J.C. Kumarappa (1892 – 1960) was an Indian economist, writer and freedom fighter in the Indian Independence Movement. Widely regarded as the most influential Christian of the India’s independence struggle, Kumarappa’s most notable contribution was as the father of Gandhian economics. Informed by a lifetime of travel through rural India, Kumarappa fused Gandhian thought with Christian ethics to create a school of economics that is difficult to place within the traditional Western understanding of the political spectrum.

Fusing traditionalist perspectives on economics with a radical commitment to universal upliftment, Gandhian economics was regarded by many as being too idealistic for real world application. But in an era where twentieth-century notions on the inherent superiority of central planning, material consumption and economic growth for its own sake are being increasingly questioned, it may be worth revisiting this school of thought, its early achievements and its founding father.

Early Life

J.C. Kumarappa was born on January 4, 1892, in what is now Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India. The son of a well to do civil servant and the grandson of a Lutheran Pietistic Minister, his family descended from some of India’s earliest Protestant converts.

His parents were strong believers in Pietistic notions of morality and charity. Kumarappa’s father was a strong proponent of academic achievement and professional success, encouraging all his children, including daughters, to pursue higher education and careers.

Kumarappa’s mother believed in the importance of imparting a sense of personal responsibility and concern for the poor to her children. A defining experience of Kumarappa’s childhood working alongside his siblings to raise chickens and turkeys for sale in the market, with all proceeds going to support his mother’s charitable endeavors.

Though most readers would nod approvingly at the Kumarappa’s parenting strategies they were ahead of their time in many ways. Facilitating higher education for their daughters at a time when even many upper-class Indian women were illiterate and encouraging their children to raise chickens in a society where the upper classes recoiled at the thought of performing any sort of manual labour.

In keeping with the high academic and professional expectations of his family, Kumarappa would go on to study history before departing for London in 1913 to pursue an accounting apprenticeship. Unlike many Indian independence activists, including Gandhiji, Kumarappa steered clear of the political activism that was becoming increasingly mainstream among Indian students studying in the UK.

A regular church goer at first, he grew disillusioned by the British church’s active support for World War I war efforts and became increasingly influenced by Christian Pacifist war resistors. He returned to India in 1919 to pursue a career as a successful accountant before travelling to the United States in 1927, at the age of 35, to pursue a business degree at Syracuse University.

By this time, Kumarappa had psychologically detached himself from the organized church in favor of independent spiritual practice. Kumarappa was not alone in this. The ascetic, Sadhu Sundar Singh, and the women’s rights advocate, Pandita Ramabai, regarded as the mother of Indian Pentecostal Christianity are two other notable Indian Protestant figures, from the twentieth-century, also rejected formal church affiliation. In all three cases, an intense Christian devotion coexisted alongside a sense of disillusionment over the organized church’s support for the British Raj.

With his spiritual transformation complete, Kumarappa’s time in the United States marked the start of his political awakening. Following the lead of two of his elder brothers, who had already joined the independence movement, Kumarappa grew increasingly disillusioned by the actions and attitudes of the British Raj. He published Public Finance and India’s Poverty, a critical analysis of British colonialism’s economic exploitation of India. The publication was disseminated internationally and widely read by many including Gandhiji himself.

He also expressed skepticism in the unchallenged belief that technological innovation was always a net good.

Kumarappa had returned to India in 1929, where after his request for an audience with Gandhiji was approved, he became a full-time independence activist and adherent of the Gandhian social movement. His first undertaking included an assessment of the economic state of rural India, something which had previously only be done from the perspective of the British colonial government and would eventually go on the become the editor of Young India, the official English language newspaper of the Gandhian movement. It was through this work that Kumarappa began to develop a school economic thought he dubbed Gandhian economics.

Gandhian economics

Inspired by the teachings of Gandhiji along with his own Christian worldview, Gandhian economics served as an indigenous alternative to the dominant ideologies of capitalism and socialism. Kumarappa recognized that contemporary Indian society was plagued by extreme poverty, low-social trust, and systemic exploitation of the rural majority at the hands of the colonial state, feudal landlords and caste hierarchy. However, he was unconvinced of capitalism and socialism’s ability to effectively address these issues, fearing their propensity to centralize decision making authority in the hands of a few, be they bureaucrats or CEOs, would only further disenfranchise ordinary Indians.

He also expressed skepticism in the unchallenged belief that technological innovation was always a net good and believed technology should be critically assessed to evaluate whether it advances the interests and values of the communities they serve.

The six pillars of Gandhian economics include the concepts of:

1. Sarvodaya (universal upliftment): Gandhian economics believed economic development must focus around achieving welfare and upliftment for all people, including those who have been historically marginalized. The emphasis on Sarvodaya is also why Gandhian economics should not be confused with reactionary political thought which emphasizes the preservation of traditional social and economic institutions for the benefit of the elite.

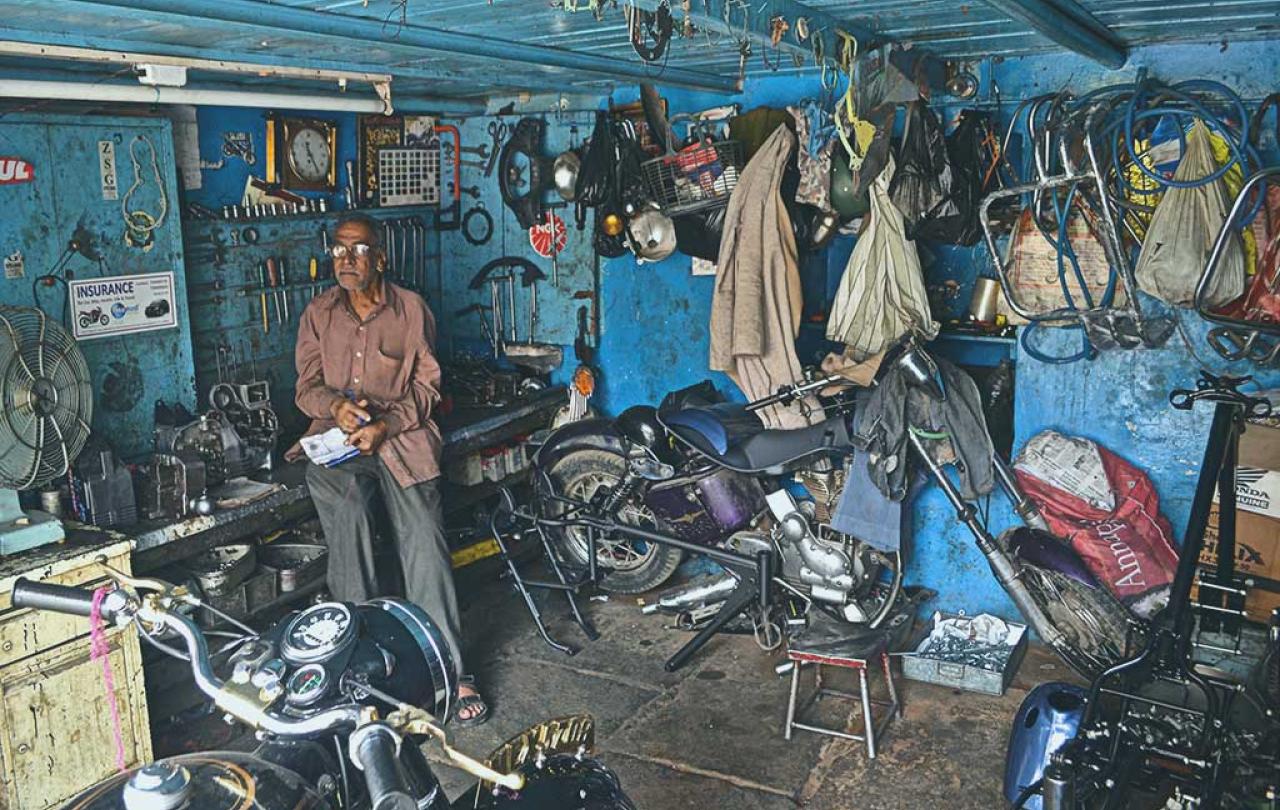

2. Decentralization: The decentralization of decision-making authority is necessary to protect individual autonomy and empower communities. Kumarappa believed that centralized authority and the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few would lead to exploitation and disenfranchisement, regardless of the prevailing ideology. Kumarappa argued that an emphasis on small scale industries and local self-sufficiency would be more effective as a means of poverty alleviation in India.

3. Trusteeship: Gandhian economists believed that a decentralized economy would limit extreme concentrations of wealth but recognized that class differences would likely never truly disappear and thus believed that wealthy individuals be encouraged to engage in the voluntary redistribution of wealth.

4. Swadeshi (self-reliance): Gandhian economics was skeptical of globalization and believed in economic self-reliance at the national and local level with the aim of reducing dependence on foreign imports.

5. Nonviolence: Gandhian economics advocated non-violence which when taking an economic perspective includes avoiding practices such as usury, hoarding and predatory lending.

6. Environmental sustainability: Gandhian economics believed that environmental stewardship and the sustainable use of natural resources were key to ensuring the long-term wellbeing of society and that this was best achieved by giving local communities autonomy and decision-making authority over their resources and local environments.

The impact of Gandhian economics

Though the tenets of Gandhian economics often come across as overly idealistic, the ideology inspired several major economic movements during the Indian Independence Movement. The All India Village Industries Association (AIVIA) was established by Gandhiji and Kumarappa in 1934 with the aim of identifying best practice solutions that could be disseminated to promote village industries and improve economic self-reliance

One early initiative undertaken by the AIVIA was to address rural India’s dependence on foreign kerosene and kerosene lamps for lighting, at a time when rural electrification was extremely rare. AIVIA technicians worked to develop the magan dipa, a locally produced alternative to kerosene lamps that could operate on domestic supplies of non-edible vegetable oils. Aside from the employment generated through the manufacturing of magan dipas, the newly created demand for locally produced non-edible vegetable oil incentivized Indian farmers to process their oilseed crops locally rather than sell them for export. This would boost employment through the establishment of oil presses and also provide farmers with a new stream of income as they could now rent out their cattle to power oil presses. AIVIA believed that solutions like the magan dipa could create economic growth at the local level and improve the quality of life for India’s rural majority without the need for an industrialized export driven economy.

