Do you like your photography cruel or kind? I’m generally an enthusiast for kindness – an unsung virtue – but I was mesmerised by a 2019 show of photography by Diane Arbus (1923–71) at the Heyward Gallery, London, and she’s the cruellest of the lot. Her photographs are a study in the awkward, the disturbing, and the unusual: a pair of brothers with extraordinarily large ears, a child with a grimace and a toy hand grenade, a boy from a pro-war parade, wearing with straw boater and “Bomb Hanoi” badge.

Arbus’s photographs have an undeniable charge. They hold your view. I’m glad, however, that I stand in front of her prints, not in front of her lens. She was not out to show you at your best. Here is Germaine Greer, describing a photoshoot with Arbus in the Chelsea Hotel in Manhattan.

'Clutching the camera she climbed on to the bed and straddled me, moving up until she was kneeling with a knee on both sides of my chest. She held the Rolleiflex at waist height with the lens right in my face. She bent her head to look through the viewfinder on top of the camera, and waited… as soon as I exhibited any signs of distress, she would have her picture… Nothing would happen for minutes on end, until I sighed, or frowned, and then the flash would pop. After an eternity she climbed off me, put the camera back in her bag and buggered off. A few weeks later she took an overdose of barbiturates and slit her wrists.'

Reviewing the Aperture monograph that would secure Arbus’s fame, Susan Sontag described her work as ‘a hymn to the isolation and atomization of the individual’. I am not sure that’s entirely fair. There was undeniable cruelty to Arbus. “You see someone on the street,” she wrote, “and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw.” Perhaps all photography risks cruelty, depicting us warts and all (at least before the advent of the Instagram filter, although I’m inclined to call Instagram filters the worst indignity of all). Yet, even in Arbus, just in portraying the human as human, compassion lurks at least just round the corner.

But sometimes compassion is nearer at hand, even centre stage. For that, I turn to Dorothea Lange (1895–1965), and to a recently-opened show of her work at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, entitled Seeing People. It holds Lange before us as the archetype of compassionate photography.

Lange could not have produced the photographs she did, however compassionate she might have been, without time, care, and attention.

