage son. In 2022, Nick lost another son. The last two albums offered up by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – Skeleton Tree and Ghosteen – they have an address, and the address is grief. They’re laced with palpable agony. And so, beginning this album mid-way through a bar, it’s as if Nick is telling us that we’re picking up a conversation where we left off in 2019. This album wouldn’t exist if the previous two didn’t exist.

He uses the opening song to remind us of the tragic circumstances in which he lost his teenage son, Arthur, by referencing the nursery rhyme character, Humpty Dumpty – who, of course, ‘had a great fall’. Nick quotes, ‘… and all the king's horses and all the…’ before cutting himself off with ‘… oh never mind. Never mind.’

What’s the meaning of this recurring ‘never mind’? Is it agony or acceptance? Maybe it’s both. Maybe it’s neither. Maybe Nick, as usual, doesn’t want to be too knowable.

Some of his thoughts feel finished and firm, others feel unexplored and new – like we’re hearing them at the same time that Nick is. On occasion it feels as though he’s teaching us something, on other occasions, he’s the one asking the questions. It’s about him, and then it’s not about him. It is intensely personal and then it’s cosmically minded. It’s sturdy, then it’s fragile. It’s from the point of view of a deity, then it’s from the perspective of a frog in his pocket.

It is pretty uncontainable.

But the song that my mind seems to have gotten snagged on is ‘Joy’, which sits about a quarter of the way through the album. Again, he begins the song by telling us how he ‘woke up this morning with the blues all around my head… I felt like someone in my family is dead,’ he speaks of his ‘pain and yearning sorrow’ – all of which hits you in the stomach, because such lines are wholly unexpected in a song entitled ‘Joy’.

You could read a 100,000-word long thesis on the theology of joy. Or you could just listen to this song. I think it would teach you everything you need to know.

The way Nick chooses to sign it off is to overtly tell us so. His goodbye is a direction, his epilogue is an invitation.

Despite the references to his grief, Nick recently shared that he nearly titled the album ‘Joy’. And I get why. If you think of joy as some kind of light and fluffy thing, you might not spot it. But if you, like Nick and his band of Bad Seeds, perceive joy to be something that can hold tension, confusion, and even sorrow – you will see that it is all over this project. As Nick has already taught us, faith and hope can be found amid carnage. And Nick’s new(ish)-found faith has quite obviously turned him upside down.

His wild God has clearly swept him off his feet.

The remaining songs on the album - the ones that I don’t have the wordcount to do justice - they take God/death/life, and they ponder them from every angle. There is a childlike wonder to this album, a pure kind of excitement. The kind that you'd think would be irreconcilable with the realities of grief but is somehow able to sit right alongside it. Nick isn’t trying to explain the God that he has found, or the ‘conversion’ he’s experienced – he’s just celebrating it, and inviting us all to listen.

He's simply loving God and enjoying being loved right back. It really is all very ‘Julian of Norwich-esque’. It will offend you if you try too hard to put it into a neat box.

But then there’s the last song, which is where I’ll bring this gush-a-thon to an end. It is a hymn. Like, an actual, albeit tweaked, hymn – the last song is a rendition of ‘As the Waters Cover the Sea’.

All of a sudden, there’s a gear change to grapple with. Nick is placing himself in a church, he’s tying himself to a particular religious tradition, he’s joining a particular community and affiliating with a particular history. It turns out the God of whom he speaks is not abstract, he’s the Christian God. You’re reminded that you’ve been eavesdropping on a man who has lost his son, conversing with a God who lost his too. The lyrics have been hinting at this all the way through the album, but the way Nick chooses to sign it off is to overtly tell us so. His goodbye is a direction, his epilogue is an invitation. He is basically saying -

If you’re intrigued by the Wild God, here is where precisely I have found him…

And this kind of religious specificity being used to tie up an album so full of metaphor and mystery. An album I thought I had worked out, an artist I thought I had finally cracked, a message I thought I had deciphered…

… Oh, never mind. Never mind.