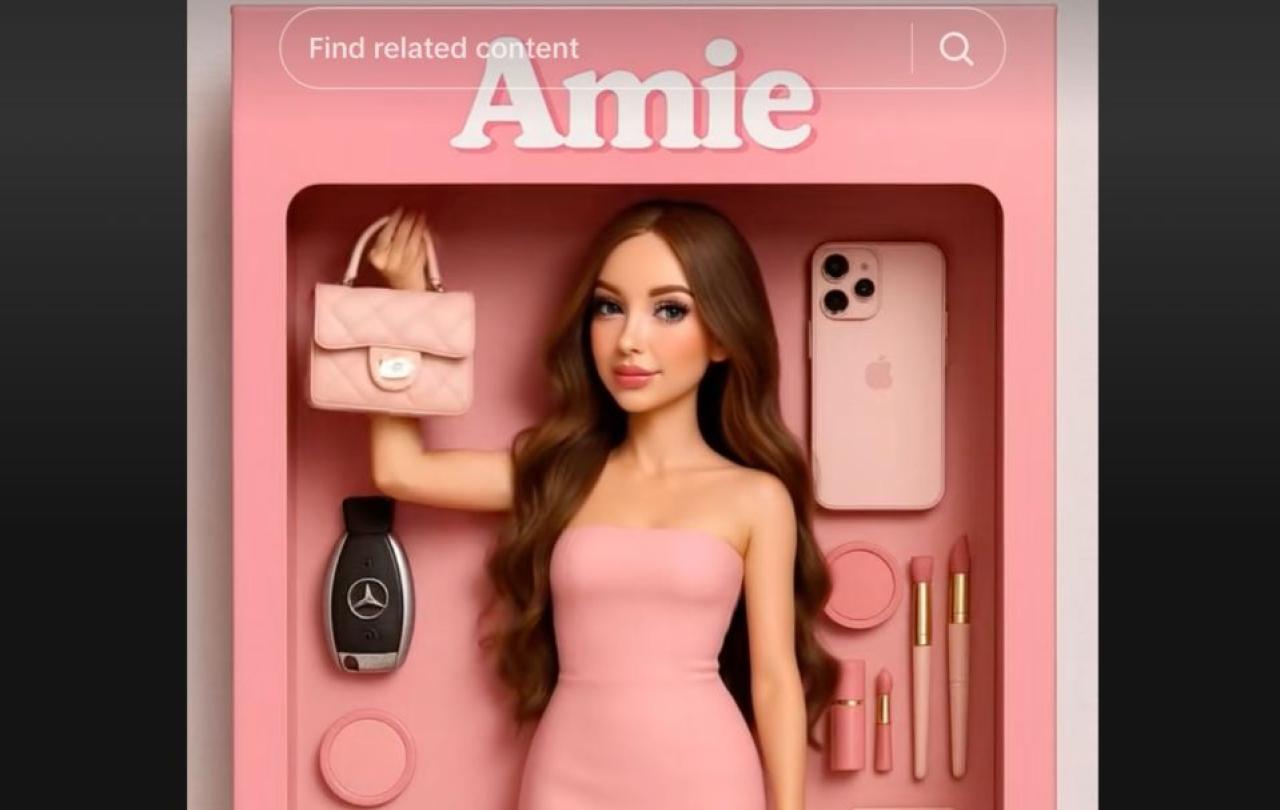

If you spend any time on any social media platform you would have probably seen the ChatGPT Barbie trend. Resembling packaged toys, the AI depicts you like a doll or action figure. At first, I thought I was only seeing it because of the LinkedIn algorithm. But then I started to see articles in my feed from mainstream media outlets teaching people how to do it.

Generally, speaking, I am not a trend follower. I am one of those annoying people who doesn’t get involved with what everyone is doing just because everyone is doing it. Thankfully, I don’t suffer from FOMO (the Fear Of Missing Out) and I don’t think I am swayed much by peer pressure. But I like to stay informed about what is going on. So I can have something to talk about when I meet people in new settings and to remain relevant. So, when this started popping up in my feeds, I investigated it, and I was pleasantly surprised.

I am not anti-AI. I have embraced and seen the benefits of AI in my own life (this sounds a bit weird, but I think you get my point). I understand and accept that it will, can and has improved productivity and creativity. I use ChatGPT all the time for social media content and captions, brainstorming, titles for articles, coding problems, research and language translations.

But like many, I have long been sceptical about the growth of AI use and the viability of its long-term sustainability. I wouldn’t describe myself as a climate warrior, but I do believe that we have a responsibility to ourselves and the generations after us to use the finite resources of the planet frugally. The AI-powered Barbie trend throws that out of the window.

The current Trump administration has facilitated a shift away from ESG (environmental, social and governance) targets in the world of business. For the most part, the criticism of this in the media (social and mainstream) has been focused on DEI targets. But perhaps, in the face of slow economic growth and because this began before the Trump administration took office, the move away from environmental targets or what I would call environmental stewardship, or frugality has received limited coverage.

I have never understood why proponents of the climate emergency, have made themselves bedfellows and in some cases, wholehearted supporters of the AI revolution. A typical data centre uses between 11-19 million litres per day water just to cool its servers, that’s the equivalent of a small town of 30,000-50,000 people. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts by 2030 that there will be a doubling of electricity demand from data centres globally equating to slightly more than the entire electricity consumption of Japan. This growth will be driven by the use of AI in the US, China, and Europe. That’s why vocal support of the climate emergency and advocating escalated transition to AI, as is the position of the UK government, currently seems paradoxical to me.

This isn’t hyperbole, Sam Altman, CEO of Open AI recently tweeted asking folks to reduce their use of the ChatGPT’s image generator because Open AI’s servers were overheating.

That is why I have been pleasantly surprised, by some of coverage on the Barbie trend. Arguments are now being made more loudly about the true cost of unlimited AI expansion.

I am not against progress or AI expansion entirely, and I have some support for the argument that governments have pursued net zero policies at a rate that is impractical, expensive and unviable for the average consumer in Western democracies. However, the Barbie trend reveals our tendency to choose waste and consumption for fleeting pleasure. For many of us, we have probably just thought, ‘It’s just a bit of harmless fun’. But the truth is it isn’t, it’s just that we can’t see the damage we are doing to the environment. That’s without going into the financial and privacy costs associated with the AI revolution. It really is a case of that age old adage, ‘Out of sight, out of mind’.

The challenge is now that we know, what do we do? Do we continue to be part of wasteful AI trends? Or do we use AI to add value, increase productivity and solve problems?

Celebrate our 2nd birthday!

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief