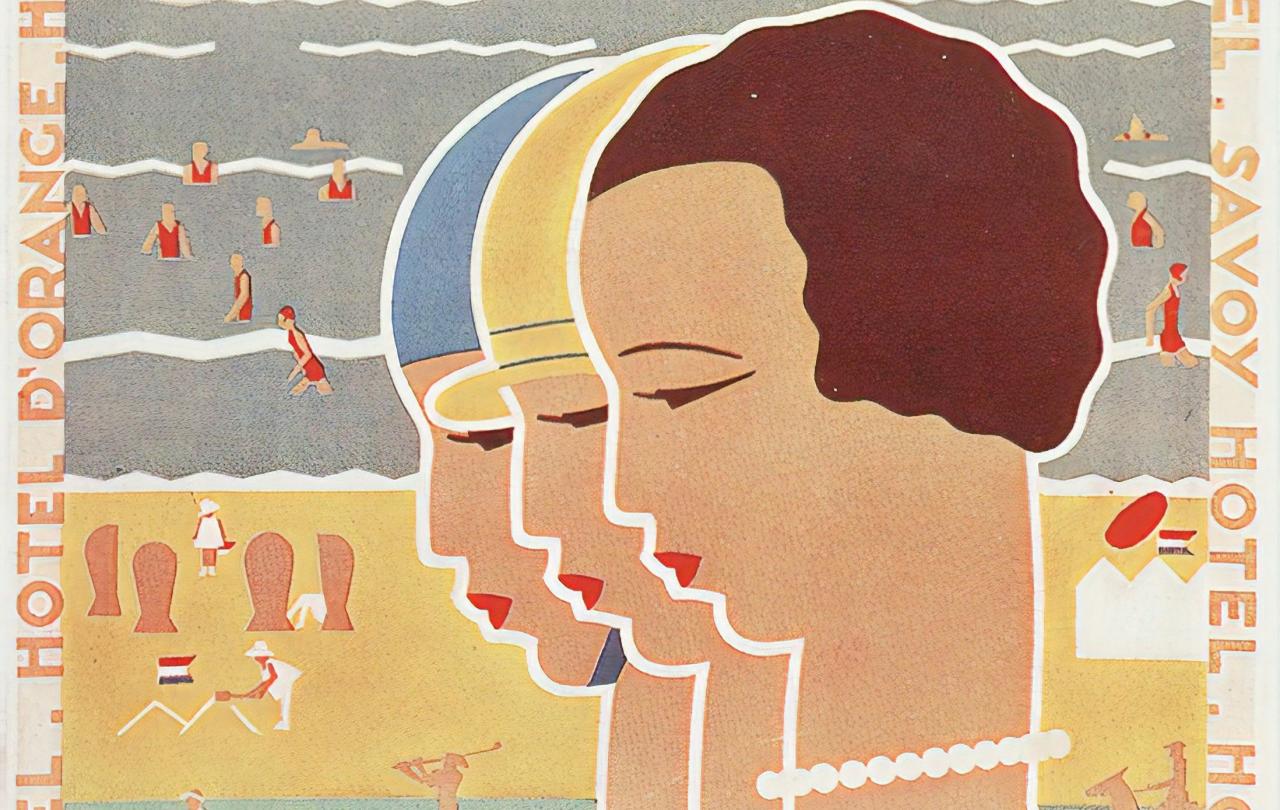

Agatha Christie, The Savoy Hotel, Cartier, The Great Gatsby, and All That Jazz sit under the gilt-edge umbrella that is Art Deco. This design movement blossomed for two decades. In 2025, Art Deco turns 100 years old. Today, it's a celebrated era for its gift to design, but what can we learn from this period, and how have the ideologies of this period stood the test of time?

Art Deco saw geometric patterns with rectilinear lines, rich jewel contrasting colours with luxury exotic materials, virtuosic craftsmanship, and streamlined expression in architecture, furniture, fashion, art, and jewelry.

On the surface, this style had many muses, from traditional African art to Cubism. It linked the discovery of Tutankhamen in 1926 with the ceramics of Japan. The bold theatrical colours of the costumes and stage designs of the Ballet Russes, also made a huge impression on Deco creatives. It infused their work with the first vibrant, intense strokes of modern design.

Over the past 100 years, we have applied Art Deco ideas in different ways, taking what we want from it when we needed to.

It was the first truly international style, yet it had distinct local expressions. American Art Deco – such as the ornate topped skyscrapers like the Empire State building, had a different expression from opulent Parisian objects such as Cartier alabaster cigar boxes.

The original Art Deco creatives sought to capture the essence of beauty refined to its simplest form. There was a focus on geometric shapes, symmetry and measured ornamentation. They wanted to remove the excess frills of previous generations and refine the design.

