In the first article, I painted a picture of the ordinary person using modern technology, for example, social media on a smart phone. I noted that advocates for modern technology seem to have two basic principles: that technology is natural and neutral. In this next article I want to introduce the philosophy of Martin Heidegger and show how he pushes against these two basic principles and invites us to think again about modern technology. Heidegger’s instinct, as a twentieth century philosopher, is to be suspicious that things are not as they seem, he casts his suspicious gaze over modern technology and sees a way of being that technology encourages that exists underneath the technologies that we use every day.

What Heidegger wants to show us about modern technology is not related to specific concerns about particular technologies but instead a general suspicion about the ‘essence’ of technology, or, you could say, the spirit of technology. He doesn’t want us to immediately jump to pragmatic questions about how to use technology, as if the primary question is how to make any given technology better or more moral. Instead, Heidegger wants us to take modern technology together as a whole and ask, “What is the essence of this?” Heidegger’s contention is that “technology is not an object or set of objects, nor a way of handling objects with tools, but a form of being the world. It is not something we choose to refuse, but the environment in which modern humans come into existence.”

Heidegger argues that underneath any piece of tech that we might use in our day-to-day lives, technology at its core has already completely changed the way that we as a society understand and interact with the world and everything in it. We live in a technological age and as members of a technological society and so we have been shaped by (to use Christian language, we have been ‘discipled’ by) the spirit of the age to see the world around us. Heidegger suggests that we now see the world as broken down into useable bits that can be categorised and reformed to suit our needs. As Mark Wrathall puts it, the essence of technology is to train us to “experience the world as calling on us or drawing us. To transform everything into stock pieces, so that they can be placed into a vast inventory of options.”[2] Growing up in a technological society means that we see the whole world as an Amazon warehouse a place of seemingly limitless options that can be called upon depending on our needs and quickly delivered.

A piece of technology such as the smartphone points to a wider ‘spirit’ of technology which intends to position everything, even human beings, as replaceable resources within a larger system.

The central word that Heidegger uses to describe the essence of technology is gestell which is not an easy word to translate into English, but two possible translations would be ‘positionality’, or ‘enframing’. His point is that the essence of technology is to remove objects, people, and things from their natural environment and position them so that they might become useful, a resource, available for our manipulation. When Heidegger says that the essence of technology is gestell he is pointing to the way that modern technology extracts objects from their contexts and turns them into a quarry to the plundered. There are of course obvious ways in which humanity has always extracted resources from the natural world: we have always quarried for energy (coal, oil etc) or chopped down forests for wood. By claiming that the essence of modern technology is gestell, Heidegger wants us to notice that in the modern world, it’s not just quarries or forests that we mine for resources but now anything and everything can be turned from being a singular object in the world into a recourse for extraction. Everything has become what Heidegger calls “standing reserve.”

