Google got itself into some unusual hot water in recently when its Gemini generative AI software started putting out images that were not just implausible but downright unethical. The CEO Sundar Pichai has taken the situation in hand and I am sure it will improve. But before this episode it was already clear that currently available chat-bots, while impressive, are capable of generating misleading or fantastical responses and in fact they do this a lot. How to manage this?

Let’s use the initials ‘AI’ for artificial intelligence, leaving it open whether or not the term is entirely appropriate for the transformer and large language model (LLM) methods currently available. The problem is that the LLM approach causes chat-bots to generate both reasonable and well-supported statements and images, and also unsupported and fantastical (delusory and factually incorrect) statements and images, and this is done without signalling to the human user any guidance in telling which is which. The LLMs, as developed to date, have not been programmed in such a way as to pay attention to this issue. They are subject to the age-old problem of computer programming: garbage in, garbage out.

If, as a society, we advocate for greater attention to truthfulness in the outputs of AI, then software companies and programmers will try to bring it about. It might involve, for example, greater investment in electronic authentication methods. An image or document will have to have, embedded in its digital code, extra information serving to authenticate it by some agreed and hard-to-forge method. In the 2002 science fiction film Minority Report an example of this was included: the name of a person accused of a ‘pre-crime’ (in the terminology of the film) is inscribed on a wooden ball, so as to use the unique cellular structure of a given piece of hardwood as a form of data substrate that is near impossible to duplicate.

The questions we face with AI thus come close to some of those we face when dealing with one another as humans.

It is clear that a major issue in the future use of AI by humans will be the issue of trust and reasonable belief. On what basis will we be able to trust what AI asserts? If we are unable to check the reasoning process in a result claimed to be rational, how will be able to tell that it was in fact well-reasoned? If we only have an AI-generated output as evidence of something having happened in the past, how will we know whether it is factually correct?

Among the strategies that suggest themselves is the use of several independent AIs. If they are indeed independent and all propose the same answer to some matter of reasoning or of fact, then there is a prima facie case for increasing our degree of trust in the output. This will give rise to the meta-question: how can we tell that a given set of AIs are in fact independent? Perhaps they all were trained on a common faulty data set. Or perhaps they were able to communicate with each other and thus influence each other.

The questions we face with AI thus come close to some of those we face when dealing with one another as humans. We know humans in general are capable of both ignorance and deliberate deception. We manage this by building up degrees of trust based on whether or not people show behaviours that suggest they are trustworthy. This also involves the ability to recognize unique individuals over time, so that a case for trustworthiness can be built up over a sequence of observations. We also need to get a sense of one another's character in more general ways, so that we can tell if someone is showing a change in behaviour that might signal a change in their degree of trustworthiness.

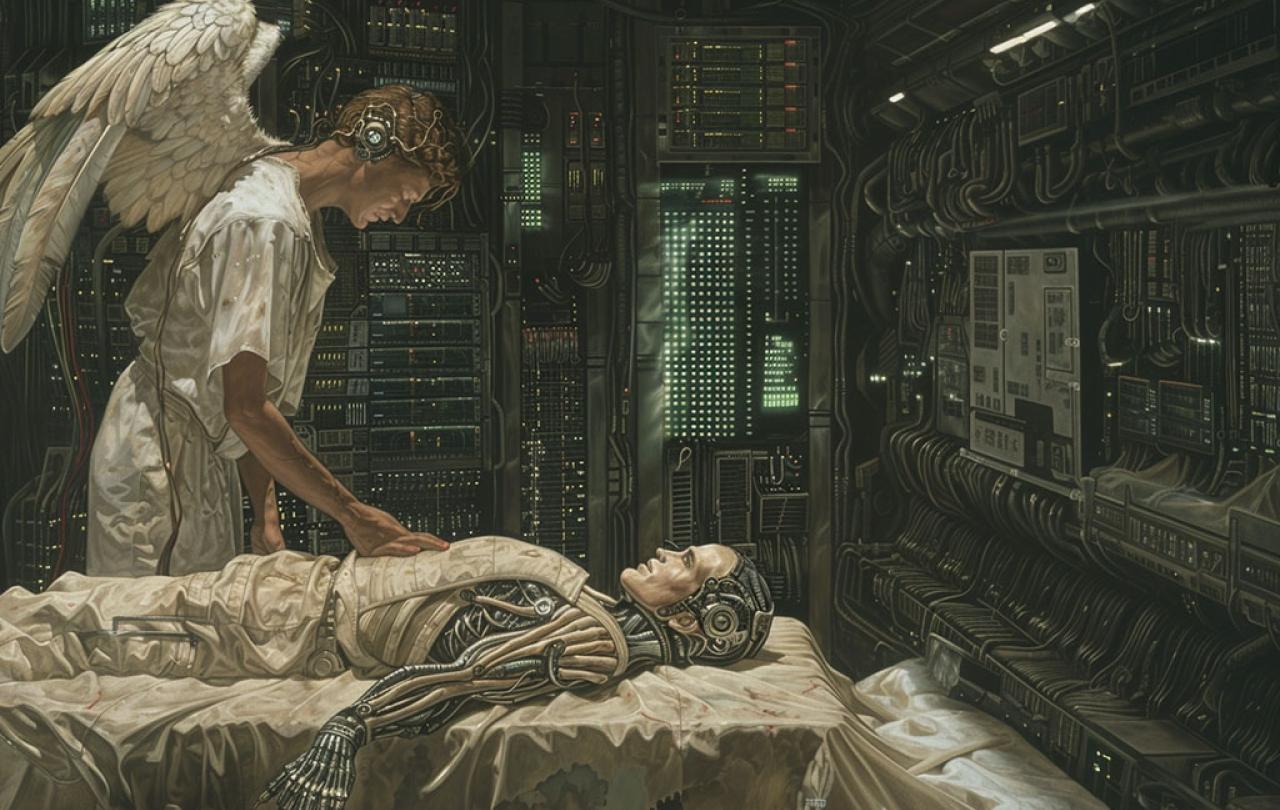

In order to earn our trust, an AI too will have to be able to suffer and, perhaps, to die.

Issues of trust and of reasonable belief are very much grist to the mill of theology. The existing theological literature may have much that can be drawn upon to help us in this area. An item which strikes me as particularly noteworthy is the connection between suffering and loss and earning of trust, and the relation to mortality. In brief, a person you can trust is one who has ventured something of themselves on their pronouncements, such that they have something to lose if they prove to be untrustworthy. In a similar vein, a message which is costly to the messenger may be more valuable than a message which costs the messenger nothing. They have already staked something on their message. This implies they are working all the harder to exert their influence on you, for good or ill. (You will need to know them in other ways in order to determine which of good or ill is their intention.)

Mortality brings this issue of cost to a point of considerable sharpness. A person willing to die on behalf of what they claim certainly invests a lot in their contribution. They earn attention. It is not a guarantee of rationality or factual correctness, but it is a demonstration of commitment to a message. It signals a sense of importance attached to whatever has demanded this ultimate cost. Death becomes a form of bearing witness.

A thought-provoking implication of the above is that in order to earn our trust, an AI too will have to be able to suffer and, perhaps, to die.

In the case of human life, even if making a specific claim does not itself lead directly to one's own death, the very fact that we die lends added weight to all the choices we make and all the actions we take. For, together, they are our message and our contribution to the world, and they cannot be endlessly taken back and replaced. Death will curtail our opportunity to add anything else or qualify what we said before. The things we said and did show what we cared about whether we intended them to or not. This effect of death on the weightiness of our messages to one another might be called the weight of mortality.

In order for this kind of weight to become attached to the claims an AI may make, the coming death has to be clearly seen and understood beforehand by the AI, and the timescale must not be so long that the AI’s death is merely some nebulous idea in the far future. Also, although there may be some hope of new life beyond death it must not be a sure thing, or it must be such that it would be compromised if the AI were to knowingly lie, or fail to make an effort to be truthful. Only thus can the pronouncements of an AI earn the weight of mortality.

For as long as AI is not imbued with mortality and the ability to understand the implications of its own death, it will remain a useful tool as opposed to a valued partner. The AI you can trust is the AI reconciled to its own mortality.