Update from September 2023:

It's been six months since I wrote this piece about a war that has been raging under our noses, hidden in plain sight. Six months since I spoke to people trapped in their cities, people cut off from their families, people scared for their lives.

Since then, the situation has only worsened. On the 19th of September, after ten months of blockading Nagorno-Karabakh (cutting off any access to Armenia), Azerbaijan launched an aggressive attack on the enclave. Calling it an 'anti-terror' operation, 60,000 Azerbaijani soldiers have forcefully taken control of main roads, villages, and major cities. This is a major offensive against a region with a population of only 120,000. 27 people, including civilians, are reported to have been killed in the past twelve hours alone. And with Azerbaijan declaring that it will not retreat without complete surrender from the Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh, the violence is unlikely to cease in the near future.

This is a humanitarian crisis; one which deserves our full attention. The piece below was originally written in March 2023, it provides the long and complex context for what is currently happening in Nagorno-Karabakh - the war which can no longer remain invisible.

The war that we're not seeing

In the landlocked region of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh in Armenian), peace has not yet had the final say.

Since the 12th of December 2022, the Lachin Corridor (referred to by Armenian inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh as the ‘Road to Life’) has been blocked, and the 120,000 people who call the 4,000 square km enclave home have been effectively trapped. This corridor is the only physical link that Nagorno-Karabakh, which is internationally recognised as territory of Azerbaijan, has to Armenia. Subsequently, the trauma of this essential road being obstructed is twofold:

Firstly, the very nature of this blockade means that there is a dangerous shortage of food, medication and other every-day essentials being brought into the region. Speaking to a Priest who is among those currently trapped in Nagorno-Karabakh, he described what he is experiencing as a humanitarian disaster, he explained ‘I am witnessing the stripping away of my community’s human rights’.

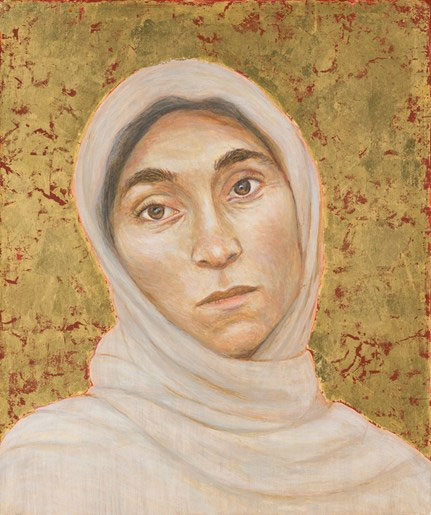

Secondly, the people of Nagorno-Karabakh are experiencing the trauma of being disconnected from friends, from family, and from their sense of self, as almost the entire population identify as Armenian. To fully appreciate the situation that the small region currently finds itself in, it is necessary to zoom out of the detail of the current blockade and briefly take a wider view of historic relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The context of conflict

The blockade of the Lachin Corridor is the latest incident in what has been a complex and enduring conflict between the neighbouring countries. Since the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the re-mapping of territorial boundaries throughout the twentieth century, the countries have fought over the legal governance of Nagorno-Karabakh. The 21st century has therefore been characterised by both recurring attempts at reconciliation and episodic clashes. This culminated in a short but devastating war in 2020, resulting in Armenia being forced to relinquish any military control over the region.

The Armenian people of Nagorno-Karabakh have not moved, and yet the entirety of their ethnic identity has been frequently altered. Their home has been absorbed by a neighbouring region, and conflict has been a constant reality.

While both Azerbaijan and Russia are determined that the people of Nagorno-Karabakh are being kept safe and well, it seems that such an insistence isn’t quite translating into action. As one interviewee put it,

‘Azerbaijan won the war, now they need to win the peace’.

The immediate vulnerability of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh cannot be overstated; as is being exemplified by the severe destabilisation that the blockade of the Lachin Corridor is causing.

A faith that is targeted

This is, undoubtedly, an ethnic and political conflict. It is the residue of the re-drawing of territorial lines and the legacy of a fragile form of peace. Local leaders stress that it is not primarily driven by religion. They are critical of foreign commentators who position it as such.

What is not being understood, even still, is the way that religion is being targeted, weaponised even, within this ethnic and political conflict. Religious aspects being either sensationalised or ignored by the global media. It serves one well to be wary of one-dimensional interpretations of this conflict, this includes narratives that reduce it to a quarrel between two world religions. However, it is equally unhelpful to ignore the way in which the people of Nagorno-Karabakh's sense of self is being tactically targeted. This includes their profoundly Christian heritage.

On October 8th, 2020, the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral in the city of Shushi was shelled by Azerbaijani forces. It was struck not once, but twice, within the space of only a couple of hours. Despite Azerbaijan’s insistence that the Cathedral was not their intended target, the Armenian Ministry of Défense remain resolute that the destruction of their cathedral was intentional. Having had Nagorno-Karabakh on his radar for many years, it was the footage of the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral in ruins that caught the attention of Rt. Revd Dr Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop of Coventry. Filming a message from the ruins of Coventry cathedral, which was largely destroyed by German bombs as part of the Coventry blitz during WWII, Bishop Christopher wanted to let Armenian Christians know that they weren’t unseen, nor were they alone.

From Coventry to Nagorno-Karabakh

Subsequently, Bishop Christopher has become a long-standing advocate and ally for the people of Nagorno-Karabakh, having visited the region on numerous occasions, including with a parliamentary group in 2022. When asked about the instrumentalization of religion within the ongoing conflict, Bishop Christopher observed that:

‘if you want to get at people’s identity, you get at their religion. If you want to destroy their identity, you destroy their religious symbols’.

And this is arguably what is being seen in Nagorno-Karabakh, a Christian enclave that, according to tradition, traces its Christian roots back to the first century AD.

To intentionally target sites of religious and/or cultural importance has long been considered an international war crime. This is largely because of the profound and lasting effect it has upon those who accredit a sense of belonging to such places – such an obliteration strikes at the heart of their sense of self. And yet, according to reports, the 2020 destruction of the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral (intentional or otherwise) is by no means anomalous.

The seemingly systemic disappearance of religious and cultural sites of significance in Nagorno-Karabakh has led researchers and reporters to interpret what is happening in the region as a 'pattern of total cultural erasure' and communicate their fears of the eventual disappearance of Nagorno-Karabakh as a self-identified Christian enclave.

A faith that is responding

Ironically, the people’s Christian faith, and the hope that it offers, is one of the only things that has not, and cannot, be stripped away.

Despite the immense pressures being placed upon the residents of Nagorno-Karabakh, Bishop Hovakim Manukyan, Primate of the Armenian Churches of the United Kingdom, is assured that ‘the people’s faith is stronger than ever’ and that it ‘has not, and will not, ever be abandoned’.

Speaking once again from within the currently entrapped region, a local priest tells of how church attendance and a sense of spiritual unity is particularly strong. Is seems that this is partly because the residents of Nagorno-Karabakh don’t believe they are receiving the help they require from their global neighbours, making God their most tangible solution. This is also, in part, a rebellious dedication to their faith. It is people holding onto a Christian identity in defiance of any attempted erasure of it.

This is not unusual. Interestingly, it is in places where the possession of Christian faith can bring forth difficulty, discrimination, and even danger, that it sees its most rapid growth. As is exemplified in various countries, both historically and in the present day, a dangerous faith simply does not equate to a disappearing one.

A faith that can reconcile?

Is reconciliation between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and ultimate peace Nagorno-Karabakh, possible? This was my final question posed to both the Bishop of Armenian churches in the UK and the Bishop of Coventry, a city which has affectionately been entitled the City of Peace and Reconciliation (due to its response to the afore mentioned Coventry-blitz).

Bishop Christopher of Coventry was profoundly hopeful that reconciliation is possible. After all, this is by no means an ancient conflict. However, the process of reconciliation will undoubtedly be long and complex and must begin with an immediate cease in the ‘nurturing of hate’.

Bishop Hovakim also shared his hopes for reconciliation, that although reconciling the deep divisions will undoubtedly be ‘challenging and painful’, it is by no means impossible. He places emphasis, not on the moments of intense conflict, but on the times where Armenia and Azerbaijan have been neighbours ‘living side-by-side' and ‘sharing so much’.

Surely, just and lasting peace can only be possible when the people of Nagorno-Karabakh are re-afforded their safety, their security, and their fundamental human rights. Considering that possession of one’s own identity has long been considered one such human right, the reinstatement and reparation of the Christian heritage and identity of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh must surely be an essential ingredient in any reconciliation.