In the summer of 1288, outside the city of Bordeaux in Gascony, a small group of travellers approached the city walls. The inhabitants of the city gathered, curious to meet this collection of strange looking clergymen who were clearly far from home. The strangers told them that they had come from ‘over the eastern sea’ with letters and gifts from the ‘Mongol kings’ and the Patriarch in the east. Such strange reports, from visitors emerging from the unseen world over the horizon, a world known only from fantastical stories, deserved the immediate attention of the king.

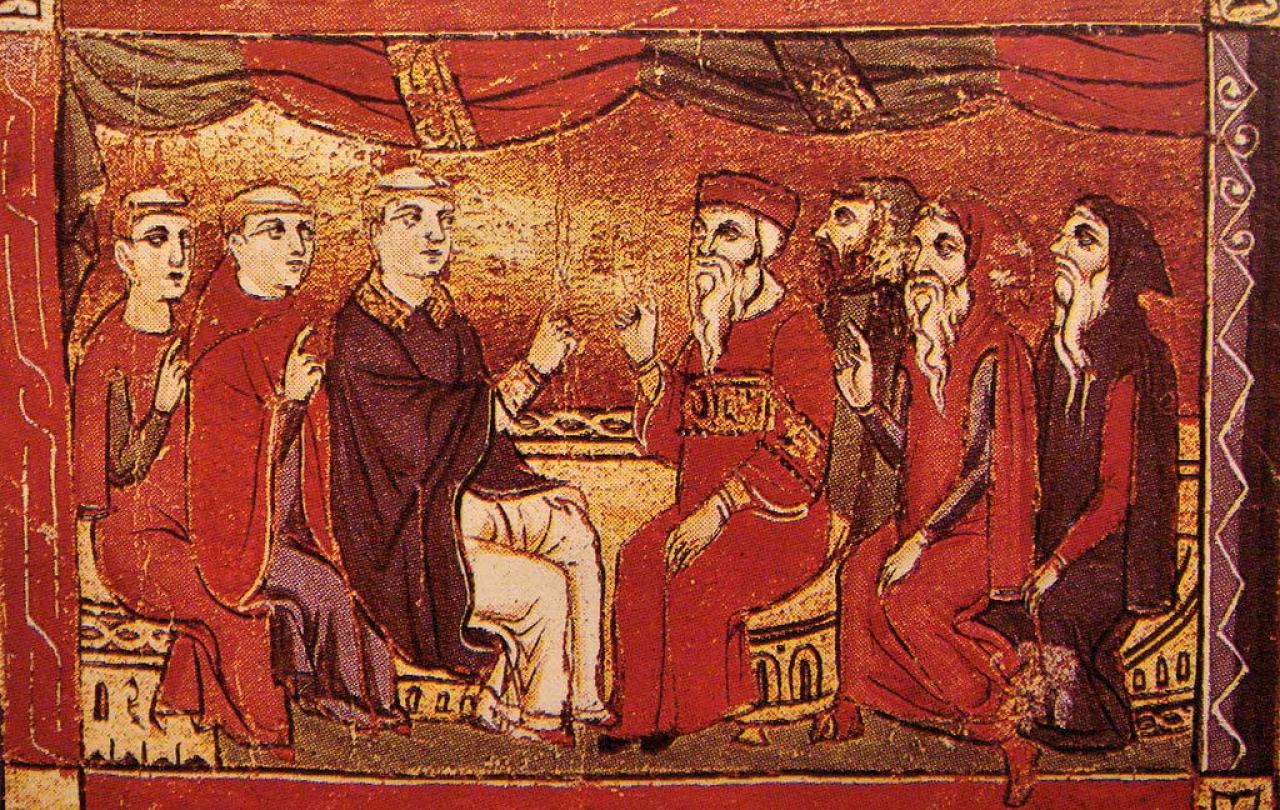

Edward I, the Duke of Gascony and King of England had been resident in Bordeaux for the last two years, overseeing the affairs of his duchy. Assembling his court, he welcomed these visitors from the east. The leader of the travellers was a monk named Rabban Sawma. He was a Uyghur Turk from China. He presented to Edward letters and gifts from the Mongol ruler of Persia, the ilkhan, Arghun, a great-great-grandson of Genghis Khan, and from the patriarch, Mar Yahbalaha, the head of the Church of the East.

As a young lord, Edward had taken the crusader’s oath to go and fight to attempt to regain Jerusalem for Latin Christendom from the rule of unbelievers. Jerusalem had fallen from crusader control in 1244 after the city had been sacked by a large force of Kipchak warriors, nomads from the Central Asian steppes who had been displaced by the expanding Mongol empire. Arriving in 1271, Lord Edward managed to break the siege of the port-city of Acre, one of the last cities held by the King of Jerusalem. Over the next two years, however, his small force accomplished little, mostly skirmishing with herdsmen and burning houses and crops. His time in Acre came ignominiously to an end when he was stabbed with a poisoned dagger by one of his Muslim courtiers leading to lengthy and painful surgery. He left the dream of reaching Jerusalem behind him. Returning from crusade, Lord Edward was greeted with the news of his father Henry III’s death, heralding the start of his own reign. It wasn’t until 1274 that he finally reached England for his coronation. There in Westminster Abbey, he was invested with the splendour of Christian kingship. He swore on the gospel books to uphold and dispense justice and, having been anointed, he was dressed by the bishops in priestly robes and given a sword for the defence of the weak and ‘constraining those who do wrong to the Church’. Now, here in Bordeaux, these new visitors represented something quite outside his experience.

When we dig (literally, archaeologically), we consistently find the evidence of Christian communities that no text ever told us about.

Edward would have been familiar with the stories of Prester John. Reports of a grand and mysterious figure, a Christian ruler somewhere in the east who was both a priest and king, had begun circulating in the mid-twelfth century and were still current in European imaginations, especially as they tried to make sense of the new world that was opening up to them through contact with the Mongols. While there was not really any great Christian king in the Mongol empire, this legend does reflect the (correct) sense of medieval Europeans that a whole world of Christianity was going on beyond their horizon.

Many historians today believe that until perhaps as late as the fourteenth century there were more Christians outside than inside Europe. Yet, in our books of global church history these believers rarely get more than a slim chapter, unrepresentative of their large share of the historical Christian demographic and experience. Throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages there were significant numbers of Christians across Asia and Africa, in Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt; Syria, Mesopotamia and Persia; India, Central Asia and China. Christians had been present in China as early as the sixth century, with significant numbers elsewhere much earlier. Meanwhile Egypt and many other areas of the Middle East had predominantly Christian populations until at least the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, which continued to makeup significant minorities into the twentieth century. In the Middle Ages these areas were global centres of population and development. Bordeaux was one of the largest cities in Europe at the time with a population of nearly 30,000 but cities like Alexandria, Baghdad, Merv (in present-day Turkmenistan) and Samarqand (in present-day Uzbekistan) were among the biggest in the world with populations in the hundreds of thousands, far larger than any in Europe. Present in the historical record of all these urban centres were Christian communities. We find them scattered across the textual record, although for many of these regions this record is far patchier than for medieval Europe, but when we dig (literally, archaeologically), we consistently find the evidence of Christian communities that no text ever told us about.

Most Christians throughout history have lived outside Europe and North America, in pluralistic societies, ruled over by and living alongside non-Christians.

By far the largest group of Christians outside Europe was the Church of the East. This church, once termed, inaccurately, Nestorian, was entirely distinct from the Eastern Orthodox churches but had rather grown out of those early churches that had been founded to the east of Judea, outside of the Roman empire in Persian ruled Mesopotamia. They soon rapidly grew to include communities across Asia, from Syria to China, and India to Mongolia. Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic, was the primary language of worship, prayer, and literature in these communities but the gospels, psalms and hymns were often translated into local vernaculars. Growing up outside the Constantinian revolution, which had seen the ushering in of the conception of Christian kingship with the Roman Emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, and never succeeding in converting the Persian Shah or any other significant rulers, these eastern Christians had no experience of existing in a Christian state. Throughout the Church of the East, Christians always lived in pluralistic societies. The patriarch, the head of the church, was indeed for most of the Middle Ages based in Baghdad, also the seat of the Muslim Caliph, from where he oversaw the affairs of more communities than the Pope in Rome.

By the time that Rabban Sawma made his journey to Europe, there were Christians throughout the Mongol empire (the largest empire until then ever seen). These included many Mongol queens, Khatuns, such as Sorqaqtani Beki, the mother of Kublai Khan, as well as many ordinary Mongols. Christianity had been present in Mongolia for at least a century by the rise of Genghis Khan in the early-thirteenth century and was very popular among many of the tribes he subordinated.

Christianity for well over the first two thirds of its existence then was not a majority European faith and today it is again not majority western. Most Christians throughout history have lived outside Europe and North America, in pluralistic societies, ruled over by and living alongside non-Christians. The western experience is not just unrepresentative of Christianity today but unrepresentative of Christianity in the past. Christendom has been only a small part of the Christian experience.

There in Bordeaux, near where the Garonne flows into the Atlantic, the king of England knelt as the monk who had grown up not far from the banks of the Yellow River began singing in Syriac.

This was the experience of the monk who stood before Edward I. Rabban Sawma had grown up near Khanbaliq, ‘the city of the khan’ (present day Beijing). When still in his early twenties, out of ‘the love of his Lord’ he had become a hermit, living in a cave near a mountain spring, in the manner of many Chinese Taoist, Buddhist, poet and artist ascetics. People would regularly make the day’s journey from the city to come to hear him preach. He was later joined in his secluded life by another young man with a desire to lead a life for Christ named Mark. The two had lived together for some time when one day Mark shared with the older hermit his desire to visit Jerusalem. Together they set out on the long and perilous journey to see Jerusalem and all the sites of the life of Jesus. Like a reverse Marco Polo they travelled west across the Mongol Empire, sometime in the early 1270s, perhaps indeed at the same time as Marco Polo, taking the opportunity for long distance travel which the continent-spanning Mongol empire had made possible.

When the two monks eventually reached Iraq they were told that fighting between the Mongols and the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt, who then controlled Jerusalem, had made travelling the final part of the journey impossible. So they settled down in Iraq until the time might come when it would be safe to make the journey. Such a time never came but while they were in Iraq they became involved in the life of the church and when in 1281 the patriarch died it was with some surprise that Sawma’s young companion Mark found himself chosen by the bishops to be the new patriarch. He chose the new name Yahbalaha.[3] He was the first believer from the more eastern regions of the church to be chosen as patriarch, reflecting the greater involvement such believers were able to have in the life of the whole church under the Mongols. In 1287 the Mongol ilkhan Arghun, seeking to use the European desire to regain Jerusalem to coordinate attacks against his enemy in Egypt, asked Yahbalaha to provide a Christian messenger to go to Europe with gifts and letters for its Christian kings. Yahbalaha recommended his mentor Sawma, also providing him with his own letters of friendship for the Europeans.

A year later, having visited the cardinals in Rome, who had quizzed him on his beliefs and been left perfectly satisfied that he shared the same beliefs as them, and in Paris the King of France, who had shown him around the rapidly expanding city with its sprawling universities, Sawma met the king of ‘Inglatar’. In their audience Edward’s attention was particularly caught by the reference in the ilkhan’s letter to Jerusalem, having again taken the crusading oath only the spring before. But Sawma was far more interested in using his trip to see artefacts associated with characters from the gospels, to hear stories of heroes of humility and of the miracles God had worked in the lives of saints, and to observe the novelty of life in a predominantly Christian society.

In the evening Sawma was invited to lead the king in worship. There in Bordeaux, near where the Garonne flows into the Atlantic, the king of England knelt as the monk who had grown up not far from the banks of the Yellow River began singing in Syriac:

‘Teshbuhta l-alaha ba-mrawme’ ‘Glory to God in the highest…’

On the altar Sawma broke the bread and made the sign of the cross over the chalice of wine. As he broke up the bread he sang: ‘Abun d-ba-shmaya’ ‘Our father in heaven…’ Edward and some of his courtiers and clerics might have recognised the prayer and tried to repeat the strange words or to follow along reciting in Latin. The king and his courtiers approached and Sawma served them. The king of England and the Chinese monk together participating in the divine mystery of Christ’s incarnation and sacrifice.

Further reading and notes

For the text of Rabban Sawma’s journey to Europe:

Borbone, Pier Giorgio. History of Mar Yahballaha and Rabban Sauma (Hamburg: tredition, 2021).

Rabban means ‘our master or teacher’, a term related to Rabbi which was an honorific used for monks. Ṣāwmā means ‘fast’ and is a shortened version of the name Bar Ṣāwmā, meaning ‘son of the fast’, often given to a greatly longed for child, as was the case with Rabban Sawma.

Mar meaning ‘Lord’ was a term of respect applied in the Church of the East to senior clerics and saints.

Yahbalaha means ‘God has given’, with ‘alaha’ being the word always used in Syriac for God. As with Sawma it is a name given by parents in thankfulness for the child. Mark chose it as a name borne by two previous patriarchs, perhaps recognising his appointment as a gift from God.