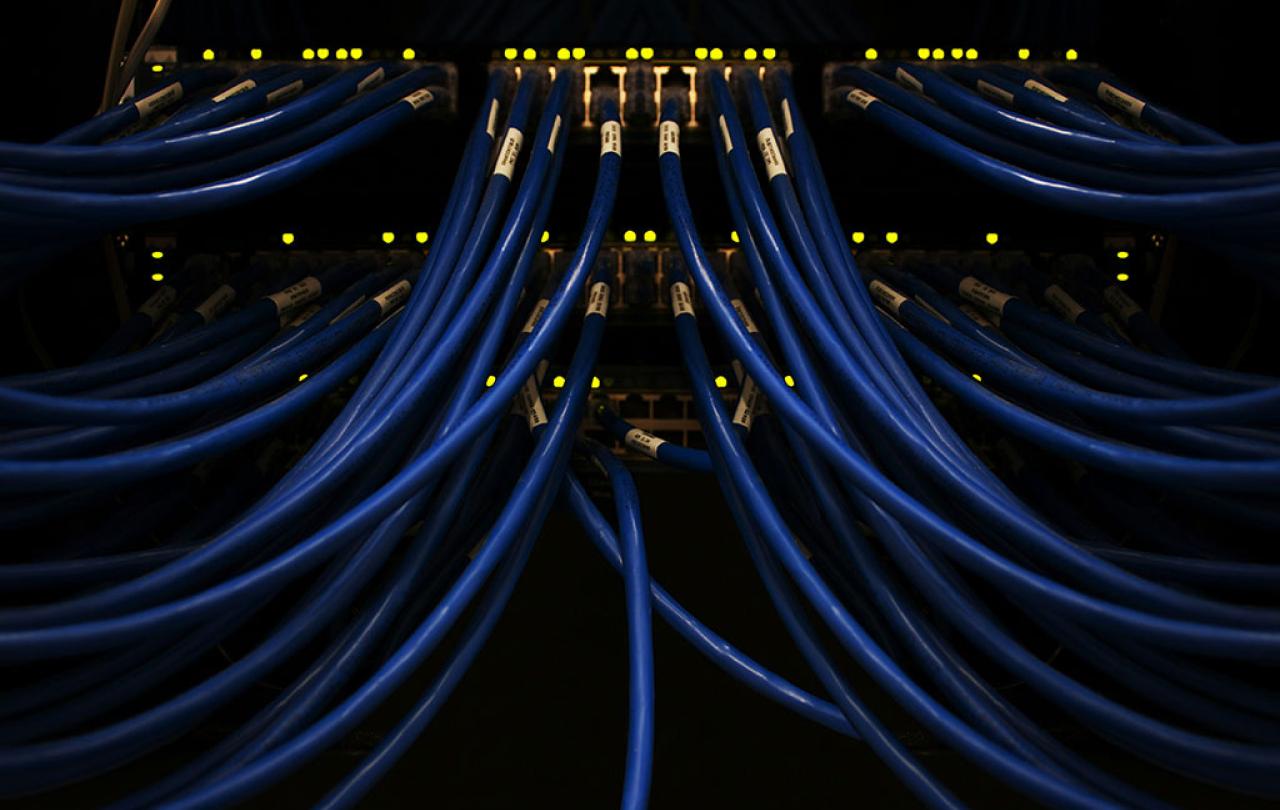

Think again of a smartphone, it is just one of the billions of devices that sit on shelves or, having already been purchased, live in someone else’s pocket. Inside each device are thousands of transistors and circuit boards each of which again are stockpiled in warehouses ready to be replaced if needed or used for some other purpose. Your phone is connected to a network of nodes each of which can be replicated or replaced if needed, no node is unique. Your latest phone has no unique or prize relation to you, it’s just the latest upgrade which will be recycled in a year or two when the next upgrade becomes available. The person from whom you bought the phone is equally replaceable, just a faceless employee completing a set of controlled and pre-arranged tasks that are designed to be completed by anyone and no one in particular. Likewise, you as the consumer are considered to be little more than “standing reserve” by the companies that supply you with your smartphone and access to their networks. One of many millions of nodes in their system that has been analysed so that your preferences can be expertly mapped to the range of services that they provide. Within that system, you are completely replaceable. A piece of technology such as the smartphone points to a wider ‘spirit’ of technology which intends to position everything, even human beings, as replaceable resources within a larger system: “Every item within this standing reserve is reduced to a position, actively waiting to be called on. Heidegger insists this is no judgment on the radio, the internet, or the smartphone user. It is just the way in which the essence of modern technology interacts with humanity… Heidegger provides a diagnosis of our modern age and the way in which we humans have placed ourselves under the sway of modern technology, as a resource standing within a network which seeks, ultimately, to place, represent, and think of every entity as an object within an all-encompassing system.”

Let’s return to the original thought experiment at the start of the first article: a mother playing with her child, who immediately reaches for her phone to capture the moment when her child does something particularly cute. An advocate for modern technology, like Steve Jobs, may look at that interaction and see only the benefit: a mother wanting to remember a beautiful moment with her child extends the capacities of her brain using a digital tool to aid her memory. But Heidegger would be more suspicious, he would look at that moment and argue instead that the essence of technology is to turn everything, even a precious moment with a cute baby, into a resource to be used at a later date. The unique moment of joy and delight between parent and child becomes caught and codified such that it can be found and replayed at will or easily replicated to send to others. At the extreme end of the spectrum are so-called content creators who reduce themselves to just another resource to be harvested on social media.

So that is Heidegger’s diagnosis of our technological age, in the final article in this series we will consider Heidegger’s solution and consider what a particularly Christian response to Heidegger’s diagnosis might look like.