Reconciliation is the key theological motif that runs through the scriptures and across Christian Tradition - Reconciliation between God and humankind, reconciliation between human beings across the cultural, social, political, ethnic and economic divide, reconciliation between our warring selves within us.

Paul’s writings form the earliest documented texts in the New Testament canon. His writings are full of references to God’s reconciling work in Christ on the cross. This theme, however, needs to be read in terms of Jewish thought. This will correct the over-spiritualising of this in Christian practice.

To make sense of the notion of reconciliation one also must understand the Jewish antecedents that inform Paul’s writing, given Paul himself was a Jewish man. In the Hebrew scriptures and in Jewish thought, atonement and salvation are collective and corporate concepts. This is very different to much of what constitutes post-Reformation Evangelical Protestantism where the emphasis is on individual salvation in Christ, by grace, through faith.

The Hebrew Bible traditions of the Sabbath and Jubilee were moments for system re-set and dismantling inequalities which had accrued.

Essentially, being in right-standing with God necessitated that one should be in right relationships with others. In fact, one could argue that it appears to be the case that one cannot be in a right relationship with God unless you were doing right by the other. The above can be seen in the Old Testament book of Leviticus. The early verses of its sixth chapter clearly state the notion of restorative justice for that which was wrongly taken and used, which is described as a “sin against God”.

One can also see this concept or formula evident within the book of Deuteronomy 15:12–18. The key is verse 12 which states:

“If any of you buy Israelites as slaves, you must set free after six years. And don’t just tell them they are free to leave – give them sheep and goats and a supply of grain and wine.”

