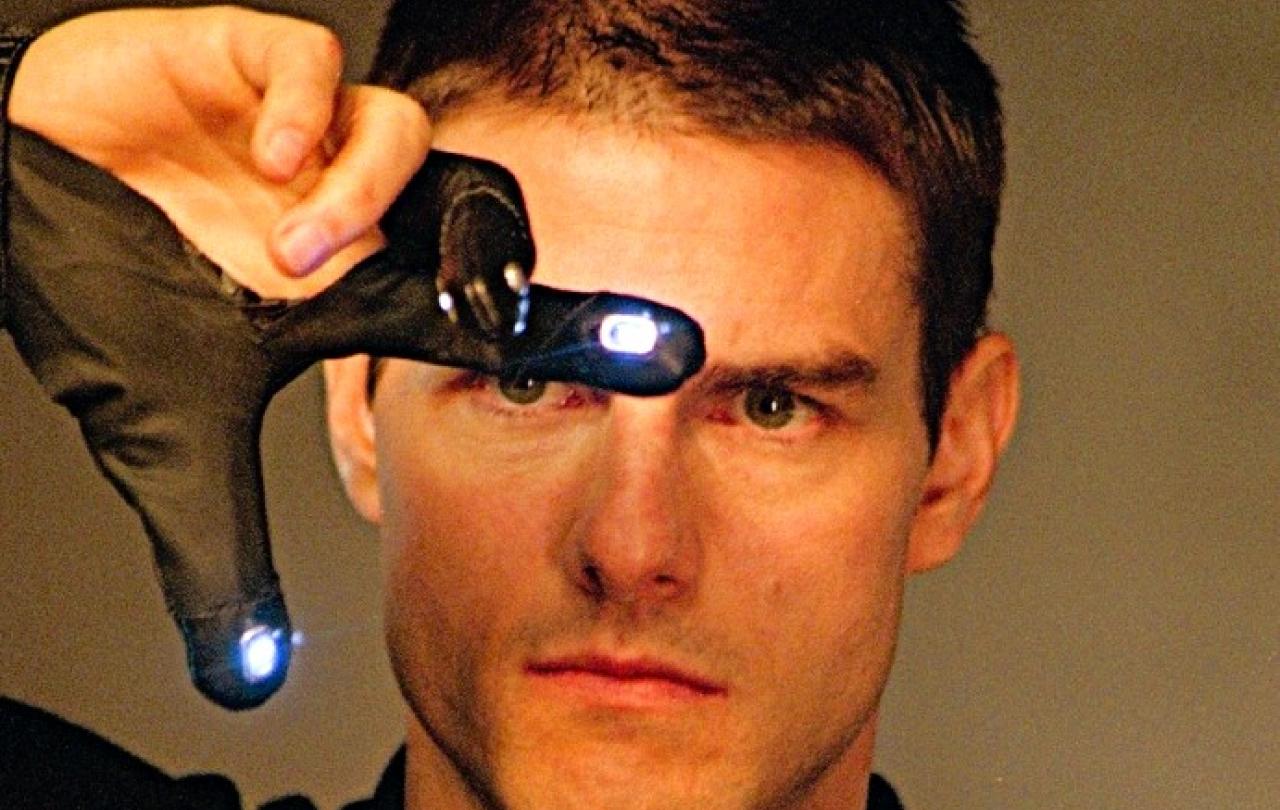

The go-to for any news item about using AI to predict crimes before they happen is Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report from 2002, starring Tom Cruise as a futuristic cop, who employs human “precogs” as clairvoyants to get ahead of the villains.

So, I’m far from the first to name-check it as showing the dystopian future that the UK’s Ministry of Justice heralds with its test project to “explore alternative and innovative data science techniques to risk assessment of homicide.”

That use of “homicide”, rather than the more British “murder”, is telling, almost like the Ministry wonks have just watched the movie. The pressure group Statewatch has no doubt where they’re heading, with data being used on people who may never have been convicted of an offence and “will code in bias towards racialised and low-income communities.”

Spielberg was always ahead of the curve. But my fear is less the chilling dystopia that Statewatch sees in its precog. Actually, I’m more worried about the past in this context, or rather in how we treat the past.

If I haven’t to date done anything wrong, then I have committed no offence. I am literally innocent. And that’s an absolute. An interpretation of data that indicates that I’m more likely to commit a crime than others is neither here (in my conscience) nor there (in the judicial system).

Furthermore, there’s a theological point. If it is so, as we’re told, that no one is without sin, then we’re all culpable in the pasts that we have lived so far, but the future contains all we have to play for.

To suggest that some of us are more likely to screw up in that future than others is very dangerously deterministic. It’s redolent of Calvinism’s doctrine of the “elect”, those who have already been marked for salvation and eternal bliss, regardless of what they do or don’t do in this life, while the rest of us, however virtuous our mortal deeds might be, will rot in hell.

Neither Calvin’s determinism nor the Ministry of Justice’s prejudicial database leave any room for redemption. They’re just trying to identify events that will definitely (the former) or are likely to (the latter) happen. Conversely, we live in hope (for some of us a sure and certain hope) of a future in which we can be redeemed, whatever we have done in the past.

And that’s why I find Minority Report an unsatisfactory analogy for the development of real-life precrime technology. It is a film that is only about determinism, which leaves no room for either free-will or redemption. And that’s applying a form of intelligence that is truly, er, artificial.

The vital thing is that hope is fulfilled, the prisoners make it to their paradise after worthless lives spent in jail. Justice is seen to be done.

A more helpful movie, richer in its development of these themes – and not just because it’s got the word that I favour in its title - is 1994’s The Shawshank Redemption, based on a novel by Stephen King. Here we have the idea explored that the past isn’t only irrelevant to our futures, but doesn’t even really exist in time in relation to the future.

It’s bursting with more religious themes even than Clint Eastwood’s spaghetti westerns, which are really only the righteous saviour turning up to defend flawed goodies from evil baddies, again and again. For a start, The Shawshank Redemption is set in a prison, where whole lives are spent atoning for crimes that have or haven’t been committed. See?

Lifers who are released after decades struggle to cope or kill themselves. The central character, a messianic figure, lives in hope with his convict friend of reaching a beach in the Virgin Islands, while the prison warden describes himself as “the light of the world”, but is assisted by his prisoners in money-laundering – washing clean – his ill-gotten gains.

I could go on. But the vital thing is that hope is fulfilled, the prisoners make it to their paradise after worthless lives spent in jail. Justice is seen to be done. But the important thing here is that there is no pre-crime determinism. The future, which often looks hopeless, is rolling out towards the possibility of redemption, which ultimately becomes the only certain reality.

One can dwell on movie plots too long. They are only, if you’ll excuse the pun, projections of life. But it is nonetheless irritating both that a government department with Justice in its title can believe it worthwhile to explore how it might deploy AI to predict who tomorrow’s criminals are likely to be and its critics condemn it by using the wrong dramatic analogies.

Minority Report was a dystopian thriller that suggests that the future can only be changed by human intervention. The Shawshank Redemption showed us that inextinguishable human hope is in a future we can’t control, but can depend on.

Anyone who is interested in justice, especially those who work in a ministry for it, might benefit from downloading it.

Celebrate our 2nd birthday!

Since March 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free. This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief