I’ve been re-reading Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front in the run-up to Remembrance Day. Remarque, born in Westphalia in 1898, uses his own experiences of the horrors of the Western Front to paint a gut-wrenching portrait of its futility and suffering, seen through the eyes of 20-year-old Paul Baum.

It had been towards the end of this First World War that Hiram Johnson, Republican Senator of California, observed that ‘the first casualty when war comes is truth.’ This is precisely Paul’s experience.

The newspapers delivered to the soldiers at the Front are hopelessly, naively, offensively optimistic. They present a painfully, laughably discordant tissue of lies that deny the most basic truths of daily experience. When Paul goes home on leave, truth is even harder to find. His remote father only wants to hear tales of glory and courage and well-fed soldiers. His blabbering former teachers - the very ones who had cajoled his whole class to sign up - are patronising, ignorant and opinionated on the best route to victory. They literally have no idea, and worse, they don’t want to know.

It’s only when he’s taken to a Catholic Hospital after an injury that Paul stumbles on an agonising truth -

‘A hospital alone shows what war is.’

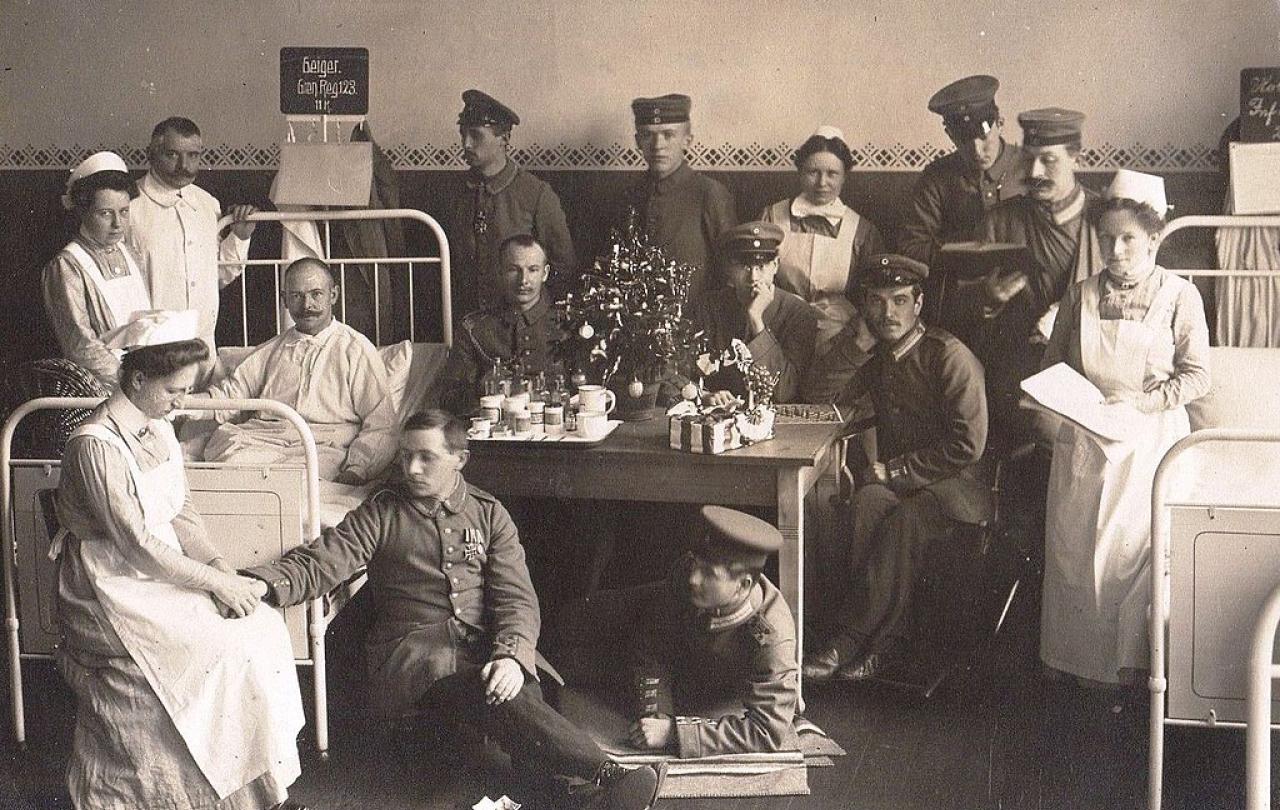

Paul’s vivid description of life on the wards backs this up. He witnesses the unceasing production line of shattered bodies tumbling into every available space. He’s warned against ‘The Dying Room’ which is conveniently, practically, located next to the mortuary. He catalogues the surrounding wards - ‘abdominal and spinal cases, head wounds, double amputations, jaw wounds, gas cases, nose, ear and neck wounds … the blind … lung wounds, pelvis wounds, wounds in the testicles …’ He’s grateful for the gentle, joyful kindness of Sister Libertine, ‘who spreads good cheer through the whole wing.’

This hospital is more eloquent on the theme of the futility of the fighting than any newspaper article or speech, censored or otherwise.

For much of my adult life grainy videos of precision-guided bombs and leaders pounding their fist in defiant rhetoric have been the go-to guides to tell us the truth about modern warfare. I trust these sources less than ever, as I recall my instinctive respect for the ambulance drivers, nurses and doctors on the front-line - wherever it may be - marvelling at their courage and truth-telling and even-handed humanity.

Their voices are shamefully drowned out in the world’s conflict zones, dwarfed by propaganda as insulting and truth-lite as the newspapers that doubled as toilet paper for both sides on the Western Front. And I cringe at the thought of what Paul and his young comrades would’ve made of hospitals - those oases of truth - becoming the targets of today’s bombs, missiles and drone strikes.

We, rightly, remember the First World War as the very epitome of futility - Paul and his generation saw this truth far more clearly than we do. But let’s not congratulate ourselves, as we prepare for Acts of Remembrance in 2024, on having made any real progress in the last 100 years - hospitals across the globe’s conflict zones still tell us what war really is, if only we could hear, if only we would listen.