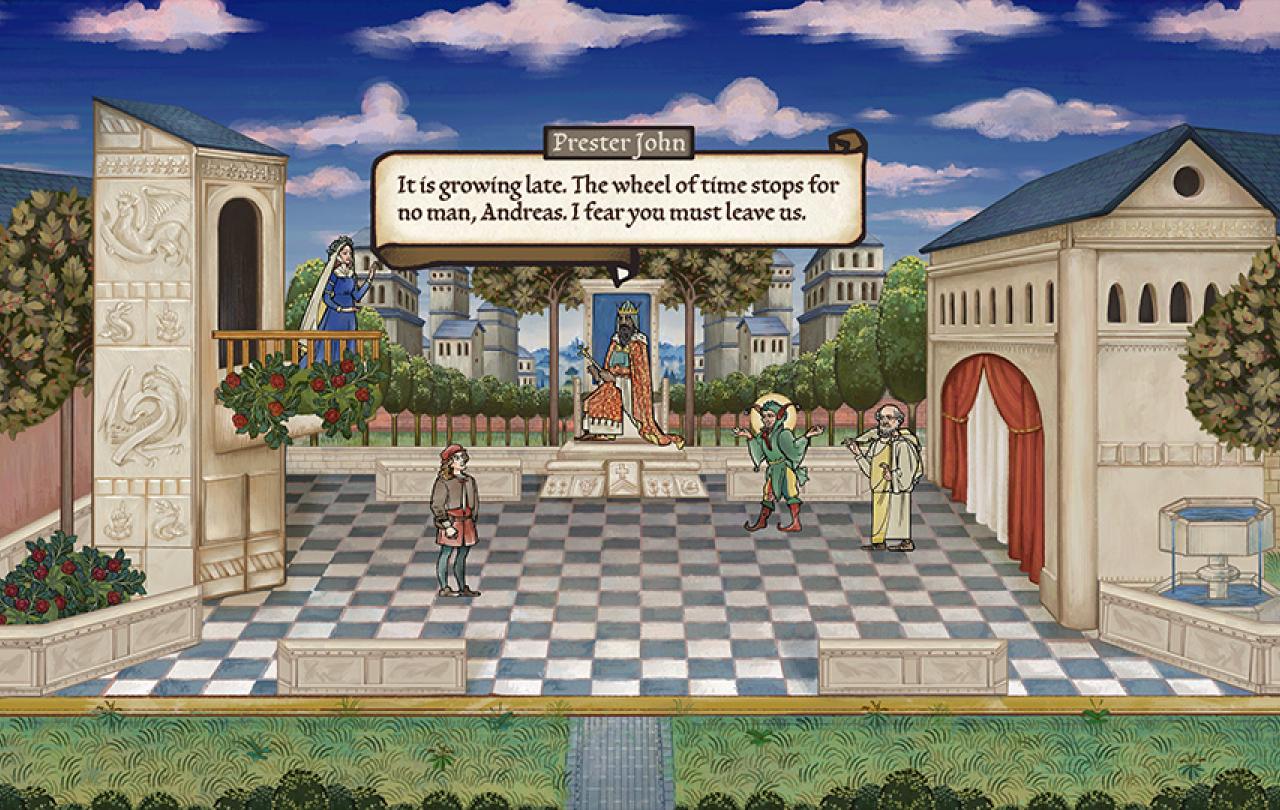

Pentiment, an adventure game set in the rural Bavarian town of Tassing between the years 1518 and 1543, transports players to a time of political intrigue, religious reform, and societal conflict. With a deep love for history based on meticulous research, the game offers an authentic look at the lives of ordinary people like peasants, monks, artisans, and farmers, and the decisions that shaped their lives.

At the heart of the game is Andreas Maler, an artisan who is hired to illustrate manuscripts in the Abbey of Kiersau. As he stumbles upon a murder, he is drawn into a web of personal conflicts that balance the different professional and societal groups of the village. Players can immerse themselves in the story and get to know the characters intimately, thanks to sophisticated design and a myriad of thoughtful details. Playing as Andreas, you feel like you are becoming an integrative part of a larger story and leaving a footprint in the village's history.

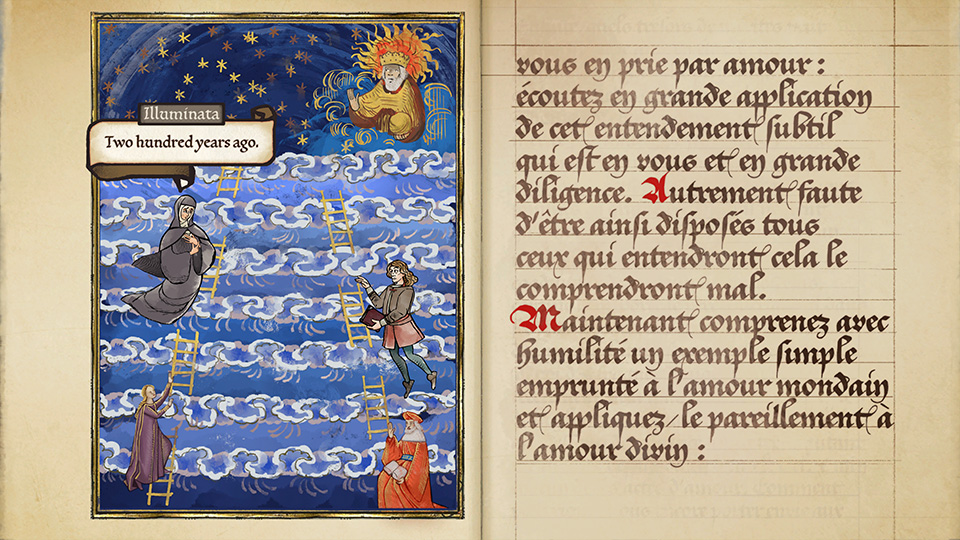

The game is beautifully illustrated and captures the essence of medieval aesthetics, making it a joy to play and a valuable educational tool. Everyday life in the Bavarian village is brought to life with attention to detail, from the food they eat to the different scripts characters are represented with. These features transform into crucial puzzle pieces to solve the murder mystery. To help keep track of the storyline and interesting info, the game provides a journal and glossary.

Pentiment feels like a playful, enjoyable, and in-depth history lecture. It is highly recommended to anyone interested in diving into a different time period – to anyone who appreciates learning not only about grand historical geopolitics but also simple, everyday life. Although it is thought of as a single-player game, it is also beautifully played with another person, with whom to explore which traits to choose, which characters to approach, and ultimately, which path to take. This game is not just for those who want to escape into a different time period, but also for those who appreciate a well-researched, multi-faceted murder mystery.

The setting of the game enhances its appeal in various ways. The 1500s were the time of the Protestant Reformation, a religious reform movement sweeping through large parts of Europe. Intersecting with it was the German Peasants’ War of 1524-1525. As you play the game, identifying with the main characters in this Bavarian town, you triangulate your position asking questions like: Where did the murder victim stand in terms of religious reform and the peasants’ demands? Where does my interlocutor stand? What position do I take to get the information I need to solve the murder mystery?

Beyond the enjoyable whodunnit, the game raises deeper questions such as: Is it legitimate to portray people and events untruthfully – that is, in a way that does not correspond to one's own knowledge – for ideological reasons or to promote a good cause? Is it appropriate, for example, to embellish the representation of local history in public space? If so, on what grounds and to what extent? What does this mean for the way we present the history of our churches? In our attempts to steer public perception, are we possibly damaging the discipline (history, church history) as well as the integrity of the positions promoted?

The name of the game is carefully chosen: Pentimento refers to ‘the presence or emergence of earlier images, forms, or strokes that have been changed and painted over.’ Pentiment is worth engaging with on more than one level.

The controls are simple, and dialogues are well done, though at times the game can be a bit confusing – accessible albeit occasionally challenging. While void of fast-moving animation and action, it is sophisticatedly made, letting the player get to know and experience each character. All in all, it comes together beautifully and deserves.

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Pentiment is available on Windows and Xbox and is published by Obsidian Entertainment.