Gandhian economic principles also manifested as social movements such as Gandhiji’s call for the boycott of imported clothing from Britain in favor of locally produced homespun clothing. The impact of the boycott led to a 20% decline in sales among British clothing exporters and an upsurge in local clothing manufacturing.

Throughout all this, Kumarappa played a central role in the real-world application of Gandhian economics and was widely considered to be a major figure in the Indian Independence Movement. His activities landed him in prison on more than one occasion with his most notable stint being in 1942 where he penned two of his most famous texts. The first being The Economy of Permanence, which summarized the rationale and principles of Gandhian economics, and the second being the Practice and Precepts of Jesus, which contained his religious views on Christianity and the teachings of Jesus Christ. As his prison sentence progressed Kumarappa developed a severe kidney ailment that led to his premature release. He gradually recovered on the outside and soon resumed his activist duties.

Kumarappa’s later life

After India’s independence, in 1947, Kumarappa worked for the Planning Commission of India which sought to develop national policies for agriculture and rural development. During this time, he travelled widely throughout East Asia and Europe to study various rural economic systems. However, a rift between him and the post-independence political establishment quickly began to form.

Despite the early victories of Gandhian economics, the post-independence Indian establishment came to view the field with extreme skepticism, despite lionizing its early achievements as major victories of the Indian Independence Movement. The Congress Party, with whom Gandhiji was aligned with, adopted a more mainstream attitude to economics viewing industrialization, urbanization and the centralization of decision making through modernized bureaucracies as imperative for India’s development.

Furthermore, decades as an independence activist made it difficult for Kumarappa to adjust to the conformity and hierarchy of the Indian bureaucracy and he quickly developed a reputation for outspokenness and defiance and did not hesitate to openly criticize his own government’s mismanagement and ineptitude. The Congress government began to view him as a growing irritant but were limited in their ability to control him. The public viewed Kumarappa as an incorruptible advocate for India’s rural poor and a hero of the independence era which meant disciplinary action would likely harm the government’s reputation more than Kumarappa’s.

Kumarappa grew increasingly disillusioned with the Planning Commission which he believed was staffed by out-of-touch bureaucrats who lacked a personal understanding of the rural poor and the economy of rural India. By 1954, Kumarappa’s declining health forced him to retire from his public duties though he remained as staunchly committed to his Gandhian ideals urging followers that work towards achieving sarvodaya and swadeshi though their own personal and community efforts rather than relying on the “superficial schemes” of the Government. And on January 30, 1960 Kumarappa passed away following a paralytic stroke that had overtaken him four days earlier. The Kumarappa Institute of Gram Swaraj was established in his honour and continues to operate to this day by working to promote economic opportunities for India’s rural poor.

Conclusion

As the twentieth-century progressed, Gandhian economics gradually faded into obscurity, often viewed as too naïve for the real world. And maybe it was in some ways. Gandhian attempts at voluntary land redistribution failed almost everywhere, except in Telangana where they succeeded in part because landlords were growing increasingly fearful of the region’s growing Communist insurgency. But the core principle of Gandhian economics, the belief that economic growth can come about through grassroots organizing at the community level remains relevant. In his book Everybody Loves a Good Drought, journalist Palagummi Sainath, documents the dehumanizing poverty hundreds of millions of Indians experience and how the Indian state frequently exacerbates their situation through social, economic and political disenfranchisement. Villagers who find their public schools and clinics mismanaged by apathetic officials, entire communities are branded as born criminals and treated as such, and a Kafkaesque bureaucracy consistently drags progress to a near standstill.

Yet Sainath also describes hopeful tales of what happens when the poor are given the opportunity to take matters into their own hands. In one of his most inspiring case studies, Sainath describes what happens when illiterate, landless, female stone quarry workers are given the opportunity to form a cooperative society entirely managed by them. Within a few short years these women establish a system that boosted productivity, wages for themselves and even taxes collected by the state. Health and safety were improved, adult education classes instituted. The women even began publishing their own newsletter. The improvements contrast greatly with a similar quarry which decided to join a professionally managed cooperative society only to end up with half their income deducted to fund the salaries of the white-collar professionals now tasked with their supposed wellbeing. Likewise, across India, the fight for environmental protection and regeneration is often being led by local communities. One notable example being how the village of Lapodiya in India’s arid Rajasthan state came together to transform their communities water table and is now seen as a role model for water conservation across the country. Watch the video below.

The successful self-organization of both these communities is exactly what Kumarappa believed would happen when we as a society respect the personal and economic autonomy of individuals and communities and shift decision making power from the top of the pyramid to its bottom. Too often, in India and across the world, the poor are infantilized as being incapable of improving their own lives without the outside intervention of the state, private enterprise or professionally managed not-for-profits. Maybe Gandhian economics can help us revisit this harmful assumption and reassess how it has been used to inadvertently disenfranchise the poor across the world.