“It’s tough to be happy in tennis because every single week, everyone loses apart from one person.”

Taylor Fritz – American World Number 9 tennis player

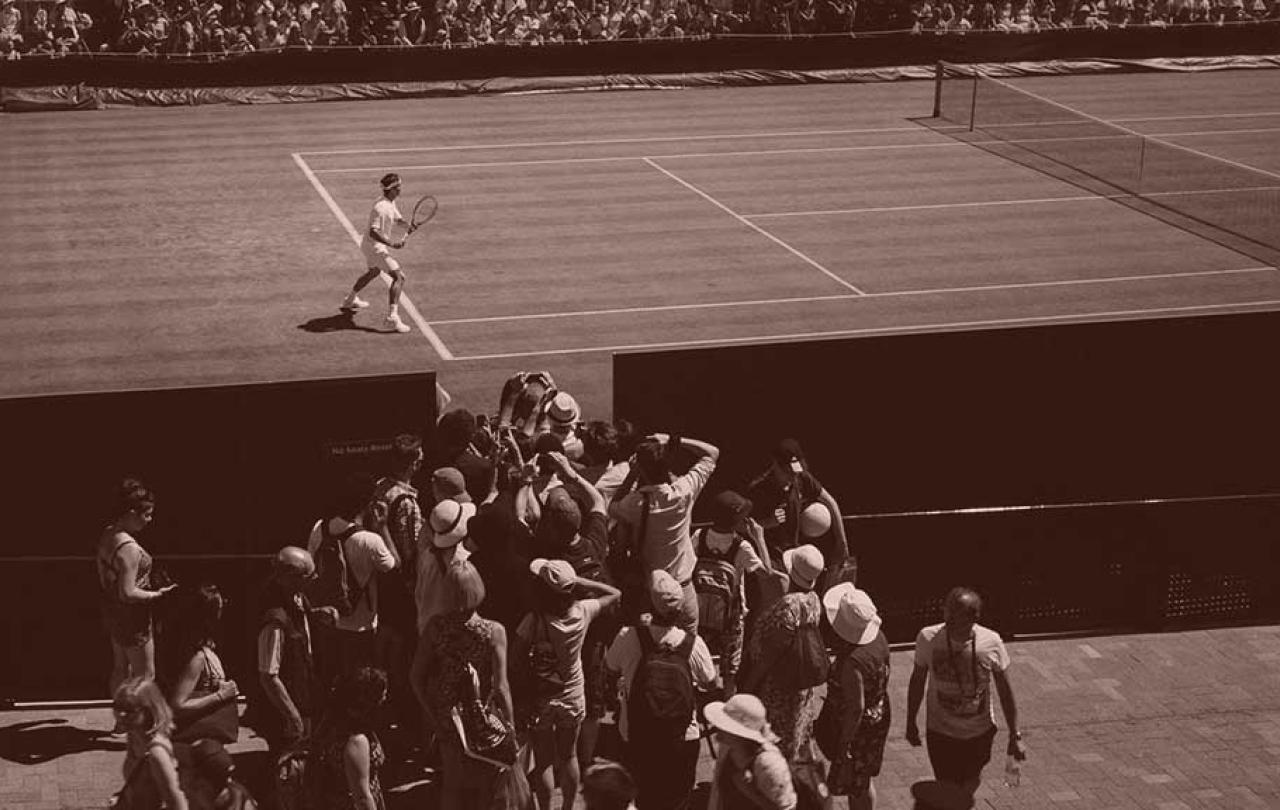

Wimbledon is one of the pinnacles of the tennis season as players long to win the prestigious tournament. Yet only a handful will experience success. The vast majority will fail in their goal and return to the treadmill of elite touring sport.

These players were once the best in their town, state or country, yet now they face the relentless pressure of competing against hundreds of others who were ‘best-in-class.’

Former US Open champion Bianca Andreescu struggled to come to terms with this reality when she turned professional. Speaking in the Netflix documentary series Break Point, she said:

“When I started losing, I didn’t know what was happening in a way. I didn’t know how to deal with it. I was shocked, which was really weird because people are losing every single week in tennis.”

The shame of losing

Andre Agassi has written one of the most illuminating autobiographies of any sportsperson, where he recounts how by the age of seven, he associated winning tournaments with safety from the potential rage and disappointment of his highly driven father.

However, having won Wimbledon at the age of 22, he discovered that even winning one of the biggest tournaments in his sport could not heal his wounds and the need to find satisfaction and worth in his performance. He said after his victory:

“winning changes nothing. Now that I’ve won a slam, I know something that very few people on earth are permitted to know. A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad, and the good feeling doesn’t last as long as the bad. Not even close.”

Like all humans, elite athletes need to know they have value and significance not based on what they have done or will do in the future but on who they are.

More recently Emma Raducanu, the British 2021 US Open Champion reflected on how she had become trapped in a similar view of her tennis.

"I very much attach my self-worth to my achievements,"

she said.

"If I lost a match I would be really down, I would have a day of mourning, literally staring at the wall. I feel things so passionately and intensely."

Ashley Null is an experienced sports chaplain who has worked with Olympians and high-level sportspeople for many years. In reflecting on the story of Agassi, he notes:

“The first task of any chaplain to elite athletes is to help them learn to separate their personal identity from their athletic performance. Only love has the power to make human beings feel truly significant, not achievement. Only knowing that they are loved regardless of their current performance can make Olympians feel emotionally whole.”

How to feel emotionally whole in elite sport

Current professional player Shelby Rogers has noted that in elite tennis:

“Week to week, you’re walking around with your ranking plastered on your face.”

They cannot seem to escape their performances.

Like all humans, elite athletes need to know they have value and significance not based on what they have done or will do in the future but on who they are. Most of us do not have our work watched by millions and instantly ranked and analysed. But for elite athletes, these pressures mean they are especially vulnerable to insecurity and are much more likely to conflate identity with performance. Thus, a stable and secure identity is critical for the sportsperson.

Sports psychology has begun to understand this need and now encourages athletes to think more broadly about how they find their worth and value. Rebecca Levett has worked in a number of high-performance environments and acknowledges that:

“It is absolutely vital that we, as support staff and coaches encourage our athletes to consider who they are as a person as well as an athlete.”

For most of us our ‘private identity,’ as Levett calls it, could be derived from our family and friends and how they see us. Several athletes reference their role as husband or wife or mother and father as key in their success. Meanwhile, others, recognising that not even family relationships are permanent or always fulfilling, have turned to Christian faith for this stability.

Shelby Rogers recently spoke on a podcast about the difference understanding this has had on her tennis career.

“As much as you try not to read the media, you still have that constant comparison, and so it is understanding within yourself that you do not have to prove yourself to God…that you do not have to perform for him…you just have to go out and enjoy yourself and use these gifts he’s given you.”

The Christian message is that a secure identity can be found in God's assured, steadfast love, as a Father has for his children.

Sport is a beautiful gift, but it is not stable enough to define us.