Listen to Good People

Whenever I bump into the familiar sounds of a Mumford & Sons song, it’s 2013 and they’re headlining the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury. I can close my eyes and see the whole scene before me; it’s all trumpets and tweed. But when I take a moment, and home in on the lyrics, it’s a different scene that I see. There’s a story in the Bible where a man, Jacob, spends a night physically wrestling with God, it’s all dirt and elbows, the created grappling with the creator. And, occasionally, when listening to Mumford & Sons’ catalogue, I feel as though I’m watching that scene play out. I’m listening to souls laid bare, I’m witnessing people gripping the divine in the dirt. I get the sense that their lyrics have been born of a wrestling match, not a writing session; they’re crafted by people who are limping out of a tussle with truth.

Mumford & Sons – Marcus Mumford, Ben Lovett and Ted Dwane - seem to have largely grown out of their 2013 selves. But, if their new single is anything to go by, they haven’t grown out of wrestling their lyrics into existence.

From the first line until its last, this song has but one message to proclaim: change, the redemptive kind, is at hand.

Good People is the first track that they’ve released in five long years, and offered up in partnership with the mighty Pharrell Williams, it has been lorded as the collaboration that nobody saw coming. Speaking of the collaborative process, the band wrote that,

‘...this song came together fast. Like, in a day. We haven’t relied on immediate instincts like that, really, since the very early days of our band. It has felt fast and loose and really, really fun.’

The additional presence of Native Vocalists, a six-piece choir hailing from Native American Tribes within the northern Great Plains, makes this track a mosaic of musical influences. But we should have expected this, Pharrell’s insatiable creative curiosity has taken him to some unexpected places, an alternative-folk song is merely his latest destination. What’s more, it is a destination that he has come to by way of gospel music, and it shows, both in style and lyrical substance.

Of course, the song is peppered with the band’s signature religious language – there’s plenty of references to night and day, light and dark – all of which could have slid off a page of the Bible. Plus, Jesus is outright quoted in the second verse. It’s pretty obvious that the Biblical authors have their fingerprints all over this intriguing song.

But that’s still not what has caught my eye. Not quite.

Rather, it’s the message that this song is announcing, and where such a message might just derive from. Because, from the first line until its last, this song has but one message to proclaim: change, the redemptive kind, is at hand. Things are about to get better.

The chorus goes like this:

good people been down for so long

(Welcome to the revelation)and now it's like the sun is rising

(Welcome to the revelation)good people been down for so long

(Welcome to the revelation)and now I see the sun is rising

It is the inevitability of this change, which is emphasised over and over again, that has me so intrigued. This change, the details of which are masterfully omitted (meaning this song can exist as a hopeful meta-anthem, free from the confines of prescriptive context), is as unavoidable as the sunrise. This change cannot be hindered, just as the breaking of the dawn cannot be hindered. One can stare at the midnight sky, enveloped by darkness, and still know with complete assurance that the sun will return. Morning will come; it is a certainty, which is an incredibly rare thing.

Subsequently, this song isn’t a call to arms, Pharrell’s backing-vocal response to Marcus Mumford’s words is not ‘welcome to the revolution’, but ‘welcome to the revelation’. It is a call, not to make the change happen, but to witness it happen – pointing its audience not toward action, but toward hope. Hope in a redemption that is inevitable and a prevailing goodness that is written into the fabric of reality. It will come, it will be. And this subtle, yet salient, detail places this song in a very specific category of hopeful anthems. It sits with the likes of:

Sam Cooke, who in 1964, declared that:

‘it’s been a long time coming, but I know that a change is gonna’ come. Oh, yes it will.’

Or Lauryn Hill, who wrote in 1998 that,

‘everything is everything. What is meant to be, will be. After winter, must come spring. Change, it comes eventually’.

These songs, written in the middle of the night, speak of the coming dawn.

Which got me thinking, what taught us to do that? What taught us to believe that if it’s not good, it’s not the end? That if it’s not redeemed, it’s not over? What taught Sam Cooke, amid such injustice and violence, to have such a defiantly hope-filled message to declare? What taught Lauryn Hill to simultaneously lament over the struggles faced by black, inner-city, communities in America, and yet affirm that ‘after winter, must come spring’? And what has taught Mumford & Sons, and Pharrell Williams for that matter, to announce that after such a ‘long night’, they can see that 'the sun is rising’?

On what grounds can we possibly believe such a thing to be true?

It's a big question. Perhaps one of the biggest. And while I’m weary of declaring that I have the answer (at least, on anyone’s behalf but my own), I certainly have a theory. And I feel relatively confident putting it forward, considering his words pop up in the second verse of Good People.

My theory, perhaps unsurprisingly, is Jesus; the ‘light that shines in the darkness’, the one that we’re told darkness has not, and cannot, ‘overcome’. The one whose entrance into the world was, as the Biblical story goes, as preventable as the dawn (these themes sound familiar to you?). The one who, for thousands of years, has had communities of people looking into the darkness and declaring ‘I beg to differ’.

My theory is that Jesus taught us to believe redemption to be true. The things he did, the things he said, the things he fulfilled, but more than that – I think it is his death, and ultimately, his re-established life. I sense, in these songs, a hint toward the great story which underpins every other story. I hear the reverberations of Jesus’ resurrection in these lyrics.

I’m just not convinced that we’d be so sure that redemption will get the final say if something, or rather someone, hadn’t shown such to be the case. And so, I suppose what I'm ultimately suggesting is that any 'revelation' that this song intends to welcome us into has a distinctive flavour of Jesus about it.

I wonder whether Marcus, Ben, Ted and Pharrell would really believe that if something isn’t good, it isn’t over, had Jesus not taught them to.

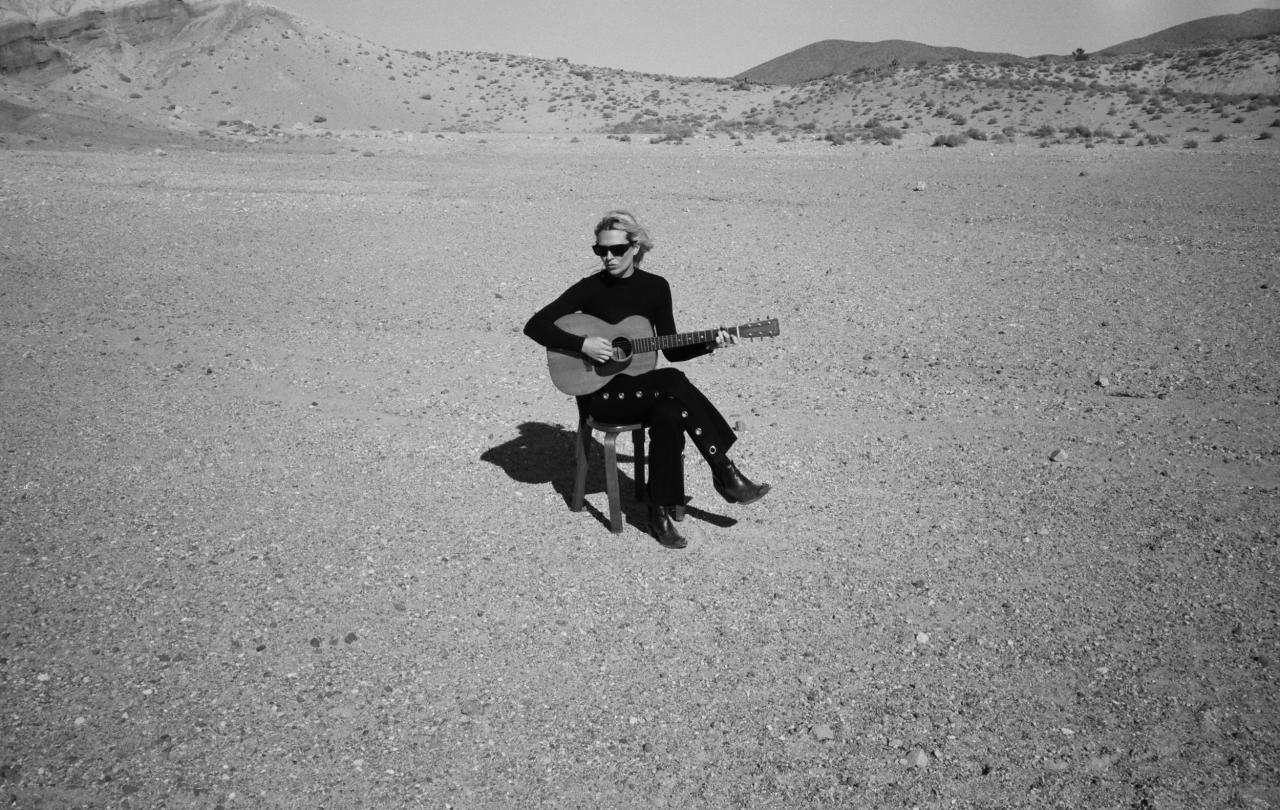

Watch Good People Live

Good People was first performed live at Pharrell Williams' Men’s Fall-Winter 2024 fashion show for Louis Vuitton. Williams is the creative director at the fashion house. Nativist Vocals perform first, followed by Williams and Mumford & Sons.