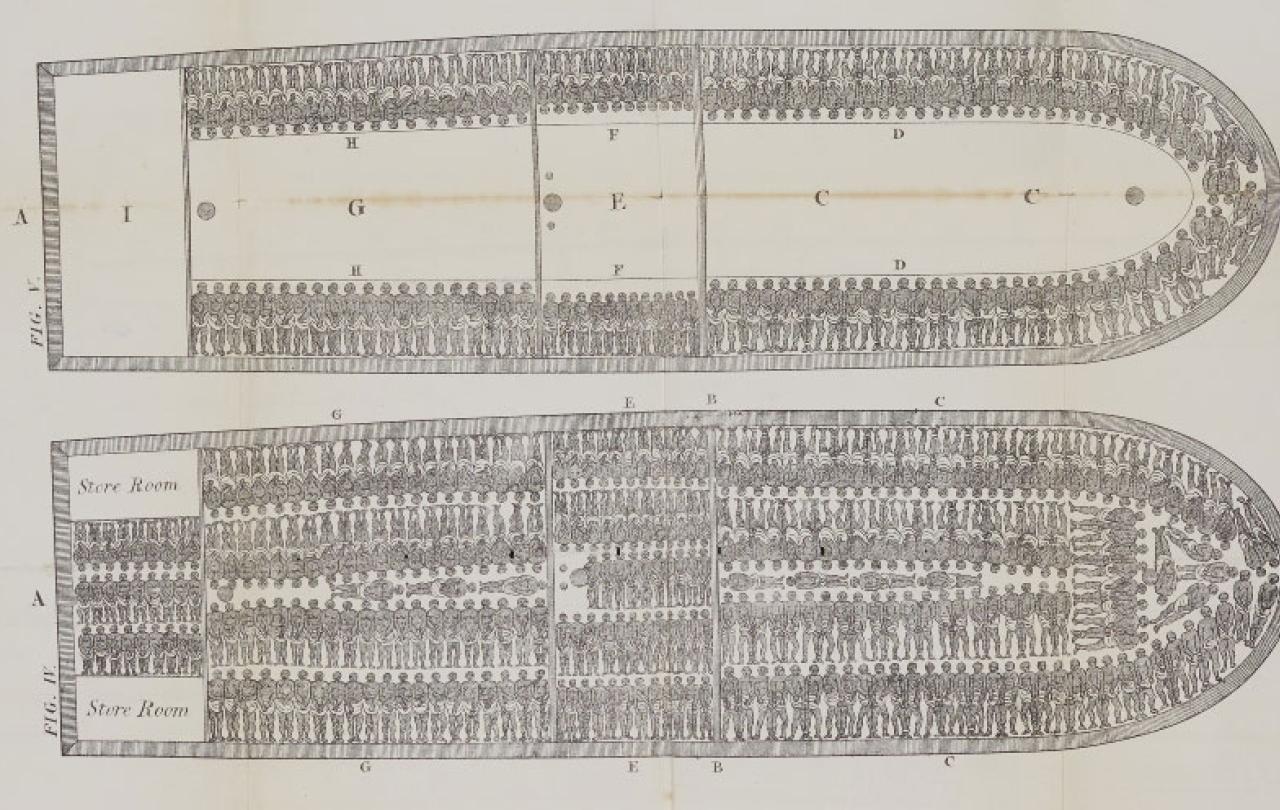

As Peter Cruchley’s work on the Zacchaeus Tax campaign has shown, the Hebrew Bible traditions of the Sabbath and Jubilee were moments for system re-set and dismantling inequalities which had accrued. They were moments of breaking the cycling, ongoing basis of debt and economic enslavement. It’s worth reminding ourselves that not one penny has been given to any of the descendants of enslaved Africans for the wrong done to them and yet Christian communities in the West still want to talk about redemption that is affirmed by their Judeo-Christian roots!

Understanding the scriptures in their historical context enables Christians to discern a theological pattern for using money and other resources for enacting restorative justice. Modern interpretive theories on how we read biblical texts take full account of the fact that the New Testament was written within the context of the Roman Empire, where the Emperor claimed divine honours which faithful Jews could not affirm. Today’s reader must recognise that the context in which ALL of the New Testament canon was composed was one that echoed to the restrictive strains of colonialism and cries for justice against oppression. Judea, in which Jesus’ ministry was largely located, was an occupied colony of the Roman Empire.

Contemporary scholars have shown that in the Jewish tradition, issues of reconciliation, redemption and salvation have a corporate ad a collective dimension to them as well as an individualistic one.

Scholars such William R. Hertzog II have shown the extent to which wealth in the Roman Province of Palestine was always connected with economic exploitation. So, when Jesus challenges the ‘Rich Young Ruler’ to follow him, he says this in knowledge that the young man’s accumulation of wealth was not amassed in a neutral context. The reason why this encounter is so compact is because both the Rich Young Ruler and those first hearers knew the expectation of how he should behave.

The Three Cs (commerce, civilisation and Christianity) were the underlying rationale on which the British Empire was based. The Three Cs were coined by David Livingstone (a London Missionary Society ‘Old Boy’) in Oxford in 1857. The exporting of Christianity via the European missionary agencies in the eighteen and nineteenth centuries was largely undertaken under the aegis of empire and colonialism. Christian mission, therefore, has had a difficult relationship with non-White bodies or the ‘subaltern’ for centuries as they are the ‘other’ and have been exploited for economic gain. There was no ethic of equality between missionaries and the ‘natives’.

One can see that Jesus’ teachings around wealth and its relationship to discipleship and living the “Jesus way” has political and economic implications. Scholars such as Musa W. Dube, Catherine Keller, Michael Nausner and Mayra Rivera, have all shown the similarities between first-century Palestine, the slave epoch of the sixteenth to eighteenthcenturies, the eras of colonialism and our present globalized, postcolonial context. Each context is based upon imperialistic/colonial expansion, capital accumulation, forced labour and exploitation of the poor by the rich.

Pharaohs on Both Sides of the Blood-Red Waters is the title of a 2017 book by the famed anti-apartheid activist and scholar Allan Boesak, who reflects on the contemporary ‘Black Lives Matter Movement’ largely in the US and post-Apartheid South Africa. In this context he speaks of the corporate reality of ‘Cheap Grace’ as outlined by the famous German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer. The West has attempted transformation WITHOUT sacrifice or restorative justice. Bonhoeffer chided Western Christians for wanting to have discipleship without radical commitment to God’s word, and forgiveness and redemption without struggle and sacrifice. Boesak reminds us that there is no redemption without the cross. Reconciliation must cost us something!

Due to the influence of post-Reformation Evangelicalism, we have largely interpreted Jesus’ words in a purely individualistic way. Contemporary scholars have shown that in the Jewish tradition, issues of reconciliation, redemption and salvation have a corporate and a collective dimension to them as well as an individualistic one.

I believe that institutions like the Church of England can set a prophetic lead to other Christian institutions, and beyond it, to other civic bodies and indeed governments. ‘Cheap Grace’ NEVER leads to redemption and reconciliation. Without restorative justice there is no reconciliation, and the mission of Christ is diminished.