Under the gilt-edged Art Deco umbrella were two somewhat opposing arms – the decadent strand vs the essentialist. Today, in popular culture, we remember this period for the Roaring Twenties, excess and hedonism. The decadent strand favoured luxurious, opulent craftsmanship. Its products were attainable only by a small pool of wealthy patrons.

The essentialist strand – "Art Deco de Moderne" began with noble intentions. They prized efficiency and simplicity, characterised by geometric rectilinear designs. These creatives wanted design to respond to the changing needs of the age. They wanted great design to be accessible to more people. Both strands recognised the power of design to elevate the human experience. They invested in the endeavour to craft beauty across the entire sphere of life, from elevated factories to generous streamlined apartments.

Vogue Cup and Saucer, 1930, V&A Museum.

100 years later, the problem of accessibility of good design hasn't been fixed. Craftspeople still need to find ways to sustain a living. Handmade design from natural materials is still mainly attainable by the wealthiest. Local craftsmanship is in crisis, and many of us do not know and cannot afford artisans to make things for us from natural materials. Many skilled artisans cannot maintain workshops in our cities.

Art Deco designers may not have described themselves as hedonists, but they certainly produced goods with this dazzling class in mind. These designers had to be at ease with this world and knew how to play its game to remain commercially viable. So why did the Art Deco Age gush with an ideology of hedonism?

The philosophy of hedonism from the interwar period reflected the worldview of the so-called 'Lost Generation'. American author Gertrude Stein famously said to a young Ernest Hemingway years after World War I:

"All of you young people who served in the war... You are all a lost generation . . . You have no respect for anything. You drink yourself to death ...".

This mood was the backdrop to the literary and creative landscape of the 1920s.

When the Great War ended, people wanted to celebrate - play, party and travel, but euphoria for some turned to excess. The simple joys of living here and now became an absolute value. They had witnessed the horrors of war, the fragility of life and were jubilant, wishing to live life to the full. Knowing life could be cut short, the doyennes of the age swung into excess, supposedly breaking free of Christian values, only to find they became trapped in cycles of gratification that didn't deliver. "Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die!"

This unbridled hedonism was their feast after the plague - it was a coping mechanism. They couldn't think about the future – living here and now was a maxim underpinning this period.

The Lost Generation grasped the concept of being present in the moment, but they also discovered numbing pain was a deeply unsatisfying solution.

Fast forward a hundred years, and hedonism is still elusive and utterly unhelpful. It still has a numbing rather than a healing effect. Perhaps its modern relative is bingeing. You know what your binge is, and so does Netflix and our NHS.

What can the hedonists hijack of Art Deco teach us? Looking sympathetically on this era – hedonism appears to be a coping mechanism. Something humans have needed for aeons. "Do not worry about tomorrow for tomorrow will worry about itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own",said Jesus. The Lost Generation grasped the concept of being present in the moment, but they also discovered numbing pain was a deeply unsatisfying solution.

Ideally, the weight of grief and loss must be wrestled with, carried, shared and not buried. In great pain, it is still wiser to face it, wrestle, get help and cry out to God. In our age, we have the benefit of hindsight to know that burying trauma produces unhealthy outcomes in the long term. We have the privilege of being able to access counsellors, therapists and psychologists.

The fragility of being in the shadow of death doesn't hang over us today in the West, because we haven't had a recent World War. The closest reminder came through the COVID-19 pandemic. For a moment, we were all forced to focus on simpler things and live less frenetically.

Another ideology underpinning the age of Art Deco was the belief in the transformative power of the machine age. In this era, confidence rose in the ability of machines. Steamships, aeroplanes, automobiles, electrification and telecommunications were transformative innovations.

The rise of machines represented a break from the failed past and the move into modernity into the future. Some of the more modern leaning Art Deco designers took inspiration from the shapes of the new machines and hoped that mass production would lead to more democratic outcomes, with good design being available to all. From Art Deco de Moderne, we began to learn the beauty of simplicity. Efficiency and essentialism were prized. It was the forerunner to Modernism proper. Sadly, this aspect has been butchered over the decades and reproduced unfaithfully in architecture and consumer products. The principle of celebrating the inventiveness of man slowly evolved into something less noble. The desire to return to the essence of good design was galvanised by the need to rebuild fast after World War Two, both as a sign of triumphalism but also to give the nation decent homes. Council house homes were built quickly to rehouse the nation using cheap materials.

Today, mass production has indeed made design more accessible. More of us have access to contemporary-designed objects and clothes because they are manufactured quickly out of cheap, synthetic, non-biodegradable, toxic materials, at the sweat and tears of workers who are trapped in inhumane conditions, rarely seeing sunlight or fair wages.

Nevertheless, 100 Years of Art Deco design has shown us that quality still endures over quantity. The Art Deco legacy of brilliant buildings made of robust materials, with subtle virtuoso ornamentation, has survived the test of time. Though more of us can enjoy contemporary design at affordable prices, I doubt we will cherish most of what we own today even 20 years from now. It is mass-produced, less durable and made from low-grade materials and built to pass.

Art Deco teaches us, our legacy is not in our hands but in those who remember us. Today, we look back at Art Deco not as egalitarian or hopeful but as opulent and lavish. The intellectuals of that age openly lived torn by their excesses, some even dying by suicide. Yet it was meant to be designed for the ordinary person and to elevate all. By simplifying design to its essence, it was supposed to democratise design.

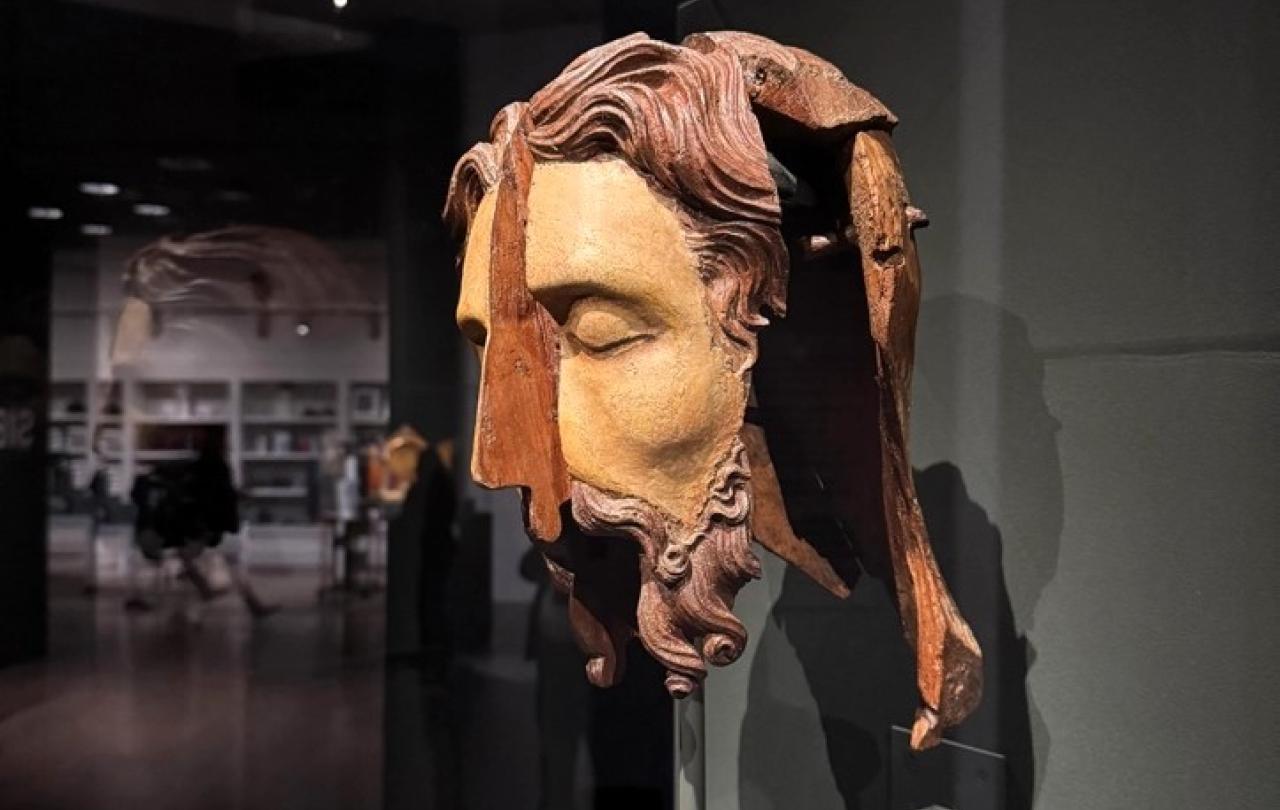

From Wall Street Deco to the frivolous woos and woes of Wodehousian characters and music in the keys of Jazz, this era has made its distinguished, enduring mark on the arts. Beneath the sparkle, what has developed an enduring patina with age, is the high quality of craftsmanship across all fields.

Looking beyond the arts, the Lost Generation has taught us that escapism is elusive and to be cautious but not charmed by machines. We can delight in excellent craftsmanship and cherish the beauty of essence.

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief