A recent survey of belief in Britain yielded a confused result. Belief in God has declined, yet belief in the afterlife has risen. People are less likely to see themselves as religious, and don’t pray much, yet continue to trust religious organisations. We are caught between belief and unbelief.

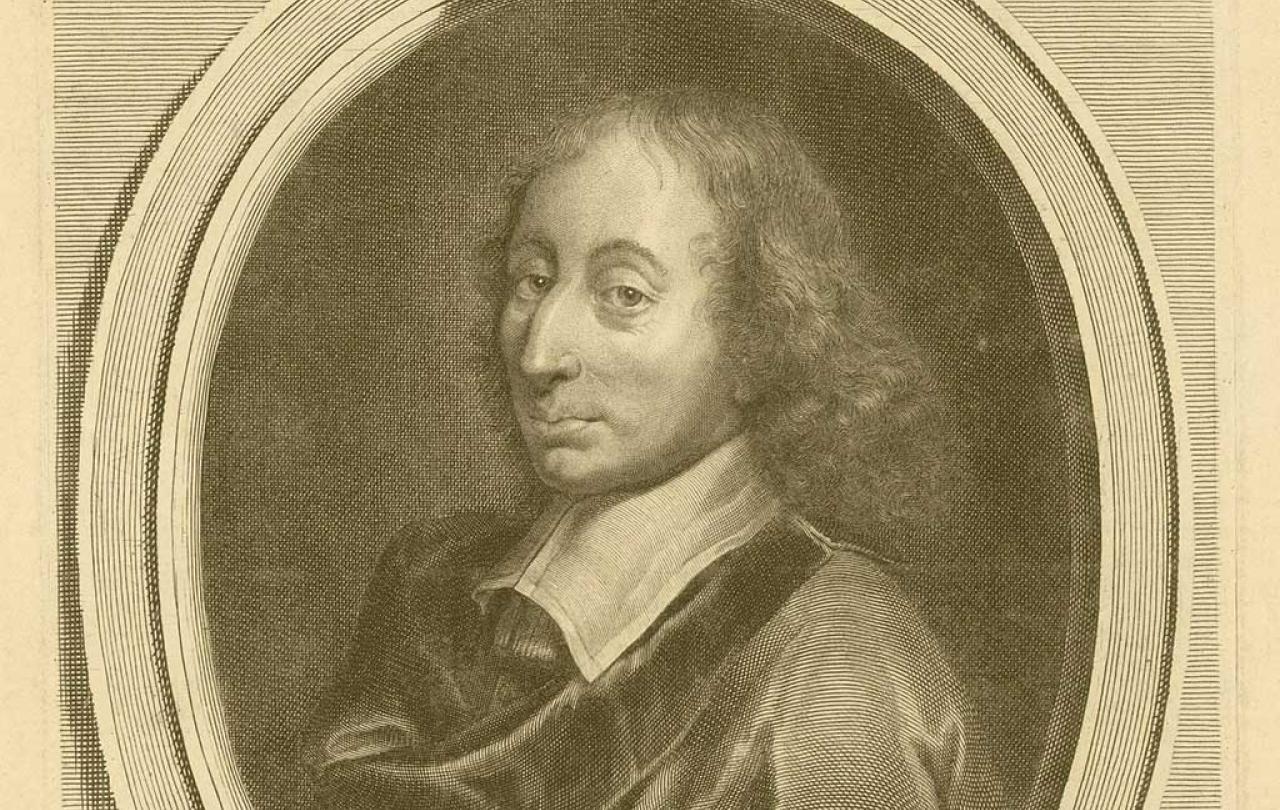

A guide to our times might just be found in one of the greatest geniuses of the modern world, born 400 years ago this year – on 19th June. Blaise Pascal died before he reached the age of 40, and lived much of his life in chronic sickness, but in less than four decades he became one of the most famous and celebrated minds in France, conducting ground-breaking scientific experiments in a range of fields of physics, laying the foundations of probability theory, building one of the very first functioning calculating machines - a precursor to the computer, playing a key role in a start-up company which provided one of the first urban public transportation systems in Europe, and writing one of the great classics of satirical French literature – the Lettres Provinciales.

Yet he is best known today for a book that he never finished.

The thoughts

Pascal was born into a well-to-do middle class French family, the son of a tax official in the civil service. Although his mother died while he was still a toddler, his father recognised the extraordinary talent of his young son and decided to home-school him along with his two sisters. Theirs was a fairly conventional Catholic family and yet in time they came under the influence of an intensely devout movement in 17th century French religion, the Jansenists. Taking their name from a Belgian Bishop, Cornelius Jansen, their world-denying piety and ongoing feud with the powerful Jesuits made them a controversial group in the landscape of French religion at the time.

Blaise himself had a somewhat distant relation to the Jansenists, being much more interested in his investigations into physics, geometry and mathematics that began to raise eyebrows all over Europe. That was until a dramatic event on the 23rd November 1654. Not much is known about this life-transforming experience, but for two dramatic hours late that evening, Pascal experienced a profound encounter with the God who had always been vaguely in the background of his life but not a compelling presence.

The change was radical if not total. He didn't give up on the life of the mind, but instead started to think deeply about how to change the minds of the many cultured despisers of religion he had come to know through his scientific researches and through his exposure to the fashionable salons of Parisian life.

As various thoughts on this project occurred to him, he began to write them down on scraps of paper. Some were brief enigmatic sentences that clearly made sense to him but to no one else; others were a paragraph outlining a radical thought; some were longer, more reasoned pieces, carefully developing an argument. He died before he was able to finish this great Apology for Christianity and left behind a haunting, tantalising collection of fragments, which were collected together by a group of friends after his death and published as the Pensées de M. Pascal sur la Religion et sur Quelques Autres Sujets – or Pascal’s Pensées, for short.

Pascal had a problem in trying to do this. He knew from his own experience that piling up arguments as to why God might exist, or that you should think about God once in a while, don’t get you very far. They tend to produce at best a lukewarm, distant kind of religion that is more of a burden on the soul than a liberating presence, the kind of passive, slightly reluctant faith that he had held until that dramatic November night. They also point you towards the wrong God, the ‘God of the philosophers’ as he described it in his famous phrase, a God who is the logical conclusion of an argument rather than a living, breathing, haunting presence, both majestically distant and yet hauntingly present at every moment. He also knew that you can't manufacture profound experiences of the presence of God such as had happened to him. It was at the heart of St Augustine’s teaching, as conveyed through Jansenism, that only God's grace can shift the stubborn human heart, kindling in it a love for God that until that point was impossible to imagine, let alone experience.

Pascal was fascinated by our capacity to distract ourselves from the bigger questions of life and death. Is there a God? Who am I? Which religion is true, if any of them? What happens after our brief lives are over? If we are a tiny speck of life on a tiny insignificant planet within the vast expanses of space that were beginning to be discovered at the time, what possible significance can we have? How do you explain the monstrous contradiction of human beings who have the capacity for compassion, understanding and greatness and yet also for cruelty, bestiality and shame?

In the room

These are all big questions on which our eternal destiny depends, and so should occupy our minds day and night, and yet we have a remarkable capacity to distract ourselves from thinking about them. Silence and inactivity are unbearable to us and so we fill our time with (in his day) hunting, cards, conversation, tennis. As he put it, “the sole cause of a man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.” He would have marvelled at our age with Twitter, TikTok, 24-hour TV and the myriad ways we find to divert ourselves during the most fantastically distracted age there has ever been.

And so Pascal tries to unsettle his reader, trying to stir up the instinct to consider deeper questions. Yet he still knows that even when we do start thinking about these things, we get muddled. Is there a God? Religious people say Yes; Atheists say No. Pascal knows enough of science to know that it is not capable of adjudicating on such questions, that evidence of miracles or biblical prophecies are ambiguous, and certainty is impossible to find. So what do you do when you're intrigued by religion but there isn't enough evidence to push you across the line to be a Christian? When one moment you're convinced God is real, but the next you doubt the whole thing?

Maybe you give up on it - get back to scrolling through TikTok videos, watching the football on TV, musing over Harry and Meghan? Yet Pascal says you can't just do that. You have to live your life as if there is a God and you need saving, or as if there isn't, and you don’t. And you and I will face the consequences of that choice after our lives are over, one way or the other.

This is where one of Pascal's most distinctive moves comes in. Among his sophisticated friends, were many who spent hours betting. Pascal had already done a playful bit of work working out the odds on certain bets, and what the likelihood was all victory and defeat in an uncompleted game – for cricket fans, a kind of early Duckworth-Lewis method for gambling with dice.

The wager

Pascal’s argument runs like this: If you were strictly speaking betting rationally on the odds, then you’d always bet on God. If you bet on God not existing, and there is no life after this one, and you’re right, you don’t gain a great deal – just a few brief years’ pleasure while you’re young and fit enough to enjoy it. But if you bet on God existing, and there is a life beyond the here and now, and you end up being right, you stand to gain a huge dividend – eternal happiness in the presence of God – all this for the sake of a tiny stake – a life of discipline and self-denial for a few years here on earth. So looking objectively and rationally at the odds on offer here, a betting man or woman would always bet on belief. But Pascal knows that we don’t think that way. Why? It’s not because we are being rational; it’s because belief is inconvenient, we would rather there was no God, it costs too much, and we just don’t want to believe.

So if the evidence is inconclusive, and you're aware that your own motives are mixed, then what do you do? Pascal thinks we are creatures formed by habit. So his advice is to start living as if it's all true even if you're not sure whether it is. Wise people in the past “behaved just as if they did believe, taking holy water, having masses said and so on….” Start practising the habit of daily prayer to God even if you're not sure whether he's listening or not. Start treating each person you meet each day as if they're not just another inconvenience in your path but someone precious, loved by God and created in his image. Start going to a church regularly meeting with other Christians for that kind of mutual strengthening of faith that only being with others can bring. Take the bread and wine of Holy Communion as if they really are the gift of Christ’s presence to you. And see what happens.

Start living

Pascal reckons, sooner or later, as had happened to him and countless others, belief will surely follow behaviour. Start living as if it is true and slowly (or perhaps dramatically) you will realise not only that it is true, but that it brings far more joy and delight than you ever thought possible.

T.S. Eliot once wrote:

“I can think of no Christian writer… more to be commended than Pascal to those who doubt, but have the mind to conceive, and the sensibility to feel, the disorder, the futility, the meaninglessness, the mystery of life and suffering, and who can only find peace through a satisfaction of the whole being.”

If we live in a culture that profoundly doubts God, yet which at the same time longs to find happiness, then perhaps Pascal is just the kind of guide we need.