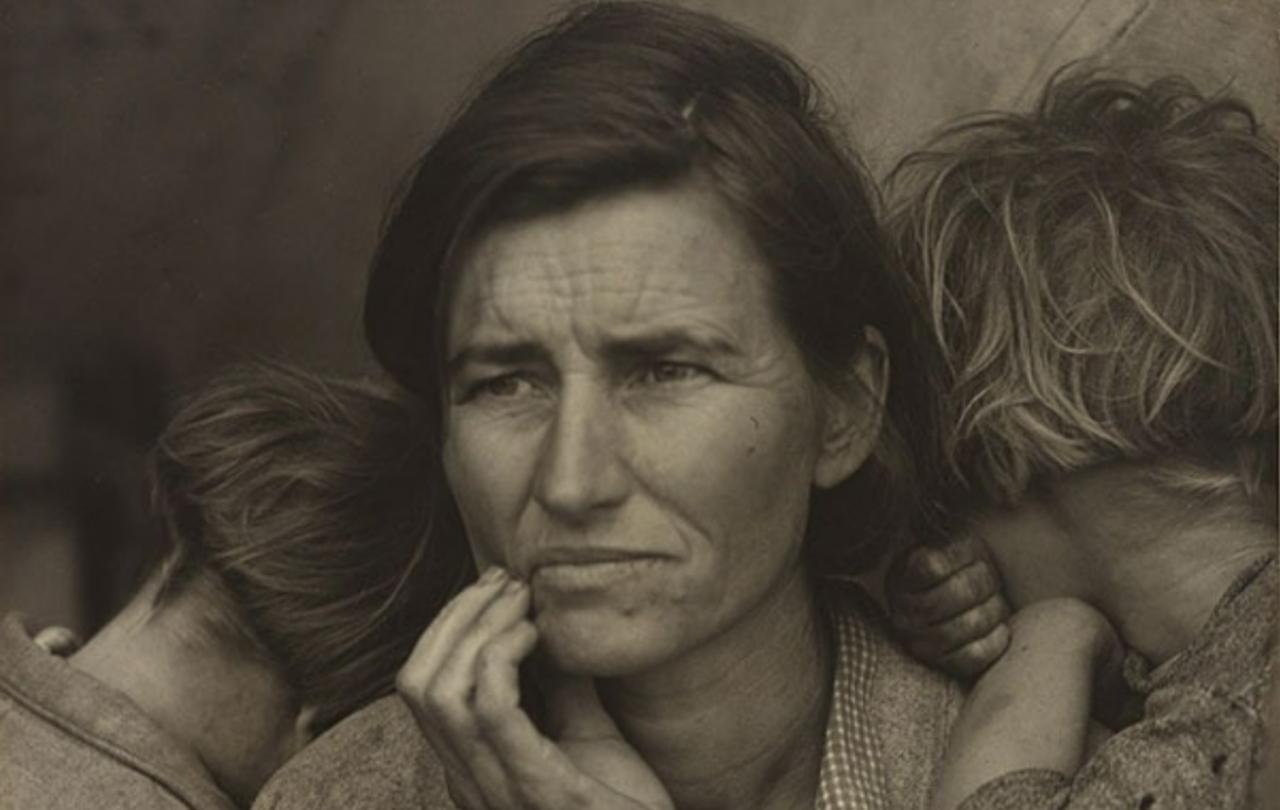

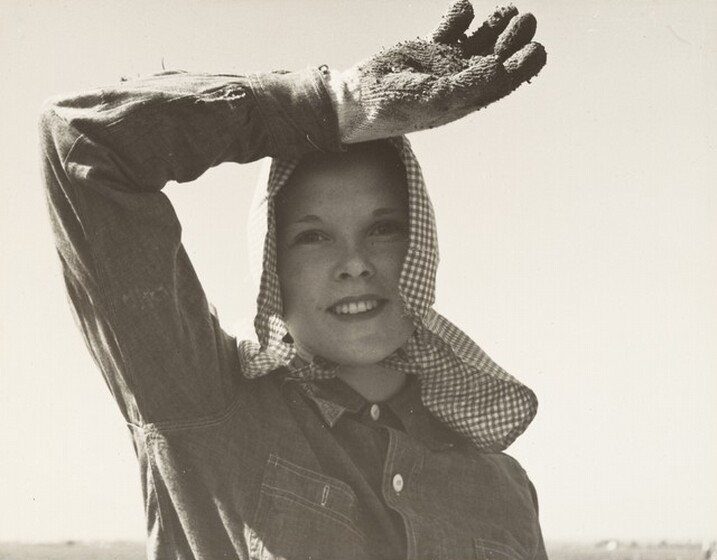

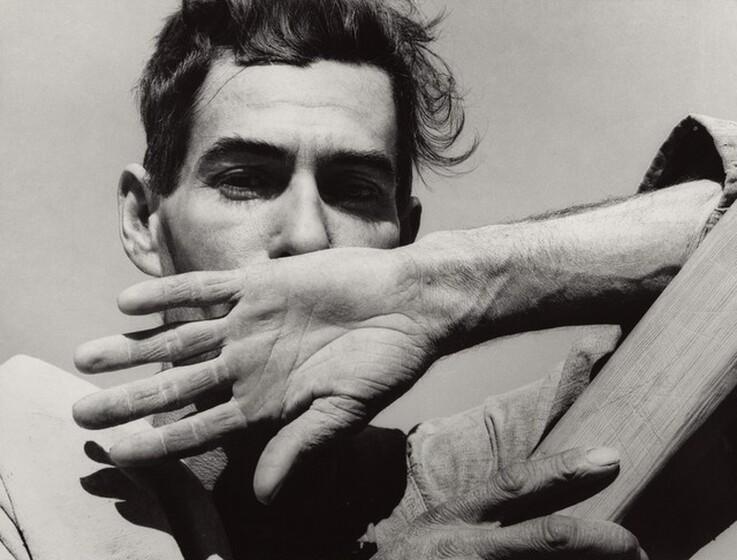

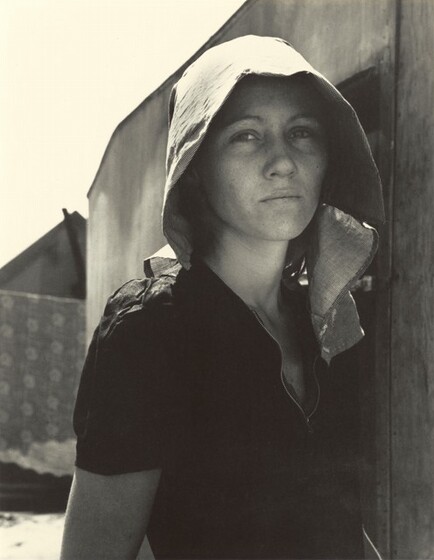

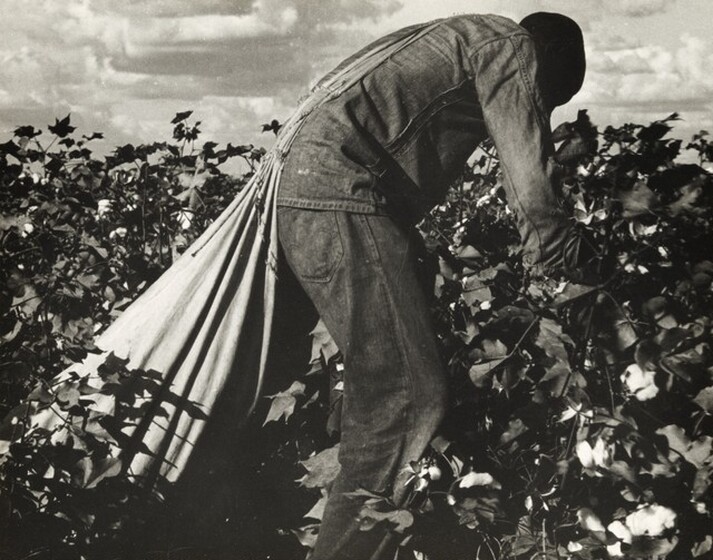

Lange trained as a portrait photographer, establishing a successful studio in San Francisco in the 1920s. Her approach to photography as a humane act developed during her work documenting rural poverty in the decade that followed. With it, she drew public attention to the effects of the Great Depression and the dust bowl, and helped to shift the public mood. From 1935, she did that under the auspices of what would soon become the Farm Security Administration. A photograph taken in March 1936 – “Human Erosion in California” (eventually known as “Migrant Mother”) – proved to be her career-defining shot. It shows Florence Owens, mother of ten children, photographed in the pea pickers’ camp in Nipomo, California. She and her family were in a dire situation, constantly moving to find new, transitory work.

In the 1940s, Lange documented the suffering of Japanese Americans during the Second World War (“Japanese American-Owned Grocery Store, March 1942”), not least once Japanese Americans began to be moved into internment camps (“Grandfather and Grandson of Japanese Ancestry at a War Relocation Authority Center, July 1942”). For the rest of her career, Lange would travel to places in the United States that rarely, if ever, feature in genteel conversation, to photograph people scraping through on very little, never failing to capture a sense of their dignity.

So, Lange was a compassionate photographer. I knew that before this show opened, and kindness is there in print after print. I was expecting that. What struck me for the first time is that Lange’s compassion was no light, easily achieved affair. She was careful, prepared, painstaking. She spent extended periods in deprived parts of her country, sometimes travelling for months at a time. She immersed herself in the life of a community, not least in its religious life, rather as an anthropologist would. She took detailed notes, and laboured over how to describe her subjects in captions and accompanying prose.

