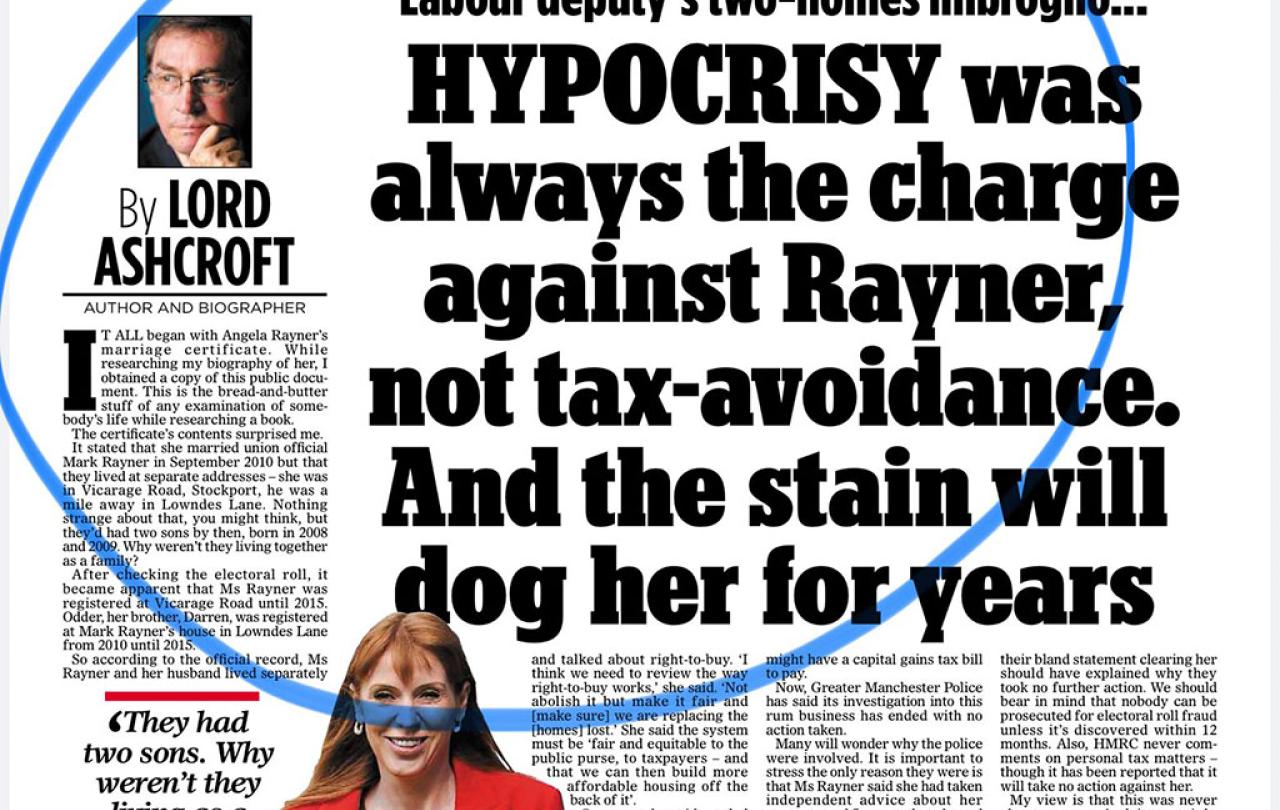

Lord Ashcroft launched an extraordinary new attack on Labour’s deputy leader, Angela Rayner, in the Mail on Sunday at the start of this week, claiming that his investigation into where she lived, allegedly for tax purposes, was never about money.

“Hypocrisy was always the charge against Angela Rayner,” he intoned, “not tax avoidance… And the stain will dog her for years to come.”

Leaving aside whether stains dog people or the other way around, this is extraordinary not because Ashcroft attacks a senior Labour figure – day follows night, etc – but because it’s the sort of volte face that journalists call a reverse ferret.

Had Rayner been found by investigating police officers to have committed a tax-fraud or electoral offence (and, to be clear, they didn’t), we need to ask ourselves whether Ashcroft would have run with the same line.

Imagine: “Angela Rayner has committed a crime, but this is really about hypocrisy.” Do you think he’d have gone with that? Neither do I.

Usually, charges of hypocrisy are levelled at politicians who use social privileges to which they’re opposed in principle.

Hypocrisy is invariably the charge when there’s nothing else to go with. And that must raise questions about what hypocrisy really is.

It’s clearly not just about telling lies. In the first televised debate this week between Rishi Sunak and his rival for premiership, Keir Starmer, the former repeatedly (12 times) claimed that Treasury officials had independently calculated that the latter’s spending plans would add £2,000 to the tax bill of every family in the UK. A published letter subsequently showed that the Treasury had specifically told the Government that this figure was bogus and not to be used.

Was this hypocritical? No, it was just plain wrong – in the sense of both inaccurate and immoral. The opportunity for hypocrisy came when both leaders were asked whether they would use private healthcare for a family member in need. Sunak said he would; Starmer said he wouldn’t. If Starmer now ever uses private health facilities, Mr Hypocrisy will be ringing his door bell.

From this, we deduce that hypocrisy is pretending to be what you’re not. So Donald Trump poses as a great statesman, the saviour of his nation, but goes down for all 34 felony charges of falsifying accounts to hide his pay-off of former porn actor Stormy Daniels, in order to protect his electoral prospects. That’s hypocrisy, precisely because he’s pretending to be someone he isn’t.

That hypocrisy is exacerbated when Trump holds up a Bible to support his authority – or, indeed, publishes his own. Likewise, when a rich TV evangelist is convicted of sexual abuse (there are, tragically, too many examples to choose from).

By contrast, is Rayner pretending to be something she isn’t because her family has used two properties? Very probably not. Similarly, we might like to ask whether SNP deputy leader Kate Forbes is a hypocritical politician because she’s a Christian, or a hypocritical Christian because she’s a politician. Very probably neither. Being both is who she is.

Usually, charges of hypocrisy are levelled at politicians who use social privileges to which they’re opposed in principle. Like when Labour MP Diane Abbott sent her son to a fee-paying school. Private education, like private healthcare, is only meant to be available to those who support it ideologically, rather than just financially. Otherwise, it’s hypocrisy.

The problem here is the presumption that the private sector is only available to those who endorse it. So it’s hypocritical for socialists to use it. But that presumption moves very close to the view that working people should know their place (a social order, incidentally, that the Christian gospel defies).

There is no inconsistency – and consequently there can be no hypocrisy – in wanting the best for our own children, while concurrently wanting the best for all children. One might even call such a policy something like levelling-up, should such a thing exist.

We may not know what Angela Rayner’s shortcomings are, but simply having them doesn’t make her a hypocrite.

A biblical definition of hypocrisy might be the hiding of interior wickedness under an appearance of virtue. In Matthew’s gospel, it’s the charge levelled at Pharisees whose good deeds are entirely self-serving.

In this manner, moral theology would point to hypocrisy being the fruit of pride. But simply to hide one’s own shortcomings isn’t necessarily to be construed as hypocrisy, because there’s no moral obligation to make them public.

In that context, we may not know what Angela Rayner’s shortcomings are, but simply having them doesn’t make her a hypocrite. Otherwise, we’re all hypocrites (and there may be some truth in that).

It reduces to resisting the temptation to point to the mote of hypocrisy in our neighbour’s eye, while failing to attend to the beam in our own. That would also be to avoid self-deception. The kind of deception that pretends that one’s actions are in the public interest, when clearly they are only serving your own. Which, neatly enough, brings us back to Lord Ashcroft.