I devour new ideas. One way to sate the appetite is dining out on Radio 4’s In Our Time archive. The show’s host Melvyn Bragg politely and firmly guides academic experts as they share their wisdom and insights with the listener. Among these great teachers, one had a title that stood out for me - Professor of the History of Early Modern Ideas. It was held by the late Justin Champion of Royal Holloway University. While I may never aspire to don his mantle, I do love the idea of, well, a professor of ideas. So much to discover and explain – to educate upon.

As well as formal academics in universities, other types of educators share that teaching load. Among them is the School of Life. A purveyor of therapy, courses and books, it has published A History of Ideas. The book is a collection of what the School calls humanity’s most inspiring ideas throughout time, ideas ‘best suited to healing, enchanting and revising us.’ Its stated goal is to answer the biggest puzzles we may have: about the direction of our lives, the issues of relationships, the meaning of existence.

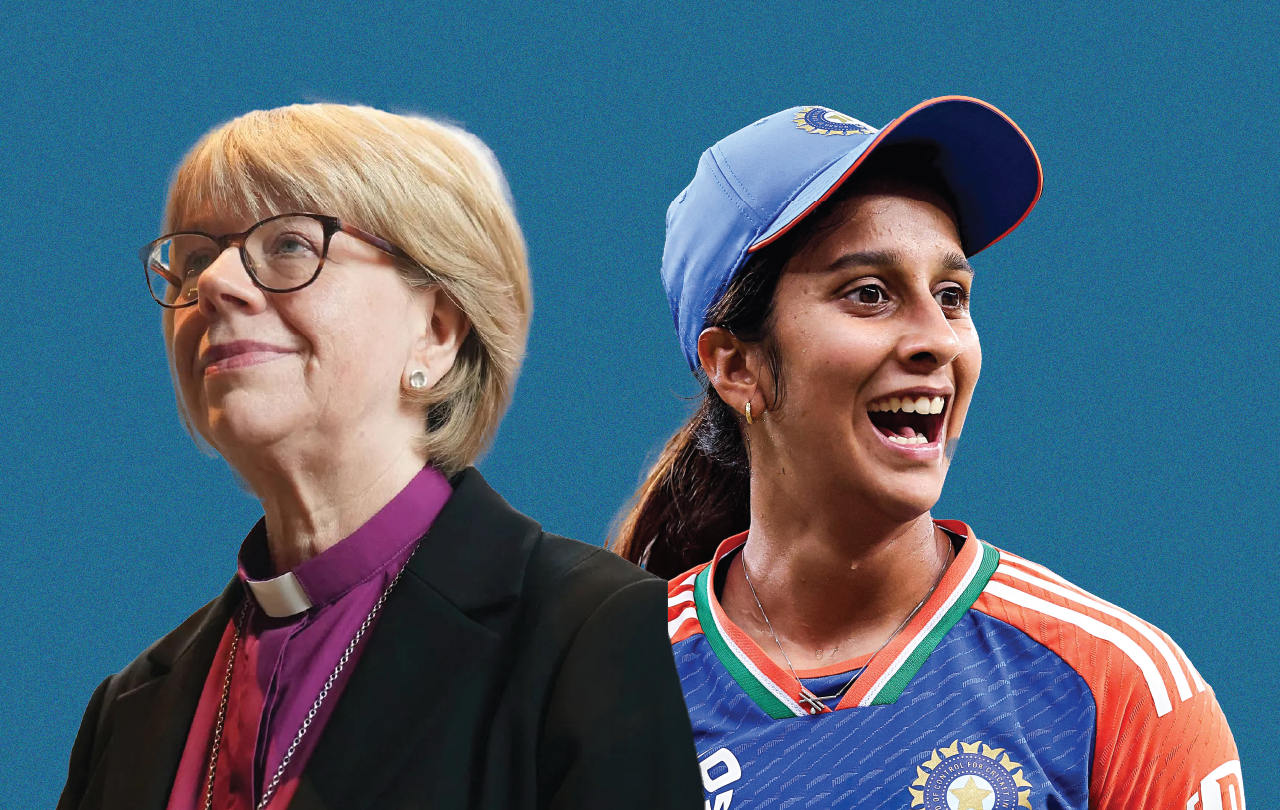

Given the School of Life was started by authors, therapists and educators, A History of Ideas could be considered its textbook, but it is no academic textbook. Instead, every idea it addresses hangs off a full-page image accompanied by essay, often based on articles the School has published.

Arranging ideas is always challenging. The book documents the history of the world’s ideas in 12 chapters. Good news for Julian Barnes, whose A History of the World in 10½ Chapters remains on top of the concise world history league by one and a half chapters. Prehistory and The Ancients, and Modernity bookend chapters on the great religions, Europe, The Americas, Industrialisation and Africa.

Within chapters, fine art, architecture and objects illustrate the ideas. Grand masters can be expected on the pages but they are joined by lesser works. Such selections serve their purpose well. The Scullery Maid, by Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, depicts the drudgery of washer work yet brings to visual life the accompanying first essay on Christianity. This is no art history exposition of some baroque high altar piece – rather:

‘Central to Christianity has been the argument about the value of ordinary people… this was a religion that never stopped stressing that God's mercy was offered to all irrespective of social status.’

Nor does it shy away from tackling what today may be seen as problematic ideas. On original sin, it asks:

‘why would it be helpful to keep this in mind? Because once we accept the bleak verdict, we are spared the risks of misplaced expectations. To know that everyone we encounter will, at some level, be flawed reduces our fury and our disappointment with this or that problematic aspect of their character.’

Wise words in an age where few can disagree agreeably.

The ideas of industrialisation are, perhaps, foreshadowed by the 18th century scullery maid’s crude washing tub. From today’s perspective, it seems that some of the big ideas haves been vigorously scrubbed away by the industrial revolution and allied revolutionary trades. However, the commentary on The Scullery Maid concludes:

‘an ideology can be said to have achieved true victory when we forget it even exists. We can tell that Christianity has been one of the most powerful movements of ideas there has ever been, in part because of how seldom we notice that it has ever had the slightest influence on us.’

Living in a ‘decade of disruption’, to quote Rory Stewart, there are many big questions being asked. Among them, “will it all be OK?" The History of Ideas is a carefully curated gallery that illustrate the big ideas helping answer those questions. Given the authors set out to curate ideas that could enchant, it may also re-enchant those asking - with that which they have forgotten exists.

A History of Ideas is published by The School of Life.

ISBN: 9781912891962