Climate change, smartphones, a loss of social cohesion: these are just some of the potential culprits for an oft-discussed, much worried about, anxiety epidemic. But what if our worries can’t be fully explained by any particular feature of the modern age? What if worry is in fact an ancient problem that afflicted the first century no less than the twenty-first? What would that mean for how we should respond?

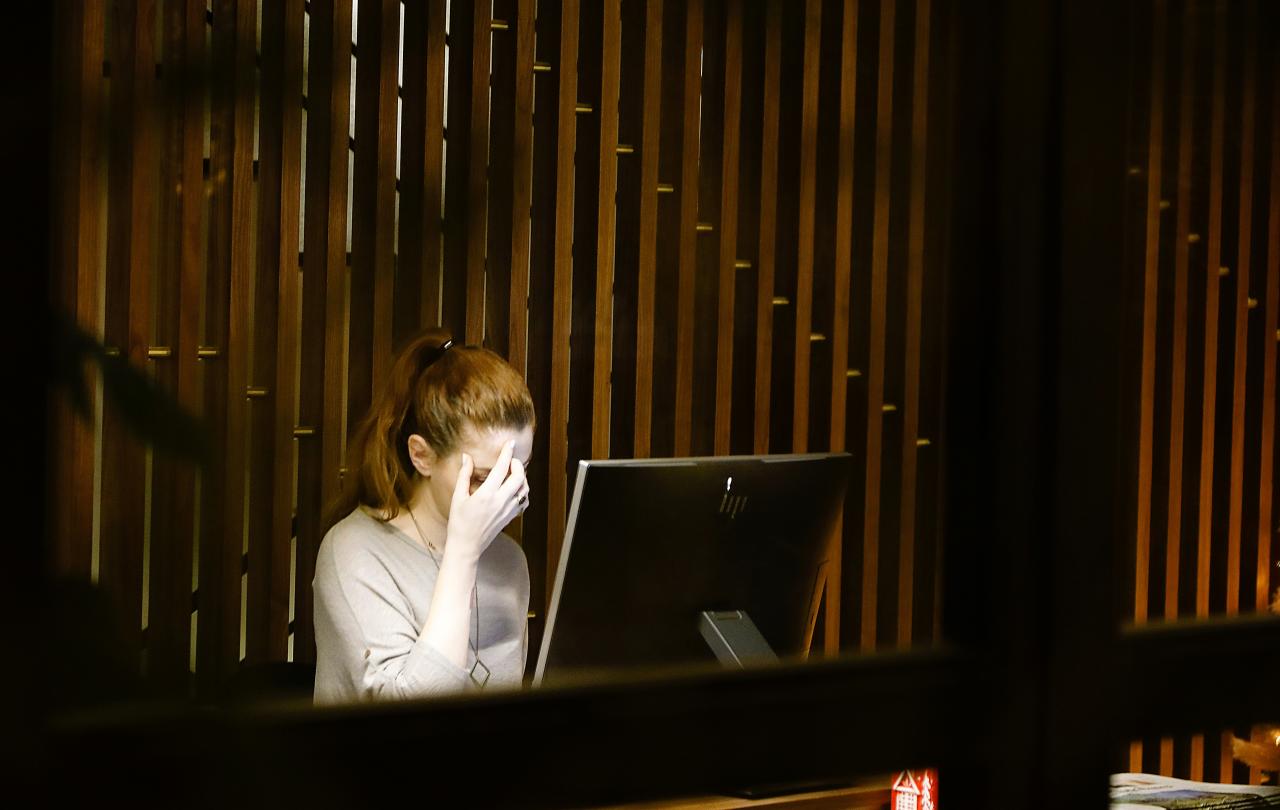

I’m not a psychologist, or a social scientist, but I am a common or garden worrier. And worry worms its way into my life through the gap between responsibility and control.

I first encountered this at work. As someone who organised events, I felt responsible (and would be held responsible) for how many people signed up. But I soon came to the painful realisation that I didn’t control how many people signed up. I had responsibility but not control - and worry wormed its way in through that gap. And that didn’t seem fair to me - it seemed like a “bug” that should be fixed. Maybe my bosses just needed to relax a bit. That way my responsibility would shrink to match my control. Or maybe I needed better comms, better marketing - some way of making sure people came. That way my control would expand to match my responsibility. Either way, the gap between responsibility and control should be eliminated somehow.

And then I had kids - three of them. As a dad I am responsible for my children. But I am not in control of them - sometimes I can barely get them to eat their tea. And so worry worms its way in - through that gap between responsibility and control. But I began to realise that when it comes to my kids, I just can’t close the gap and I shouldn’t even try. To abdicate responsibility or to seek control are just two different flavours of failure. The gap between them isn’t a bug in the code of life, it’s a feature. It’s part of being human, and so human flourishing means learning to live well with, even in, that gap. But how?

In the earliest record we have of Christians trying to explain themselves, a book of the Bible called (confusingly) Acts, we follow Paul, convert to Christianity, to Athens, the cultural capital of the ancient world. And there he meets people different from us in almost every way… except that like us they are worriers. And they are worried because they feel responsible for something they can’t control. Paul finds an altar with this inscription “to an unknown god”. What makes people erect an altar to an unknown god? The worry that worms its way in between responsibility and control. We’re not sure if we know about all the gods - we’re not in control. But that god we don’t know about might hold us responsible. So let’s try to close the gap by erecting an altar to a god we don’t even know.

Paul offers a better solution - to them and to us. He’s invited to give a speech to the leaders figures of Athens, but he doesn’t present his audience with a more sophisticated technique for closing the gap between responsibility and control. Rather, he introduces them to his God, to the truth that allows us to flourish in that gap. This God, Paul says, marks out the appointed times and places of all people: that is, he is in control of all things. This God, Paul says, wants everyone to seek him and find him: that is, he wants the best for all people. This God, Paul says, doesn’t need anything from us: that is, our responsibility is his invitation to be part of what he’s doing in the world. Know this God, trust this God, Paul says, and you can see the gap between responsibility and control as a feature of life and not a bug. You can flourish in and not worry about the gap.

But how does that work in the midst of tea-time tantrums and the day-to-day worries of life? Well for me, on a good day, it works a bit like this. When I’m confronted with the reality of quite how much is beyond my control, I’m not faced with chaos. I’m just faced with the fact that I’m not God, but God is - and nothing is beyond his control. And the God who is in control when I’m not loves my kids more than I do, better than I do. And he doesn’t need me. He’s not delegated responsibility for my kids to me because he’s too busy to look after them himself. I’ve been given the responsibility of being their dad so I get to share in the joy of watching them grow into all they were made to be. The gap is still there - I’m really responsible and I’m really not in control. But maybe I’m ok with that.

There may well be certain features of the modern age that heighten our anxiety. But the people of first century Athens didn’t have smartphones or face climate change and they still worried. Because they felt responsible for something they didn’t control, just like we do. It’s an ancient problem, a feature not just of our culture, but of being human. And what if an ancient problem needs an ancient solution?

Celebrate our 2nd birthday!

Since March 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free. This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief