These days I can’t seem to avoid the spectre of loneliness. Bob Geldof recently described Sinead O’Connor as ‘full of a terrible loneliness’ in the weeks before she died. Elon Musk, who owns Twitter, one of the world’s greatest social networks, was recently described as a cutting a lonely figure. Even more widely, over a quarter of all Londoners say they often or always feel lonely - and that in a city where you can’t get away from people – all 8 million of them.

Loneliness is an epidemic these days. In the UK we even have a Minister for Loneliness and a Department of Government offering ‘Loneliness Engagement Fund’ grants for groups coming up with good ideas to combat it. Loneliness, as Roger Bretherton writes, causes psychological and social damage and is one of the main threats to mental health in contemporary life. I would hazard a guess that if you’re reading this there are times you feel isolated, and would love to have a greater sense of community where you live, or richer friendships. If you don’t, then count yourself fortunate.

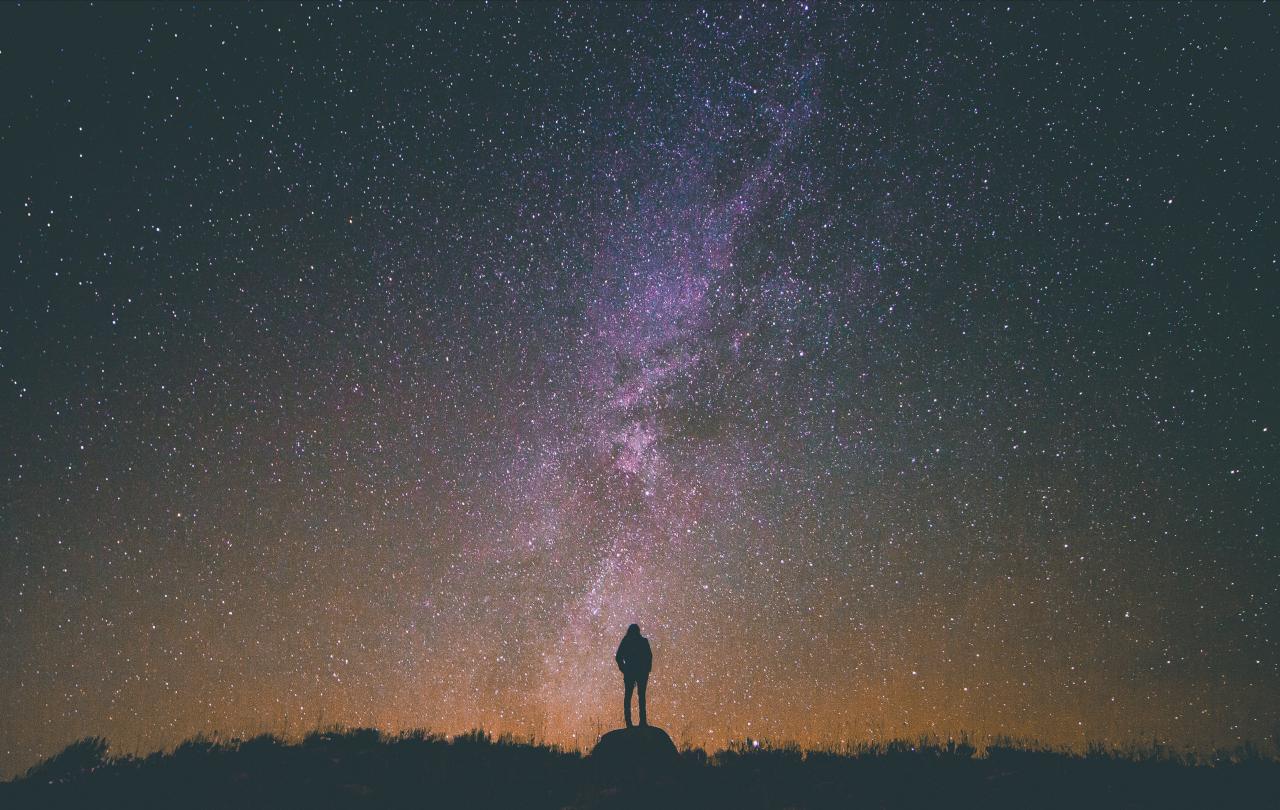

Underneath our immediate sense of isolation, our social unease, the ache in the soul that comes with feeling out of connection with others, lies a deeper sense of cosmic loneliness.

During the pandemic, looking around for books that would shed some light on that strange experience of isolation as so many did, I re-read two novels: Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe published in 1719, and Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo, published in 1904. In both stories, people get stranded on deserted islands. Somehow lockdown didn’t seem that different.

Everyone knows the story of Robinson Crusoe. You might have thought that being the sole survivor of a shipwreck, alone on a remote island, would lead to a crisis of loneliness and self pity. Well, he does have moments when he reflects on the possibility that he might die in that desolate place, and remarks how ‘the tears would run plentifully down my face when I made these reflections.’ But the self pity doesn't last long. He goes on to ask himself the question of why he alone was saved out of all crew of the ship that foundered. He sees some kind of providential design in this - that he has been saved, not just by chance, but for some wider purpose, which gives him a sense of comfort. In fact, the novel is the tale of a kind of spiritual awakening, as he gradually sees in his story something of the hand of God mysteriously guiding and preserving him through his trials. Seeing this enigmatic hand directing his affairs, and discerning some kind of purpose in his isolation, Crusoe sets about the tasks of building a kind of small civilization on his island, constructing increasingly sophisticated shelters, planting crops, capturing and taming animals, mapping the island, until his final rescue. He is alone (until Man Friday appears of course) but strangely not alone.

In Conrad’s Nostromo, it turns out very different. This is a story of attempts to protect a hoard of silver from revolutionaries in the troubled (and fictional) South American republic of Costaguana. In the course of trying to hide the treasure, alongside Nostromo, the main figure in the story, the politically ambitious and romantic journalist Martin Decoud, also finds himself stranded on a deserted island, albeit with the load of valuable silver for company. His experience however is totally different. He has no such belief in providence and so for him, the isolation bears more heavily: “solitude appeared like a great void, and the silence of the gulf like a tense, thin cord to which he hung suspended by both hands, without fear, without surprise, without any sort of emotion whatsoever…” Unable to bear the isolation, the aimlessness of his life on the island, and the apparent failure of his plans and projects, he fills his pockets with silver ingots from the treasure, rows in a small dinghy a short way out from the shore, shoots himself with a revolver and falls overboard, sinking slowly to the bottom of the sea. And so, as Conrad describes it, in a cold, yet superb turn of phrase: “the brilliant Don Martin disappeared without a trace, swallowed up in the immense indifference of things.”

Even though they both faced isolation and loneliness, the fates of these two characters are very different. One is a story of spiritual growth, learning, meaningful activity and ultimate rescue. The other is a tragedy of lost hope and potential. It touches the heart, yet remains a tragedy.

Is it surprising that when we tell ourselves that we are alone in the cosmos, that there is no-one there to hear our cries or heartfelt longings, that the aching hole in the universe finds its way into our own hearts?

Of course, both are novels not historical episodes, yet the two books, separated by nearly 200 years, operate in very different frameworks. The first operates in a world which assumes a kind of providential ordering of things. The working of a divine hand of providence is, as Crusoe (and presumably Defoe) realises, hard to discern and difficult to distinguish in any one moment, and so leads many to doubt it is there at all. Belief in providence has always been a choice - an act of faith rather than a scientifically proved theory. And yet the story is framed within the overall belief that in the strange twists and turns of life there is a deeper divine order that leads towards a distinct purpose of good and which makes human activity directed towards that purpose meaningful.

The other story has lost that sense of divine order, and is left only with the “immense indifference of things.” This is a world in which there is nothing beyond what we can see and feel, no objective purpose, direction or goal other than that dreamed up by us. Human activity, in this case, the search for wealth and riches, seems strangely pointless. All that is left is human love and relationship and when that becomes impossible, due to enforced loneliness, there seems little point left to life.

Richard Dawkins famously wrote: ‘the universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is at bottom no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference.’ For the moment I'll leave to one side the question of whether the universe does point in that direction, but either way, if we tell ourselves that story, as we have so often been doing for the last couple of centuries, is it surprising that often we feel dreadfully alone? Is it surprising that when we tell ourselves that we are alone in the cosmos, that there is no-one there to hear our cries or heartfelt longings, that the aching hole in the universe finds its way into our own hearts? It doesn’t take much imagination to see that the ‘immense indifference of things’ leaves a hollowness in the heart of life and the pit of the stomach.

Such a deeper cosmic loneliness might explain why we can still feel alone even in a city, even in a crowd or even sometimes among our friends. It helps us see our loneliness not just as a tragedy but as a pointer towards our need from greater sense of connection than any human being could give.

In Matthew’s gospel, the very last sentence depicts Jesus saying to his perplexed but bewildered disciples, scarcely daring to believe that he has actually risen from the dead: “Surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” This simple promise is one that has held and sustained Christians for generations, in prison cells, through dangerous voyages, through purges, in times of persecution, misunderstanding and sickness and, yes, times of loneliness in modern western societies. Of course, we need a sense of belonging, and the company of others, as we are made for that. But underneath it we need a deeper connection, a bond with something, or someone at the very heart of things. Such a promise doesn’t remove loneliness, but it makes it bearable, even meaningful.