More than two years ago the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan for Nagorno-Karabakh/Artsakh ended, but many fundamental issues remain. Who will provide security and services for the region’s residents - Armenians? How is humanitarian aid managed and by whom?. And, nobody knows if the so-called “ceasefire” will hold.

Azerbaijan won the war, with the Armenian side losing significant territory in and around Nagorno-Karabakh. Over one-third of the population became refugees, losing their homes and everything they managed to create during all their lives. Now Azerbaijan controls those territories, but they mainly remain not inhabited. Those territories that remained under the control of Armenians, are still populated only with Armenians, and Azerbaijanis have to approached them. In order to prevent any armed conflict in the region (in fact, to protect Armenians from Azerbaijanis) 4,000 Russian soldiers-peacekeepers and emergency services staff keep an uneasy peace.

They were already in Artsakh within hours of the peace agreement’s signing. Artsakh is part of Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian enclave within Azerbaijan. Since then, peacekeepers have done a lot: escorting villagers to visit graves, mediating disputes, tending crops, and fixing water pipes. They set up checkpoints along the only road connecting Artsakh to Armenia, to ensure a safe corridor for Armenians living in Artsakh.

Before the war, there were 150 000 Armenians living in Artsakh. After the war, the numbers decreased to 120 000. Some people didn’t come back from Armenia, where they found a shelter, after losing their homes. Some moved to Armenia or Russia because they didn’t want to live in uncertainty. And, unfortunately, wars take lives, and some people lost their lives during that period. But mostly the people of Artsakh remained resilient and wanted to live in their homes or create new ones, even not knowing for how long they will last.

It is said in Artsakh and Armenia, that every human being now living in Artsakh is a hero. They say that because it’s not easy to sleep every night not knowing if you are going to wake up in the morning tothe sounds of bombs, or if you are going to wake up at all. Because since the end of the war Azerbaijan has done so much to traumatize people physically and mentally.

According to the peace agreement Armenians and Azerbaijanis should remain in the positions they were in at that moment. In other words, after the signing and the cease-fire, they have no right to move forward and occupy new territory. However, after just one month, Azerbaijan entered and captured two Armenian villages, taking more than 60 Armenians as prisoners of war. After that, during those two years, similar military operations were repeated numerous times by Azerbaijan. Again, people were afraid of the sounds of war, they heard and saw military drones, and felts those feelings again.

It was also a manifestation of psychological violence that the Facebook page of the Artsakh National Assembly was hacked, with a flag of Azerbaijan posted as the main picture. The accompanying text read:

“We call on the Armenians living in Karabakh to leave the occupied territories of Azerbaijan within 168 hours, otherwise all Armenian citizens will be killed.”

People had no idea if they should believe that threat or not. Maybe this was just another provocation, but could it really happen? Did they need to evacuate everyone. Or not believe it and stay in their houses? No matter how hard people try to stay strong, no one closed their eyes that night, thinking that it was possible that Azerbaijanis will enter the cities and villages and commit a genocide against the peaceful residents.

Many violations happened during these last two years. And then since December 12, 2022, Azerbaijan has blockaded the only road connecting Artsakh to Armenia depriving residents of a basic right - a right of freedom of movement. It’s the only road people can travel in and out on, the only road through which the 120 000 people get food, medical and other supplies. It's the only road that connects Artsakh with the outside world. Blockading this road caused a humanitarian disaster. Lack of food, medicine, work, and cash. Nobody can pass along that road.

The blockade was not enough, and Azerbaijan decided to shut off gas and electricity supplies to Artsakh again during the coldest months of winter. People simply do not have the opportunity to warm up. In a sub-zero temperature, people were deprived of the opportunity to turn on a small heater for hours. The little children, unable to stand the cold, fell ill and ended up in the hospital.

The healthcare system in Artsakh is still a little weak. There are hospitals, but people who are in critical condition, between life and death, are mostly transferred to Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, in order to receive proper treatment there. However, due to the blockade, some people could not be evacuated, and died.

Also, a food rationing system was introduced in Artsakh, where people can get food only with a coupon. According to the system, every person gets one kilogram of rice, one kilogram of pasta, one kilogram of sugar and one kilogram of buckwheat in a month. With those coupons, people come to the stores and buy their share.

Food is so scarce that locals have begun to notice that street animals are starving to death because they can't find food in the dumps. The reason is that people have nothing to throw away.

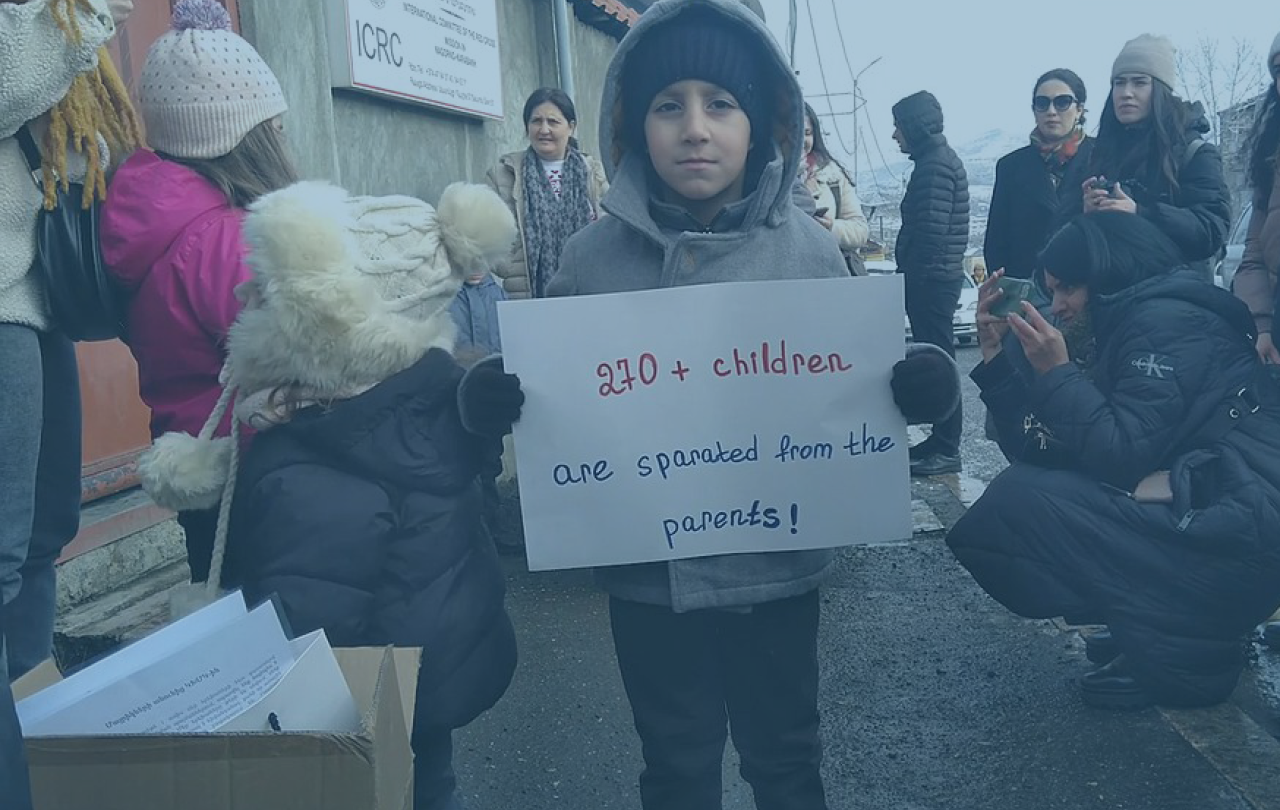

Many families have been divided because one or another family member mistakenly stayed on the other side of the blockade. Many people went to Yerevan to see a doctor and due to the road’s blockade cannot return home. The same impact was felt for those going in the opposite direction. In total, 1,100 people remained in Armenia and did not manage to return to Artsakh.

Artsakh children are deprived of the right to education. Schools and kindergartens are closed for months because there is no way to heat them. Also, they cannot feed children in kindergartens due to the lack of food, and children in schools cannot take food to school, because there is almost no food at home. And sitting for six or seven hours without food is very difficult for children.

Azerbaijanis also regularly cut telephone and Internet wires, and people are deprived of the only opportunity to even connect with the world virtually.

People are trying to overcome all these difficulties, but no one knows when these provocations and torments will end. When they will finally be able to live decently. And the world hasn't even heard of that small area in the far South Caucasus and the resilient people of Artsakh, who are so loyal to their roots and homeland.