“Anyone can see that our economic system is broken.”

This is the conclusion of Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics, and her assessment has garnered positive endorsements from figures as diverse as George Monbiot, Andrew Marr and Sir David Attenborough.

Yet to judge by the discussion surrounding the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement, our political class is not included in this broad perspective that Raworth claims. In what is widely understood as the early skirmishes of an election campaign, anticipating the moment when the country’s voters have another opportunity to indicate the direction of travel they hope for, the focus is on who will be better or worse off by this or that tax cut or benefit change. If anything is broken it is not the economic system but something like ‘the government’s economic management’ (Labour) or ‘public sector productivity’ (Conservative).

If you are worried, as Raworth is, by “relentless financial crises,” “extreme inequalities in wealth” and “remorseless pressure on the environment” then it seems that both the government and the opposition believe that the solution is more economic growth, albeit with some barely discernible differences in fiscal and regulatory policy.

Our contemporary political discourse is dominated, regardless of party, by the mainstream economic paradigm in which the market generates economic growth and the state functions to keep things on track by taxing and redistributing some of the surplus to those who for whatever reason didn’t do as well as others in the process. It also provides some additional incentives to business and other organisations to act in the public interest, for instance by subsidising green energy or taxing fossil fuels. Both parties, it seems, support this approach. The difference between them concerns how best the state manages the economy to get the most out of it, how the resulting surplus is distributed, and what kind of further incentives are needed.

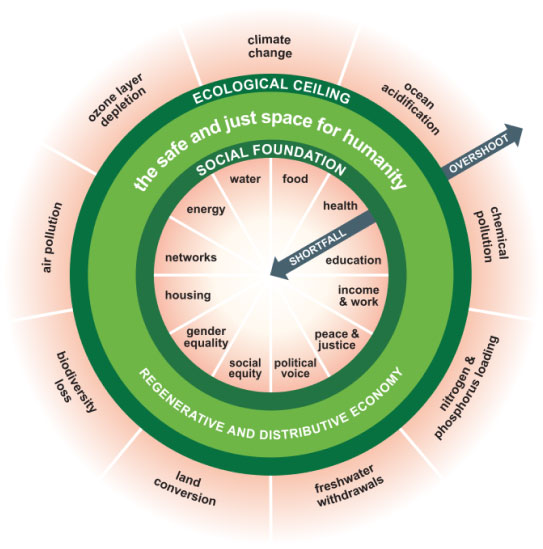

Visualising doughnut economics

For Raworth, on the other hand, the first thing to ditch is the assumption that economic growth is the right goal to pursue. The ‘doughnut’ of doughnut economics is an alternative to GDP as a measure of progress. It name is derived from the visual depiction of the idea of an economy that operates in the space within two limits – ensuring the human rights of each person on the one hand, and staying within the means of the planet on the other. This concept refuses to conceptualise the economy as a closed system in distinction from the social and environmental systems on which it depends.

Raworth also wants to shift the emphasis away from the individual rational chooser of economic theory toward a more social understanding of human flourishing. And in direct contrast to the mainstream paradigm sketched above, in which the market’s job is to deliver economic wealth and the state’s job is to worry about distribution and regulation, Raworth wants an economic system designed from the outset to ensure a more equal distribution and to actively regenerate the environment.

The economic system itself is like an engine that can be put to whatever purpose you want. It generates wealth and wealth can be put to all kinds of uses, good or bad.

How might we evaluate this? Nobody disagrees that financial crises, extreme inequality and environmental damage occur and are bad. A good number of mainstream economists find Raworth’s aims laudable and worth pursuing, because we do need a better measure of success and improved models of human behaviour and ways to incorporate and limit externalities like carbon emissions. Yet they also find her analysis of economics a caricature, as many of the developments in economics over the last few decades seem to be ignored.

For her harshest critics, Raworth fails to give due credit to our current economic system for the incredible reduction in global poverty that it has already enabled, provides very little by way of actionable policy ideas, and is full of erudite but wishful thinking.

Yet the popularity of Doughnut Economics reflects a deep sense amongst many of us (some mainstream economists included) that something is seriously wrong, alongside an instinctive identification with the kind of values and changes that Raworth seeks.

The vital question is: what is our economy for? If we can get a better sense of what purpose we want the economy to serve, it may prove easier to identify whether it is achieving that, or is in some sense ‘broken.’

But to ask this question is immediately to step away from the mainstream paradigm that dominates our public discourse in framing the economy. For mainstream economics, questions of purpose are ethical questions and those questions are explicitly left to the actors within the economic system and the state acting on their behalf. The economic system itself is like an engine that can be put to whatever purpose you want. It generates wealth and wealth can be put to all kinds of uses, good or bad.

These ancient texts suggest that our mainstream paradigm is seriously adrift if it imagines that our economic system is morally neutral.

For many people the idea that the economy itself can be separated from ethical questions will automatically raise an alarm. Certainly, for Christians it ought to. The Bible firmly resists the idea that wealth and its generation is morally neutral. Even the most superficial reading of the Scripture alerts to the inherently spiritual and moral quality of economic activity. Fruitful work is part of what it means to be made in the image of God in the garden of Eden. The product of work is offered to God in worship. The Law is full of commands to deal justly, use fair weights and measures, consider health and safety in the building of a house, and give yourself, your family and your animals a rest (to name but a few). Jesus tells us that you cannot serve both God and money. The pictures of the New Creation in both Old and New Testaments include economic imagery – The Old Testament book of Micah envisions an end to war with everyone living “under their own vine and fig tree” (a vision of peace and economic flourishing) and the New Testament book of Revelation depicts the product of human work being offered up in worship before the throne of God.

Overall the Bible sees the economic, social and environmental dimensions of life as interwoven and interconnected. Take the Sabbath, for instance. It is not only workers who get (or are commanded to take) a Sabbath once a week. The command extends to the whole community - and even to animals. Every seven years, the Sabbath Year provides a rest for the land and for those struggling with debt – the land must be fallow and allowed to regenerate, and all outstanding debts cancelled. Sabbath and Jubilee are deeply intertwined (the Jubilee was effectively a sabbath of sabbaths, taking place after seven sabbath years) and the Jubilee was the theological paradigm chosen by Jesus to explain his own mission and ministry. Quoting the prophet Isaiah, he said:

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the captives, recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.”

These ancient texts suggest that our mainstream paradigm is seriously adrift if it imagines that our economic system is morally neutral. And Raworth is closely aligned with the biblical vision insofar as she insists on the importance of an economy that exists not for its own sake, in some independent sphere, but explicitly to enable people, communities and creation to flourish together. We need to ask what our economy is for. And this is as good an answer as you might find.