It is too easy to say that Lange was compassionate in way in which Arbus was not: too easy, if that implies that the fruits of her compassion were easily achieved. Lange could not have produced the photographs she did, however compassionate she might have been, without time, care, and attention.

She ‘saw people’, as the name of this exhibition reminds us. She saw people is because she took time to look. Before she clicked her shutter, she looked, she saw, she listened.

In contrast to Lange’s deliberate intent, Arbus was a wanderer. She had a remarkable eye, and she took what she wanted. She is among the greatest of opportunist photographers. Sontag got to the heart of that, remarking that Arbus treated human beings like the “found objects” that Surrealists elevated to the status of art:

What may seem journalistic (read “sensational”) in Arbus’s photographs places them, rather, in the main tradition of Surrealist art—with their taste for the grotesque, the proclaimed innocence with respect to their subjects, their claim that all subjects are merely objets trouvés.

Therein lies the difference from Lange.

The world could do with more compassion. Who would deny that? The message of the Washington exhibition, and of Lange’s work as a whole, is that compassion is not the work of a moment. Posting outrage to social media, or posting solidarity for that matter, is not going to change very much at all. It may make things worse. Lange’s lesson for this hour is that compassion requires us to take time. Her message is in her anthropological attention to people, communities, stories. She ‘saw people’, as the name of this exhibition reminds us. She saw people is because she took time to look. Before she clicked her shutter, she looked, she saw, she listened.

Dorothea Lange: Seeing People runs from 5 November 2023 to 31 March 2024 in the West Building of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Entry is free.