“The bridge from chaos to hope.” This was the rather grandiose language used on social media platform X last summer by one prolific tweeter boasting 4.4 million followers. What they were describing, however, was not a religion or philosophy, nor a social movement or political party, nor a breakthrough in medical technology or a self-help technique. Rather, financier Michael Saylor was talking about the world's biggest cryptocurrency, bitcoin.

Saylor’s profile on X declares that “#Bitcoin is hope.com”. That website contains, among other things, video clips of Saylor talking about how “bitcoin is the manifest destiny for the United States of America”, “bitcoin is economic immortality”, “bitcoin is forever money” and so forth.

Saylor is in fact just one - albeit a particularly successful one (his net wealth stands at around $10 billion, according to Forbes) - of a number of vocal crypto advocates, trying to explain the huge, transformational impact on society that the cryptocurrency will supposedly have. Their precise arguments can vary, but are often along the following lines: the fiat money system is broken due to manipulation by governments and central banks - for instance through money printing - leaving control of the money supply in the hands of a small group of the rich, while the purchasing power of the general public is eroded; in contrast, bitcoin is incorruptible, not controlled by the government, available to everyone and finite in supply.

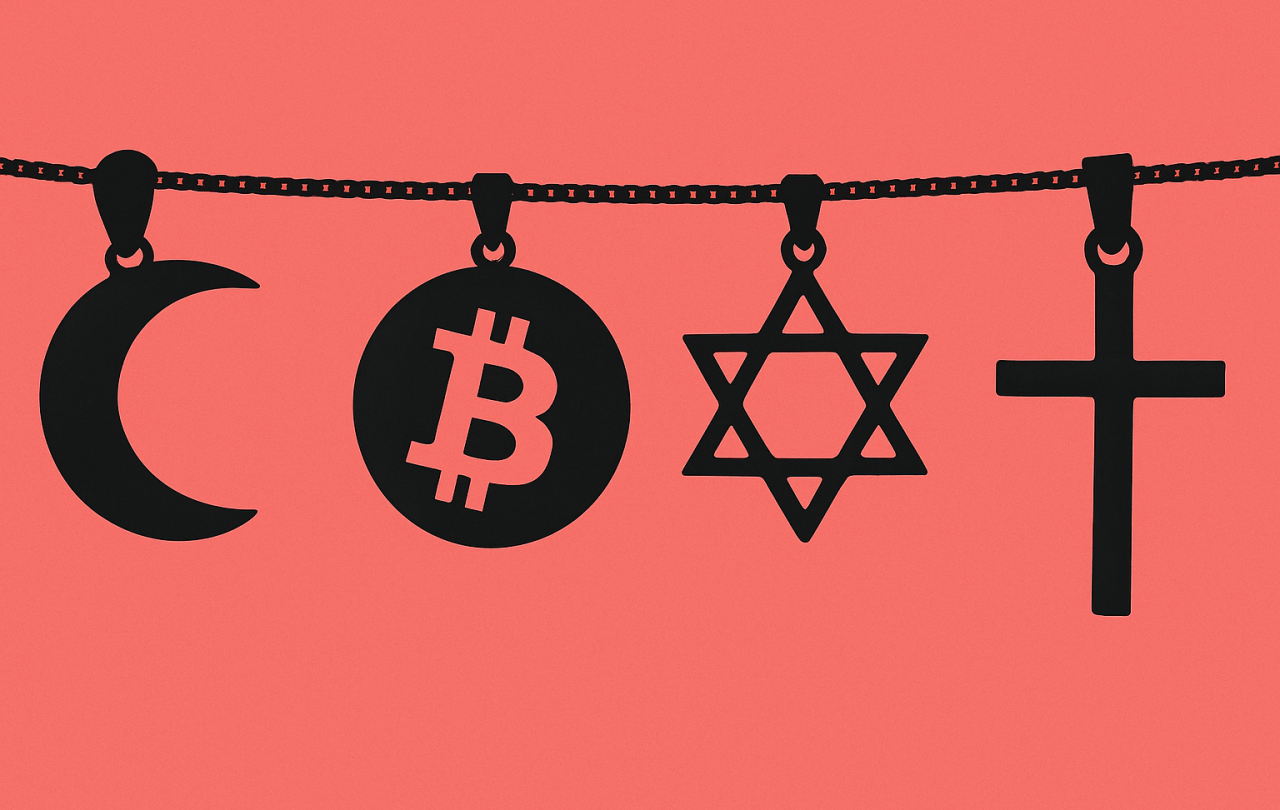

A common thread running through some of the writings and talks of a number of these bitcoin enthusiasts is a quasi-religious language, used to convey bitcoin’s importance.

