Suffolk-Essex musician, Rev Simpkins, creates music of great imagination and charm, inspired by the history and geography of East Anglia.

The Reverend Matt Simpkins is the fourth generation of his family to be ordained priest in the Church of England. Prior to ordination, he was a professional musician having been a choral scholar at Oxford University and a Lecturer in Music. He came to musical notoriety through raucous exploits in Fuzzface, Gospel-fiddle duo Sons of Joy, and as a solo artist performing as Rev Simpkins & the Phantom Notes. He collaborated with Kenney Jones of the Small Faces to reconstruct the orchestral parts of their 1968 psychedelic masterpiece Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake.

Working as a parish priest a few miles away, Matt came to the saltings to retreat and compose compelling and compassionate songs about his community’s real-life experiences during the pandemic.

In 2019 a diagnosis of cancer brought an opportunity to make new music and he released the hope-filled album Big Sea in 2020. Written around his initial time of illness, the album is an exuberant celebration of the peaks and troughs of life and death through off-kilter songs about east coast creeks, shattering storms, mystic pelicans and the Colchester martyrs. Shades of Captain Beefheart, Pavement, and the Kinks meld with Evensong choirs and pipe organs, pre-war Gospel Blues, string orchestras, brass bands, and Bert Jansch style fingerpicking.

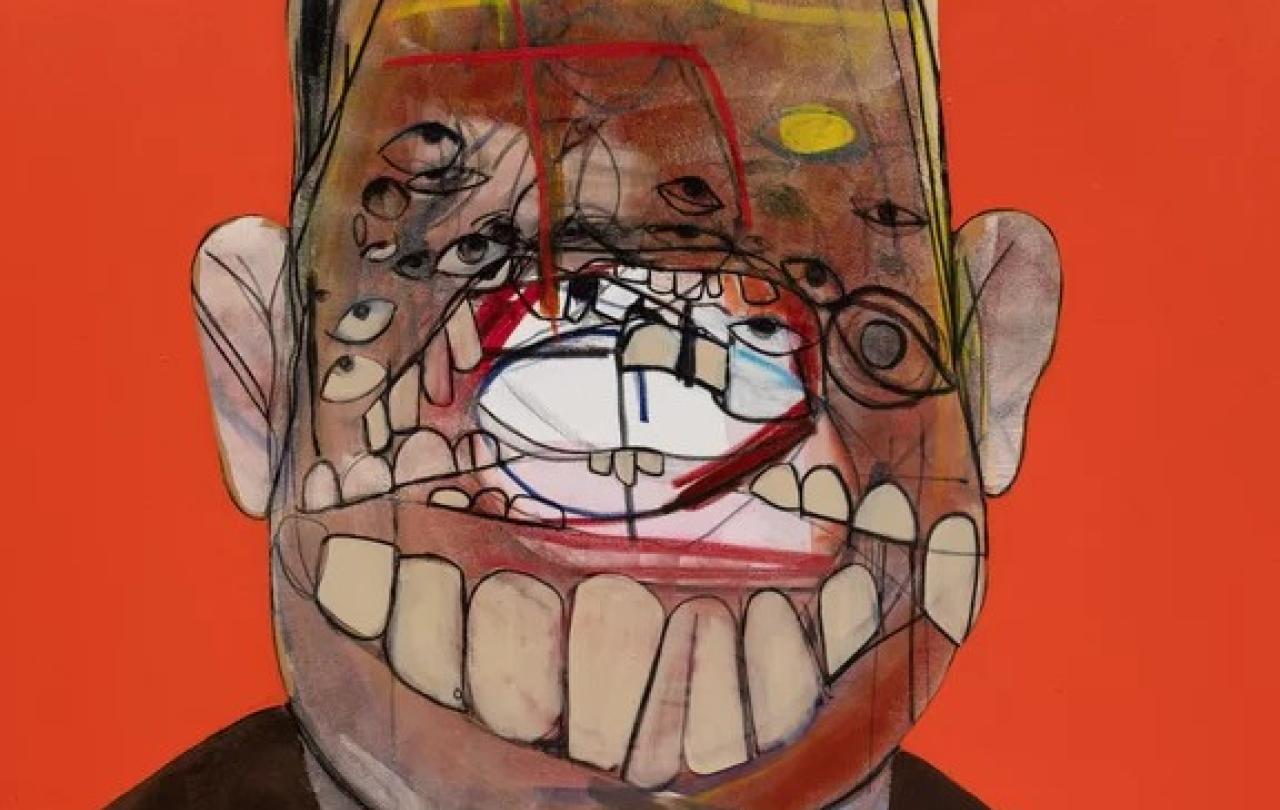

Saltings, his acclaimed fourth album and book, was created with the illustrator, Tom Knight, and is a loving portrait of the mystery and beauty of Essex's salt marsh wilderness, and a meditation on the real human cost of the wilderness time of the pandemic. Found within 50 miles of London, the saltings are one of England’s last natural wild spaces. Working as a parish priest a few miles away, Matt came to the saltings to retreat and compose compelling and compassionate songs about his community’s real-life experiences during the pandemic. Saltings portrays hope found amid wilderness. On this album he mixes the colourful folk tradition of Appalachians Mountains with the melodiousness and carefully-observed lyrics of the Kinks. Close harmonies intertwine with banjo, French horn, and bass.

“Zany in parts, moving in others, you’ll be hard pressed to find a more unusual, inspired and profound album this year.”

His most recent album and band, Pissabed Prophet, was born in the resonance field of an MRI machine, as he tried to keep himself sane by mentally harmonising over the deafening noise of a medical scanner. Excited by the potential of the sounds, he recruited Dingus Khan and SuperGlu frontman Ben Brown to help him turn these ideas into an EP. Working over the summer of 2022, the pair formed an immediate intense friendship and working relationship, and ideas for the EP quickly blossomed into an album’s worth of material, overspilling with joyous and ruminative songs, born of an emotionally turbulent time in which Matt underwent unsuccessful immunotherapy for stage 4 cancer. I have previously written that being, “Zany in parts, moving in others, you’ll be hard pressed to find a more unusual, inspired and profound album this year.”

We meet at Colchester Arts Centre – which self-describes as the little church with the big attitude deep in the heart of Essex - in a room that was once the vestry for St Mary at the Walls Church, now deconsecrated.

JE: Music and faith seem to have been combined in your upbringing. Can you tell us how that came about and its influence on what you now do?

MS: Music and faith have been total influences. I am the son, grandson and nephew of Anglican clerics. While I was in my mother’s womb, headphones were placed on the bump and I was played a mix of Boney M (‘Rivers of Babylon’) and Vaughn Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis. My parents let me bash at their piano from a very young age. I was allowed to experiment before begging for piano lessons. I sang in church choirs and played the violin for Morris dancers. I was a church organist and played in bands.

JE: You embraced a range of different styles early on - from choral to rock - with each influencing the other to create your eclectic and distinctive styles. What is it that interests you about crossing boundaries and blending different styles in this way?

MS: Growing up I didn’t realise there were distinctions and just played whatever there was. I had a delight and fascination with different sorts of music and began to realise that the fundamentals go across all types of music, so that aspects of ‘Penny Lane’ relate to elements of Palestrina and Tallis. Music moves me and, once I understand its working, I can experiment and play with those things. The way I write is similar to writing classical music through the use of counterpoint and harmonic tricks. If you want a dividing line, you have to force it on the music. I’m not interested in dividing lines between music or grace.

Music is just such a brilliant expression of our humanity and my faith is that all these things have something to do with grace. Christianity is music: the Psalms are the bedrock of Christian faith and worship. All is melded into one. I’m obsessed with the Psalms and the violent mood swings they contain. Their emotional honesty intertwines music and human life with grace. The richness of creation and human experience – for good and ill – mean that I’m not willing to believe that parts of that are somehow untouched by grace and redemption – even our own suffering and sorrow.

JE: Your work contains a rich vein of humour. What is it about the comedic that meshes with your wider vision?

MS: At the core of creativity is playfulness. Without playfulness there isn’t seriousness. There is great joy in the creative process and playfulness when recording. Now, I often play together with my son. I’m also thick as thieves with Ben Brown. In the studio we just bounce off each other and egg each other on in adding counterpoint and harmonies. Compositional play is all the way through the creative process and we are playing with sound in the recordings. Forming and shaping songs to sing about real life, brings comfort.

JE: What impact have the challenges of illness, both personal and social (through the pandemic) had on your work?

MS: I came back to music because I got ill. After ordination I thought that music was something that formed me but was not part of my ministry. When I first got ill, I found it hard to pray, so I read those ancient songs - the Psalms - as I always have. I became especially interested in the bits people often leave out. We need to see the difficulties that underly the songs but also see the joy like the Psalmist. This is the darkness of grace. Shit happens but grace remains.

We know that Jesus prayed the Psalms and believe that he takes all human experience up on himself on the cross. So, if I’m having a scary experience like an MRI scan why not think what I might do creatively with that shuddering racket in a song? I take up my experiences in the faith that they have some connection to grace. Human experience and shared experience can result in emotionally dynamic and authentic songs.

Saltings, I wrote on my own because of lockdown. The songs all came quickly, partly as a coping mechanism in a pressure-cooker environment.

JE: Your recent albums, though addressing and confronting significant personal and social challenges have remained resolutely positive, upbeat, engaged and wondering. What are the wellspring for these strands in your music?

MS: I’m trying to give an authentic sense of joy in my music. I find that joy in making music with people I love. We just get together and make music. They know it’s authentic. It’s fun, really fun, and has been incredibly therapeutic. Music is bound up with identity and community and reconnecting with music has been good for my faith. Light and gathering together are part of the Holy Spirit’s personality.

JE: Your work draws significantly on your locality and its heritage. Why has it been important for you to have that local grounding and inspiration?

MS: You write about what you know and use music to come close to place. In writing Saltings I was walking over the marshes praying and pondering the amazing history of this area; Eastern England’s connection to the continent and with radical faith and politics. You can’t capture the saltings in photographs, they are Southern England’s last wilderness. Colchester, where we are talking, has also always fascinated me. We are literally sitting on top of amazing remains, a real richness. These places can come alive in music.

JE: Through music you explore faith in everyday life and as a performer you are on a mainstream label and perform primarily outside of church. Why are these things important to you and what sort of reaction do you get to them?

MS: The musicians with which I play are seriously good musicians – intelligent and sensitive. Only a few of them are Christians. We have shared experiences, although I expect faith may not cross their minds. They enjoy playing the music. However, people often ask about faith at gigs or in interviews. These are wonderful ways to bring faith into areas where it might not otherwise be. The venues I often play in have histories of community or religious use, as is the case with this Arts Centre where we are meeting today.

I want to make music on a label that has all sorts of bands on it because I want to be in the world as a Christian. I don’t like gatherings where I am squirrelled away with people who think the same as me. Not much of the Bible is about being with those who are the same as you.

I played a Sons of Joy concert – two screeching fiddles playing Gospel and chants – on a lightship and, after the concert, was approached by the owner of Antigen Records. I went back to the label several years after ordination with the recordings that became Big Sea and was very nervous about doing so, but they were very keen. Antigen is a label that has encouraged characterful, inventive music and which is not interested in barriers. There is not a dud release on that label!

I consider myself to be a thoroughly Anglican Anglican. William Temple, John Donne, George Herbert, as with the Wesley’s, formed me. Temple’s Christian Life and Faith says that where there’s true community, that’s where the Holy Spirit is.

“If you find something…that promotes true fellowship, there you know the Holy Spirit is at work...It may be that those with whom you join are not themselves Christian…Never mind that.”.

Augustine teaches us not to pretend we can know where the boundaries of the City of God sit, as we won’t know where they lie until the End Times. What is the Church for, if we can’t engage with humanity as it is? Part of priestly ministry is to recognise that there are gifts in every person (in and out of church) and to be open to grace, even (or perhaps especially!) when you don’t expect it.

https://revsimpkins.com/ and https://antigenrecords.com/artists/pissabed-prophet/

A new Pissabed Prophet EP entitled Apple is out in November on Antigen Records.