Hope.com, for instance, includes a research paper on “The bitcoin reformation”. Its author writes: “It wasn’t until I studied the era around the Protestant Reformation that I felt I’d found a potential blueprint of sufficient scope” to describe what is happening with bitcoin.

Particularly vocal crypto proponents are known as bitcoin evangelists, while some crypto investors will talk of fellow “bitcoin believers”. They can even drink their coffee from a ‘bitcoin salvation’ mug) (which depicts two winged cherubs holding the cryptocurrency). Non-believing sceptics are termed “no-coiners”.

Early bitcoin adopter Roger Ver - who has been indicted on fraud and tax charges, which he says are false - is known by the nickname “bitcoin Jesus”. One non-profit decentralised community is named Bitcoin God.

The precise mix of irony and sincerity being used in such examples is of course debatable and will vary. Nevertheless, among the most fervent crypto investors there appears to be an earnest belief in the transforming power of bitcoin.

But there may be additional reasons why some of the most fervent proponents instinctively reach for such language.

“There’s a link with forms of transhumanism - the idea that we’re in the middle of an upgrade of humanity.”

Dr Roger Bretherton, a clinical psychologist and Seen & Unseen contributor, argues there are elements of tribalism and “the psychology of identity” in some of the most cultic aspects of the crypto world. He sees some similarities there with “old 60s cults of people believing UFOs were going to land in their backyard”, talking about crypto as a cult rather than crypto as a currency.

“People overlap their identity [with a particular movement]. They're saying ‘that's me, that's who I am,’” he said.

“In periods of uncertainty we seek to find certainty in our groups. We're in an individualistic society.”

Use of religious language also points to a belief that bitcoin/crypto/blockchain will bring about some form of a radical global change less on the scale of an incremental technological development, and more akin to a transformational religious experience.

“There's an element of faith and an eschatology attached to crypto: 'this is the new thing that will change the world,'” said Bretherton.

“There’s a link with forms of transhumanism - the idea that we’re in the middle of an upgrade of humanity - the kingdom of tech is coming. It feels like crypto becomes part of the same narrative. The key question is whether our future lies in technology and power, or in love.”

For such fervent bitcoin proponents, attempts to rubbish their beliefs are often futile. Indeed, trying to do so may only serve to strengthen the believer’s resolve that they are right.

“There's a cognitive dissonance,” said Bretherton. “The more ridicule you've had to go through, the more you've given up, the more social difficulty you've gone through - particularly if you've given up a career to pursue crypto - then the stronger your belief. It's the sunk cost fallacy.”

So far, bitcoin believers have proved the doubters wrong. The price of the coin has gone from less than $20,000 in the wake of the collapse of crypto exchange FTX in late 2022 to around $118,000 at the time of writing. Saylor has turned MicroStrategy (now known as Strategy) - the company of which he was CEO in 2020 when he decided to use it to buy and hoard bitcoin - into a $110bn market cap firm that has spawned many copycats.

But what importance bitcoin eventually assumes in society is still very much an open question. It has not yet become a form of payment for our morning coffee or for buying a house, and maybe it never will. Whether it can really function as “digital gold”, a hedge against inflation or “a bank in cyberspace” (as Saylor calls it) is debatable. But it has already made huge strides, soaring to a market price well above what most people would ever have imagined. In July, US Congress passed a landmark bill regulating stablecoins - a type of cryptocurrency pegged typically to the dollar - in what is being seen as a huge step forward for the industry.

Nevertheless, it seems likely that some of the wilder claims made about bitcoin may not come to pass. What happens if true believers are left disappointed?

Bretherton says such belief systems have to subtly change their “metanarrative” as and when they do not deliver on initial promises.

“It can't make predictions that can be shown to be false,” he said. “If crypto doesn't deliver its promises in the future, it has to find another way that's softer but which lasts. So it either collapses or it finds a way to become more nuanced."

Whatever importance bitcoin eventually assumes in society, our desire to put our faith in it - or in anything else - reveals something deeper about our human nature.

In the Bible, the book of Ecclesiastes explores humankind’s attempts to find meaning in human lives without God. The main character tries career, pleasure and wealth. But ultimately, they find that these things are just “meaningless”, “vapour” or “chasing after the wind”.

That search for meaning, for the eternal, is inbuilt in our character. As the book’s author puts it: God has “set eternity in the human heart”.

We are not designed merely to be born, to live and then to die. Instead, each one of us has been created with an inherent desire to know if there is something eternal out there, and to find out whether we can be part of that story. Crypto cannot offer us that salvation. The only thing or person who can, the author of Ecclesiastes would argue, is the One who put that desire in us in the first place.

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief